As part of the Patheos Passing on the Faith conversation, I decided to invite my friend Stephen Ingram to share his thoughts. Stephen is a seasoned youth minister, an author, and a really thoughtful person. I was lucky enough to attend college with him and am honored to offer his thoughts on how we pass on our faith to the next generations. Pick up his book, Hollow Faith, or visit his Web site, Organic Student Ministry. Like today.

****

We would sit around the kitchen table. It was a modest table, worn from plates and elbows sliding across its surface, that had been in that house for decades. I would sit and listen; he would talk. My grandfather, Paw Paw George, would tell me stories, and I would work my hardest to memorize them. I tried to memorize them, so that I too could tell them one day. I memorized them so that when his body no longer possessed life, he would continue to live among us, through me. I knew he had cancer, I knew his days were limited and I knew there was nothing I could do to fix him. I wanted to soak as much of him in as I could so that after he was gone, there was a part of him I could still hold on to.

I never asked about the geography of the story, or tried to validate the facts with secondary and tertiary sources. I did not check World War II records and I did not check his genealogical account for accuracy. I simply basked in the story and let it shape me and form me. His stories provided a narrative and a back-story to the story that I would live and the stories that I would tell.

Stories tell us things that facts cannot understand.

When I was in Israel recently, I was reminded of the power of story. Every practicing Jewish child knows their story. They have been immersed in it since before they could understand it and have been taught it before they could remember it.

It is their narrative; it shapes them and forms them. Their year is shaped by the story and their days numbered by its telling and retelling. They are people of the story. We, Western Christians, have forgotten our story, and most of our children have never heard it. We have replaced the stories with relevant and topical interpretations of the story and have prescribed life applications to each that, we believe, will provide a more rounded character. We have assigned platitudes and placard worthy lessons to these gritty stories and have forgotten that the story was meant to shape us, instead of us shaping the story.

And now we are stuck with an idealized shell of a story whose rough edges have been smoothed and whose scope and meaning spreads as far as our current context will allow. We have created a frail version of our narrative that has been crippled by relevance driven self-help.

Our medicine is poisoning us.

In youth ministry the story is more important than it has ever been. We are not only guilty of diluting the narrative of faith, but we also squelch the story that God is still telling in our lives. Our proclivity to an upfront, expert driven model of preaching robs our congregations and students of their place in the story. When we practice this, we work from the assumption that there is a singular narrative and deprive the rest of our group and ourselves of the many strains that make up the rope of our faith. I believe there are three practices we can perpetuate that will allow the story to breathe new life into our dry bones:

1. Tell the raw, un-contextualized, problematic story and let it sit. We work really hard to contextualized and fix the story or pretend that it is not problematic. Let the story make our students uneasy. Do not solve it for them. Help them see the beauty of a story that is not wrapped up neatly with a bow. Challenge their presumptions and do not allow them to take an easy way out. Force them into a midnight wrestling match with the narrative and watch them never walk the same again.

2. Let the story shape us and form us. I love the Jewish calendar. You cannot go a year in the Jewish calendar and not hear your story. Yes, we have the liturgical calendar and the lectionary, but it does not shape us and provide the narrative as fully as the more inductive Jewish calendar year. I believe this is because the Lectionary and the Liturgical calendar are perpetuated within the walls of the church, while the Jewish calendar is perpetuated from within the home. When our children grow up hearing the stories and celebrating the stories in their home, then we will understand what it means to be shaped by the story. One old Jewish scholar taught me that when the Jews read the Torah aloud it is always read in first-person present because the story in those pages is their story personally and they own it currently.

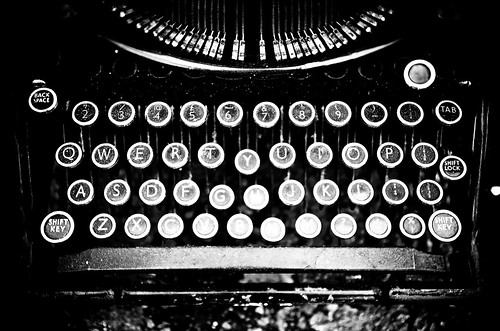

3. We must teach our children to be poets and storytellers. I am deeply in love with Garrison Keillor. I want him to adopt me as his grandson. He tells his stories from Lake Wobegon and they become our stories. Everyone who listens to them finds themselves in those stories and for a couple of hours on a Saturday night we all have a common narrative. Our children must understand that the story must shape them but it can only continue if it continues through them. It is not a closed canon. They — we — are writing on its pages everyday. They have to understand and be given the opportunity to own it and then interpret their lives through it. They have to be given the impetus and the courage to continue writing and telling the story of our faith.

My grandfather has been dead for eight years now. While he is now dust, there are two things that I hold dear from him. On the day we buried Paw Paw I took a jar and collected the dirt that would cover him. It sits in my house as a connection point between where I live and where he is buried. My other possession is his stories. They live in me now. They are not for me to keep and covet; they are there for me to give away to my children. His stories, and hopefully my stories, will continue through my children and grandchildren.

Our collective story of faith can only survive in the same way.

________

Stephen’s Bio: I am a dad, husband, and foodie. I have the joy of serving as the Director of Student Ministries at Canterbury United Methodist Church in Birmingham, Ala. I have a BA in Religion from Samford University and a Masters of Divinity from McAfee School of Theology in Atlanta. I have worked as a student minister for over 13 years and also serve as a lead consultant with Youth Ministry Architects. I live in Birmingham with my wife Mary Liz and our three kids Mary Clare, Patrick, and Nora Grace.

My book Hollow Faith: How Andy Griffith, Facebook and the American Dream Neutered the Gospel is available from CYMT Press and at on Amazon.com.