Jeremiah 23:23-29 + Hebrews 11:29-12:2 + Luke 12:49-56

Jeremiah 23:23-29 + Hebrews 11:29-12:2 + Luke 12:49-56

As the father of two young sons, I can’t say that I’m thrilled with today’s gospel text, much less to have to preach on it and reflect on it all week long. Quite frankly, in ways both large and small, there’s enough division in the world right now without Jesus adding anything to it.

In my family, for example, we’re frequently divided about even the tiniest of things. Like how much screen time is too much?

Or how many pieces of broccoli do you need to eat and does the number of broccoli pieces then correspond to the number of ice cream scoops you get to eat for dessert?

Or how much stuff can remain on the floor and a room still be considered clean? And related to it, that age-old question of exactly how many Legos can fit on a bedroom floor?

If Jesus considers divisiveness within the world and within families something new he’s bringing to the table, then he’s clearly never gone on a cross-country road trip – or even just 15-minute drive to church – and attempted to figure out just where one child’s side of the van begins and the other child’s side ends.

Perhaps you’re hearing Jesus talk about division in families and this week you’ve had one of those fights with your spouse or significant other that was so critically important that you can’t even remember what it was about 10 minutes after you storm off to separate rooms to calm down.

Division is everywhere in our world, and often there’s a lot more at stake than dessert and clean rooms. We’re divided in painful ways, sometimes in our families, frequently in our churches, and constantly in our country. We’re divided in serious ways, along racial and ethnic lines, along socioeconomic lines, and, in the hyperpartisan environment of an election year, most definitely along political lines.

And Jesus says he comes not to bring peace but division? If you’re like me, there’s a part of me that wants throw up your hands in exasperation and say, “If that’s the good news for our world, why even bother? We’re quite good at division all by ourselves. We’re experts at it.”

Of course Jesus was no stranger to division. Jesus isn’t teaching in the midst of a people who are happily united, working in harmony for the good of humanity. He was living in an occupied country. His world was a deeply divided as our own.

So, it got me to thinking this week about what it means for Jesus to bring division to an already deeply divided world. Think about the world in which Jesus lived. Like our own time, there were all kinds of strident religious and political divisions between the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots. Like us, there was social and ethnic division between, the Jewish people and the Samaritans and other gentiles. You had despised or feared outcasts, too, like tax collectors working for the occupying Roman Empire, the local drunks at the bar, and the prostitutes and beggars on the street.

But these divisions also brought a kind of order and structure to society. These divisions oriented and organized people. They helped them know who was friend and who was foe, who was the ‘us’ and who was the ‘them,’ who God loved and who God rejected. However these divisions started, whether innocently or maliciously, over the years, they eventually developed into ingrained prejudice and even hate. They became rooted in fear, teaching generation after generation to distrust and dislike those with different beliefs, different life circumstances, and from different ethnic backgrounds.

But when you boil down and simplify a lot of our ingrained divisions – even silly ones about vegetables and clean rooms – it often comes down to fear. We fear sickness so we have to eat our vegetables. We fear chaos or the embarrassment of a friend dropping by a dirty house, so we have to clean our rooms.

And when we fear, humanity tends to seek out power for safety and comfort. We seek control over the chaos of life by creating evermore rigid boundaries of who’s in and who’s out. We seek our own security, even if it’s at the expense of others.

If it sounds familiar, it should. Today we call these wedge issues and partisan politics. And this kind of fear-based division is easily manipulated and exploited by those in cynical pursuit of power and influence.

But that’s not the kind of division Jesus is talking about today. In fact, the division of Christ takes direct aim at these human divisions by attempting to reorient our identity away from the tribalism of families and extended families and toward a broader understanding of who our family really is.

A few chapters earlier in Luke, Jesus explains that his mother and brothers aren’t his true family. Instead, he gathers together a family as big and diverse as humanity. They were the prostitutes and drunks, the Roman centurions and high-ranking Jewish officials, the smelly fishermen and the odious tax collectors.

People who should have been divided by the world became a family, and that kind of boundary-crossing love was so divisive itself that Jesus was eventually crucified for it.

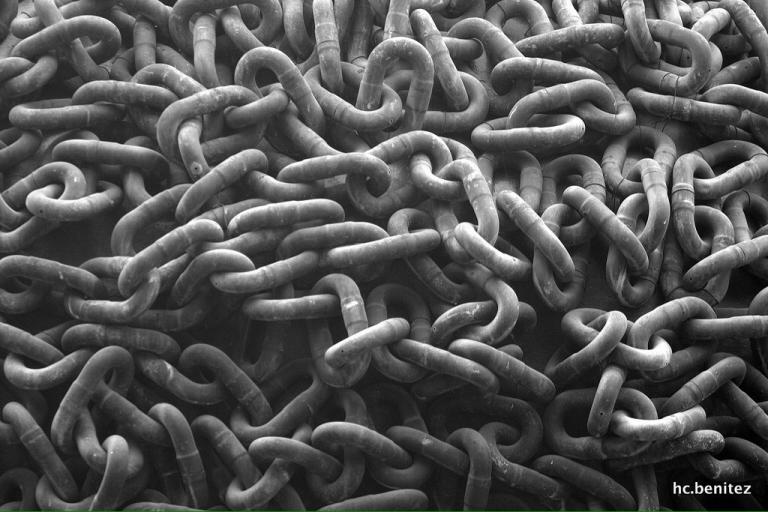

This divisive love of Christ disrupts the divisive fear of the world, and his unrelenting and unconditional love for all falls like a sword across the neat and tidy divisions that order the world. His love is like a hammer breaking into pieces the rocky walls that separate us.

Jesus’ answer to the division in our world isn’t to offer simple unity without conflict or difference. It isn’t to gather us around a campfire and dole out warm fuzzies. It’s to cut right into the heart of our divisions and to baptize us in the fires of love, a bold love that divides us precisely because it dares to confront our divisions with the proclamation that no matter what group we belong to, we all belong to God and to each other.

Now it might sound nice and sweet in the pulpit, but it is dangerous, disruptive work in the world and in our own internal life. It forces us to confront the ways in which we too have feared or demonized the beloved other and deepened the fractures in God’s diverse family.

If we do this internal work and then go out into the world to proclaim it and live it and we, too, will be considered divisive, maybe even a threat.

So maybe instead of hearing in Jesus’ words today echoes of divisive fear-based politics or of humanity’s backseat squabbles about whose space belongs to whom, I want us to hear in them the life of Jonathan Myrick Daniels, who died in southern Alabama on this day, 51 years ago, and who very much embodied the divisive love of God in the last months of his life. A 26-year-old seminarian studying for the priesthood in Massachusetts, Daniels answered Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s call in March of 1965 for clergy to march in Selma, and he then returned during his summer break to continue to work in the Civil Rights Movement.

But on a hot summer day in Lowndes County, after he and other Civil Rights activists were released from prison following a protest, Daniels walked with three others to nearby Varner’s Cash Store to buy a cold soft drink. However, a deputy named Tom Coleman wouldn’t let them into convenience store because they were black people in their group. Coleman then leveled his shotgun at a 17-year-old black woman named Ruby Sales, but Daniels pulled Sales out of the way, threw himself in front of the blast, and was killed instead.

Now, with hindsight, we certainly wouldn’t call Daniels a divisive figure; we’d call him an inspirational one, a holy one even. In fact, the Episcopal Church officially honors him today as a martyr, and each year the diocese of Alabama hosts a massive racial justice pilgrimage to the site of his death.

But at the time, Jonathan Myrick Daniels was divisive. His faith made him divisive. His love made him divisive. His willingness to stand up to the oppressive racial division in society made him divisive. So divisive it got him killed.

Christian tradition is with a great cloud of witnesses whose love for others was so boundary-breaking, so selfless, and so relentless, it was divisive for its time. Today, however, we consider them saints and luminaries of the faith.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Dorothy Day, Archbishop Oscar Romero, and the dozens of other martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement were all divisive.

Thanks be to God for love faithful enough to be divisive.

So the question then is not whether the world is divided. There has always been division in the world. The question is how we will divide the world. Will we divide the world with fear, in the pursuit of power and control through demonizing others? Or will we divide the world in the courageous proclamation of unrelenting and unconditional belovedness of all in God?

Let us divide the world with love. May the sword of God’s unconditional belovedness pierce us, carve up our divisions, and breaks us apart so that we might begin to pick up the pieces of our already fractured lives and communities.

Perhaps then we might grasp how deeply connected we are so much so that if I ever want to proclaim my belovedness I can only do so if I proclaim yours as well, my neighbor’s belovedness as well as my enemy’s.

So let us give thanks that the love of God is big enough not just to handle division but to spark it, so that the deep divisions in our world might be consumed in the fires of God’s holy love, until all that remains is love.

Image Credit: “maths” by Back on the Bus, used under Creative Commons

Works Referenced/Further Reading: Barbara Brown Taylor, “Family Values,” in Gospel Medicine.