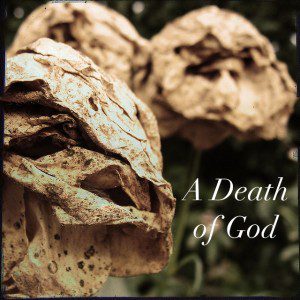

Over the next week, I will be posting a three-part essay on the death of God, my experience of it, and my search for meaning through it. I invite you to walk with me and dialogue with me. Part one, the Foolish Death of God, can be found here.

In the 1960s, the notion of the death of God was popularized by Thomas J.J. Altizer, who suggested that on the cross, God died and, through this death, became immanent, breaking the barrier between the sacred and the profane. For Altizer, this death was an historical event that happened “in our time, in our history, in our existence.”

What he put forward was a totalizing theory that meant that the transcendent God died forever and at a clear point in history, the cross. It was the death of God as “Other.” While there is much I love about Altizer’s work and much with which I identify, I’m not sure I can agree with his assertions completely, for the God I have experienced was a very real, very alive kind of God, very much my Beloved, very much transcendent as well as immanent. Altizer’s theory also seems a clever dodge to affirm the death of God without having to face the full force of God’s death as a person of faith.

And, I suppose, this is the point I’m making. That the death of God, for persons of faith, is ultimately and excruciatingly a personal event, just like any death of a beloved; no amount of theological explanation can change that experience into something redemptive. It is transformational, to be sure, for the death of God becomes a watershed marker in the life of a Christian, a point from which the spiritual life can never again be the same. But something good?

When I experienced the death of God, though I didn’t have the words for to understand it at the time, I began to travel through the stages of grief, sweeping into and out of the stages for weeks, months, even years. And I still do grieve at times, though the urgency of the emotion is blunted now. At the time, however, what I believed I was grieving and suffering through was my own loss of faith, my own failure as a Christian. I thought that the death of God was somehow my fault, my undoing that expelled me from the ranks of acceptable Christians. No small wonder, I kept much of this buried deeply within. I blamed myself for a death that was out of my control, unconsciously channeling Nietzsche who said that God was dead and we were his murderers.

Sometimes, though, death is simply death, and no one is to blame.

I wish someone had told me then what I know now: that what I was experiencing — the death of God — was profoundly spiritual and profoundly Christian.

If only someone had told me that this too was part of what it meant to be a Christian.

Our faith tradition affirms the death of God, in both its narrative, its saints’ and holy persons’ lives, in its liturgical calendar. I think of the Jesus’ own cry of God-forsakenness on the cross. I remember the full tomb of Holy Saturday, and the men who carried the body of God’s Incarnation to the grave. I think of myriad saints and theologians for whom the death of God permanently marked their souls, and transformed them into something more beautiful and heartbreaking than we could conceive. St. John of the Cross and his dark night of the soul; Mother Teresa who, for almost the entirety of her remarkable work in Calcutta, wrestled privately with the death of God, the loss of God’s voice, her faith, spirit; St. Vincent de Paul’s (whitewashed) struggles with doubt and unbelief.

In my own tradition, Barbara Brown Taylor has written powerfully and pastorally about the Absence of God in her book Gospel Medicine. She casts the Ascension in such a light, writing that it was the moment in which the Lord for whom the disciples had given everything, at last and forever, left them behind. And, this is a feast we celebrate as holy in our liturgical calendars, this holy feast of Absence.

In the Christian life, many writers and theologians seem to prefer this metaphor of absence to that of death. This experience has been likened to the desert, the wilderness, the darkness; or downplayed as spiritual dryness, the silence of God, or a refining test of one’s faith to see how deep one’s faith is rooted in the soil. Psychologist James Fowler would likely refer to it as the Individuative-Reflective stage of faith as a way to explain it.

But when I read the unresolved prayers of Mother Teresa, the ache of Taylor’s writing on the subject and reflect on my own experiences and those others have shard with me, these metaphors all seem somehow too soft for the overwhelming grief and emotional turbulence of the experience. It is too gentle a metaphor for what the soul experiences and how profoundly it changes the spiritual life.

Death, for me, is the only approximation that fits.

Indeed, the fundamental narrative of the Christian tradition, the turbulent, emotional Passion of Holy Week centers on the death of God, incarnated in Jesus. God experiences death. In the formulation of that week, God in Christ serves on Maundy Thursday, dies on Good Friday, remains dead on Holy Saturday and is resurrected on Easter.

In liturgical life, we relieve these experiences during Holy Week, so though we can say that Christ died once for all, Christ also dies always. We reenact and relieve them through our liturgical life. We re-member them.

This carries over into our spiritual lives, as well. To be a Christian and not experiences the death of God is to miss a fundamental, constitutive piece of the tradition. It is ingrained in us through the deep, powerful stories of our faith, that God had a body and that body died. God has died.

And while we know this story is real and true, we also know that those stories speak to us metaphorically and mythically. This story becomes an archetype for our spiritual lives. Such an archetype, of a God who dies, shapes how we experience spirituality, why we experience it the way we do and what it means. And if we are not experiencing the death of God, then we are not experiencing the God revealed in Christ, both the God Incarnate who dies and the God who stands silent as death, absent as the dead, when Christ cries out in forsakenness.

To be Christian is to experience the death of God, and to experience it not as a negative, or as a punishment, or as a failure, but as a transformation, as a paradigm shift of who and what God is and can be. The temptation, of course, is to attempt to classify this death as good, as Christianity has done with Crucifixion Friday, or as bad. Implying a dualistic notion that experiencing the death of God must be one or the other is ultimately unhelpful. Such a transformation cannot neatly fit into a expectation that we are better after it and were worse than before it. We will try to convince ourselves that this is true, as I have, but I can’t honestly say whether I was happier, better, more whole before or after experiencing God’s death.

All I can say is that I am different. That is what transformation means, only that things will be different, forever.

Certainly Mother Teresa’s private journals bear out this tension, revealing her internal misery in spite of how she made the world a more holy place. It was a transformative experience for her, and a profoundly mystically one, too.

But was it good? Bad? Who can say? In mystical experiences such as this, however, I am convinced there is no such delineation.

What I have learned to say, though, is simply this.

God has died.

It is the mystery of faith.

Thanks be to God.