For some reason, I have recently received a few messages from readers interested in where I stand in relationship to the “Minimalist vs. Maximalist” debate. For those not familiar with this term, the so-called “Minimalist vs. Maximalist” debates refer to discussions that occurred some twenty to thirty years ago in biblical studies.

To answer the question, like all mainstream scholars, I don’t fit into either group. While we will always continue to debate issues concerning Israel’s past, the truth is that contemporary biblical scholarship has surpassed the specific concerns that once characterized the Minimalist and Maximalists discussions of the 1990’s.

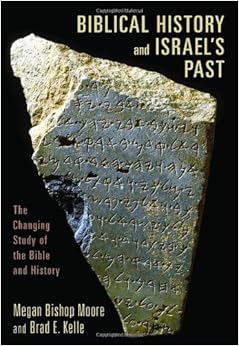

Perhaps the best way to summarize the matter is to cite Megan Bishop Moore and Brad E. Kelle’s recent assessment of the matter in their work, Biblical History and Israel’s Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History published in 2011 by Eerdman’s. The authors explain:

“The study of Israel’s past has moved beyond the minimalist-maximalist debate. Lester Grabbe’s Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? (2007), Victor Matthew’s Studying the Ancient Israelites: A Guide to Sources and Methods (2007), and Hans Barstad’s History and the Hebrew Bible (2008) are books that are, in effect, modern prolegomena to Israel’s history. Rather than write histories of Israel, Grabbe, Matthews, and Barstad put evidence for ancient Israel and issues about how to interpret it in front of the reader. Other recent histories, such as K.L. Noll’s Canaan and Israel in Antiquity (2001), reflect 1990’s concerns and attempt to include ancient Israel in a broader geographical and chronological span than twelfth-century-to-third-century central hill country Palestine. Recently, Mario Liverani has offered a history of Israel that neither fully adopts what he calls the traditional format, which, in his opinion, does not understand the biblical sources fully in their context (which he sees as the Persian period), nor entirely endorses minimalist ideas, which, he says, do not recognize the importance of the ancient material that the biblical authors used. Meanwhile, the study of Israel’s past outside of the formal disciple of history, especially through archeology, has continued.” (p. 39).

So like all mainstream scholars today, even though I feel sincerely grateful for the earlier academic discussions of our predecessors, I don’t find myself in either of these two camps. Contemporary studies have matured beyond these debates in the 1990’s.

It’s an exciting time!