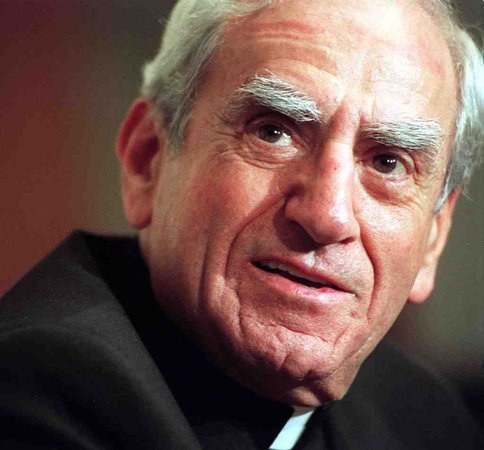

He was a rarity: a Brooklyn priest (who grew up down the road from me in Queens) who became a cardinal. The definitive obit, from Rocco:

He was the ultimate man of the law. How bitter the irony, then, that his days would end under a cloud of court scrutiny.

At 9.15 tonight, Anthony Cardinal Bevilacqua — Seventh Archbishop of Philadelphia, founder of the Catholic world’s first diocesan ministry dedicated to the pastoral care of migrants, arguably the father of modern canon law in the United States — died in his sleep at his apartment at the city’s St Charles Borromeo Seminary. He was 88, and had been suffering from cancer and dementia over recent years.

Born in Brooklyn to Italian immigrants who would raise ten children, the future cardinal’s grit, smarts and relentless work-ethic singled him out from an early age. Known as “Tough Tony” to his seminary students and “Bevy” among friends, his sense of discipline and prominent hatred of cheese often concealed a softer side, one that led him to night school in his 50s to study for a civil law degree in order to serve the needs of a new generation of migrants.

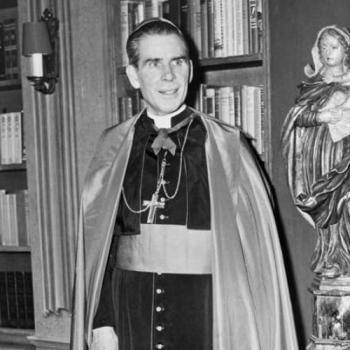

Ordained in 1949 and named chancellor of Brooklyn in 1976, Bevilacqua became an auxiliary to Bishop Francis Mugavero in 1980, was tapped to lead the diocese of Pittsburgh three years later, and in late 1987, was introduced as the successor to John Cardinal Krol as head of the 1.5 million-member Philadelphia church.

Blessed John Paul II elevated Bevilacqua to the College of Cardinals at the consistory of 28 June 1991, conferring on him the title of St Alphonsus on Via Merulana, the mother-church of the Redemptorists. Eight years earlier, his star had been set on its trajectory after the then-auxiliary spearheaded the American implementation of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, followed quickly by his successful mediation in the case of Mary Agnes Mansour, a Michigan nun who stoked the local hierarchy’s protest by taking an appointment as head of a state agency. (Under the agreement, Mansour was released from her community and remained at the department’s helm.)

For all the light of his seemingly omnipresent, fiercely energetic prime, significant shadows would come to envelop Bevilacqua’s tenure over the decade following his 2003 retirement. Over a five-year span, two Philadelphia grand juries would excoriate his administration’s handling of allegations of clergy sex-abuse, the second of them indicting his longtime head of clergy personnel, Msgr William Lynn, whose trial on charges of conspiracy and child endangerment is scheduled to begin in March.

While neither panel would ultimately indict the cardinal, the 2011 grand jury indicated that it “reluctantly decided not to recommend charges” against him.

There’s more. And the hometown paper adds:

Cardinal Bevilacqua was emblematic of the church to which he had devoted himself since age 14: progressive on some social-justice issues, staunchly orthodox on matters of doctrine and sexuality, and unfailingly deferential to the will of Rome.

He was a private man, given to dining alone at the mansion. Yet he delighted in public appearances and was known for his personal touch with the faithful.

He paid official daylong visits to all 302 parishes in the five-county archdiocese, typically saying Mass, touring schools, visiting nursing homes, and posing for photos. He sometimes flung his zucchetto, or skullcap, Frisbee-style into a crowd, and planted his bishop’s hat on youngsters’ heads.

Perhaps the most joyous moment of his prelature here came Oct. 1, 2000, when Pope John Paul II canonized Mother Katharine Drexel, the Philadelphia banking heiress who in 1891 founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

Cardinal Bevilacqua had vigorously championed her cause. He was among the hundreds of Philadelphians clutching umbrellas in Rome that rainy day as John Paul named Mother Katharine to the canon of saints and, at that moment, St. Peter’s Square filled with sunlight.

There’s much more at both links. And more details on his life can be found at his Wikipedia bio.