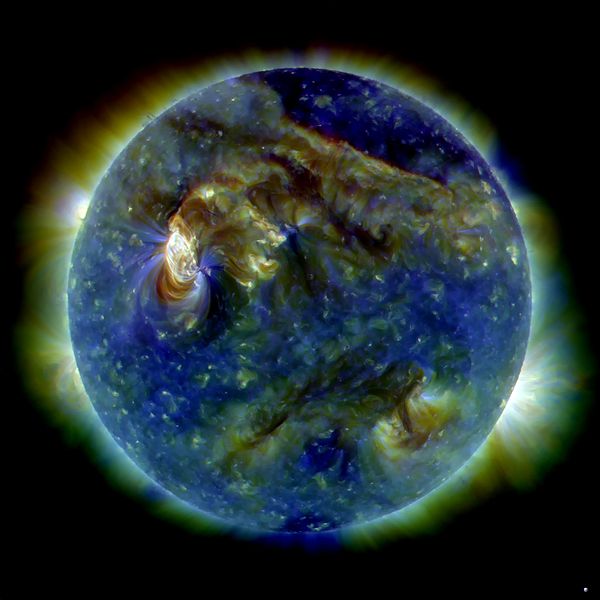

Plasma Science and Fusion Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in

Cambridge, Massachusetts (Image from the MIT website)

***

I had a good time this evening delivering a private lecture as part of the Cruise Lady “Learn Our Religion” series up in West Jordan. I gave it the title “Prelude to the Reformation,” but it was the first half of a two-part presentation on Martin Luther. In the lecture tonight — which, I think, is eventually supposed to be posted online somewhere, though behind a pay wall — I concentrated on the religious and political conditions that led up to the Lutheran Reformation. I brought to a close — cliffhanger style, I hope! — with Luther’s affixing his famous “95 Theses” to the door of the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517.

***

Also, some new items have recently been posted on the website of the Interpreter Foundation, and I’m a bit delinquent in calling them to your notice. Here are three links:

Audio Roundtable: Come, Follow Me Old Testament Lesson 11 “The Lord Was with Joseph”: Genesis 37–41

***

I’ve said before that there is a religious dimension — not the most important, certainly, but also not inconsequential — to the Russian invasion of Ukraine:

“Holy wars: How a cathedral of guns and glory symbolizes Putin’s Russia”

“Putin’s claim to rid Ukraine of Nazis is especially absurd given its history”

“Plug-In: Why some experts insist Vladimir Putin is motivated by history and religion”

A thoughtful Latter-day Saint student of warfare and military history has written an article that many of you might find of interest:

***

I was sorry to learn this afternoon that Phyllis Nibley, the widow of Hugh Nibley, passed away on Saturday. I’m afraid that I hadn’t seen or spoken with her for a very long time. Curiously, though, I found myself thinking of her on Saturday, wondering how she was doing or even whether I might have missed news of her death. This note, from her daughter Rebecca, was passed on to me today:

My mother passed away peacefully just after I finished reading to her from third Nephi. It was 4:58 AM when she took her last breath. The funeral will be held on Saturday March 11 at the Edgemont 2nd ward at 11 AM. I think there is also a viewing the evening before I will let you know the details later.

***

Dr. Ian H. Hutchinson is Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), with a primary research interest in plasma physics. In these passages from his book Monopolizing Knowledge (Belmont, MA: Fias Publishing, 2011(, 1-3), he takes aim at “reductionism”:

It is the assertion, or more usually unspoken presumption, that when a satisfactory scientific explanation at a reduced level exists, such an explanation trumps, invalidates, or explains away understanding at higher levels: that the higher level descriptions lose their force or relevance. This is certainly what, for example, Donald MacKay in his The clockwork image (1974) is complaining about, and why he coined the disparaging but descriptive phrase “nothing-buttery” to refer to ontological reductionism. “Nothing-buttery is characterized by the notion that by reducing any phenomenon to its components you not only explain it, but explain it away.” It is definitely helpful to analyze animal bodies in terms of their cells, but it is unhelpful, and fundamentally untrue, to conclude that if one completes such an analysis, then animals are demonstrated to be nothing but assemblies of cells. The presumption that reduced level explanations explain away higher level descriptions generally operates inconsistently. It must do so, because science is full of descriptions and explanations that are actually not reductionist in the senses identified by [Richard] Dawkins and [Michael] Ruse. Nothing-buttery usually operates in such a way as to discriminate against the descriptions that don’t conform to the ideals of science. We shall examine later some examples of this process at work, but here we simply draw attention to the fact that it is a trait of scientism. (1-3)

Repudiation of scientism is the only way the we can break free from some of the more debilitating habits of thought that have dominated modern intellectual life. But this repudiation is unsustainable, even by the most heroic effort, without a distinction between science and scientism. If denying scientism’s sway requires us to deny the truthfulness, value, or reality of scientific knowledge — as seems to be implied by some of today’s critiques — then in my opinion the move will fail. And it should fail, because in fact science does give real, reliable, knowledge. It is just that science and scientism are not the same thing. Science is not all the knowledge there is. (4)

Illustrative specimens that come to mind might include, among almost infinitely many others, any painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Nobody, I trust, would seriously propose that one had really thoroughly understood his “fresco” of The Last Supper by measuring it precisely, calculating the chemical composition of the various pigments, determining their depth on the wall, and so forth, while excluding Leonardo’s purpose in creating it and in making it just as it is, the historical background of the painting (including the New Testament story that it represents), the intentions of those who commissioned it, its function in the room of Milan’s Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie where it appears, the function of that room itself, the economy of late-fifteenth-century Florence, and a host of other potentially fruitful approaches.

If one could somehow construct an exhaustive and accurate account of the synaptic firings in Shakespeare’s brain (or the Earl of Oxford’s, or whatever author you prefer) during the time that he was writing King Lear, would doing so actually help very much, if at all, in fully understanding or appreciating that very great play?

***

Finally, here’s something terrifying that you might have missed. It’s from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File©. To be forewarned is to be forearmed:

“What do students’ beliefs about God have to do with grades and going to college?”