This has to be one of the more surprising life journeys — and surely an example of God’s unfailingly creative penmanship at work:

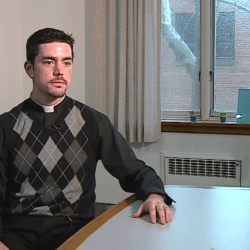

In the morning cold of a farmhouse in the foothills of the Cascades, his hand is stiff as he grasps the broad-edged pen. His eyes have aged. But the 78-year-old priest and calligraphy master plans to write until he dies.

Father Robert Palladino, a priest of the Archdiocese of Portland, is as much evangelist as artist.

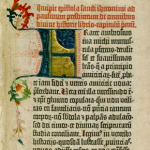

He melds Latin, English and Hebrew letters in ways that show the vitality and universality of Scriptures. He also writes the words of theologians and spiritual masters, usually short, memorable quotes people can live by. He has engraved the texts and notes of ancient chant, which he admires greatly.

“I do things that inspire me in the hope that they may inspire someone else,” said the priest, a former Trappist monk and a widower who was ordained a Portland parish priest in 1995.

Father Palladino is the grandson of an Italian stone mason who came to the U.S. and was recruited to work on St. Francis of Assisi Cathedral in Santa Fe, N.M., a building finished in 1886.

Young Robert, the last of eight children, grew up in Albuquerque, N.M., a half block from the Jesuit-run parish where his grandfather had built the school.

As a boy approaching adolescence, he would walk home from serving at Mass and pray. One day a thought hit him.

“There I was concerned about so many things and there is the Lord in his house,” he recalled. “I decided I wanted to spend my life being closer to the Lord.”

After graduating from high school in 1950, he entered the Trappists, who had a monastery north of Santa Fe on an old dude ranch. His hair was shaven and he wore a scratchy woolen hood. He and the other monks pulled rocks out of arid fields in an attempt to farm. One priest who came to join the monastery left after just half a day.

In his second year as a monk, he continued developing a long interest in handwriting. One Trappist, a former professor who knew calligraphy, began giving him lessons. The young monk soon had the task of writing certificates to thank donors and crafting nameplates and directive signs.

“In a silent monastery, signs do come in handy,” Father Palladino told the Catholic Sentinel, newspaper of the Portland Archdiocese.

In 1955, the Trappists decided that their New Mexico land lacked what was needed for farming and headed to Oregon.

He was ordained in 1958. His superiors, noting his love of music, asked him to take over the choir, which sang Gregorian chant in Latin. Liturgical prayer, the main work of the monks, took place eight times a day.

By the mid-1960s, the Second Vatican Council brought changes to monastic life, including the replacement of Gregorian chant. Father Robert was devastated. Chant, for him, made the word of God memorable and alive.

“For me the important thing is always the text,” he says. “Chant brings out the words better than any other music. It was the ideal liturgical music for me.”

Other parts of Trappist life were changing and he felt he no longer fit.

Read on to find out what happened next.