At the beginning of Advent, I quoted the first line of that timeless chant in my homily, and after Mass a parishioner took me to task. “Deacon Greg,” she said, “you know you said something anti-Semitic in your homily?” I was taken aback. She explained, “That first line in ‘O Come, O Come, Emmanuel’? Where it says ‘And ransom captive Israel’? That’s calling for the conversion of the Jews. We don’t believe that anymore. And there are a lot of us who don’t sing that. You shouldn’t have quoted it.” I told her that was the first time I’d heard such a thing, and that I disagreed. I made clear in my homily, I said, that we are all “captive Israel,” that the world is awaiting redemption. She sighed and walked away.

I did a little Googling afterward. Turns out, there are a lot of other people out there who agree with her:

Such lyrics go beyond the celebration of Christ’s birth found in most classic carols and into Christian supersessionism–the belief that Christianity replaces and improves upon Judaism, and that Jews who fail to accept that “are still wandering and wondering,” as a 1999 dailycatholic.org commentary on “Emmanuel” put it.

“In this 21st Century context, one could reasonably hear those lyrics as hostile toward Jewish people,” said Richard Hirschhaut, director of the Chicago office of the Anti-Defamation League, seconding an opinion offered by Rabbi Joseph Ozarowski, executive director of the Chicago Rabbinical Council.

Meantime, I found this excellent dissection of the hymn at Word on Fire, by Fr. Steve Grunow:

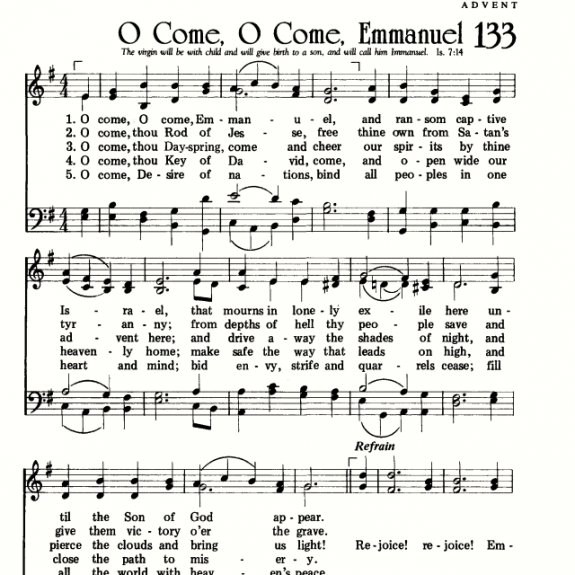

“O Come, O Come Emmanuel” seems to be a stringing together of liturgical antiphons, derived from scriptural texts, which originates in the 12th century. This 12th century rendition appears to be a precursor of a 15th century processional hymn composed by or for a community of Franciscan nuns in France. The version that is used today was arranged in the 19th century. The eloquent words of the hymn are simultaneously lamentation and consolation, recognizing the plight of Israel while at the same time encouraging God’s chosen people to envision the day when the God of Israel will act in an extraordinary way to liberate them from the oppression of their current circumstances.

These are all biblical allusions derived for the most part from the prophet Isaiah, all of which evoke the return of a king to Israel- and not just any claimant to the throne, but someone who would arise from the house of David himself. This imagery and the ethos of the hymn deeply immerse us in the strange world of biblical prophecy, particularly in the Messianic expectations that are redolent of the aftermath of the terrifying events of the year 587 BC.

He goes on, explaining in detail how the haunting hymn to which we are so accustomed is, in fact, far more historically and theologically complex than many of us realize.

Like so many things in Advent, it is about more than just the anticipation of Christmas and the birth of the baby Jesus:

A hymn like “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” is at its best when we accept its purpose: to illuminate the mysterious truth that Christ is God the Messiah, and even while we rejoice at his coming, we wait in hope that the fullness of the restored Kingdom that he bears into the world will one day be revealed.

Meantime, for those who take offense, one blogger has posted this:

Once upon a time, a colleague pointed out an implicit anti-semitism in our traditional carol, “O come, O come, Emmanuel”. She suggested that singing about Israel needing to be ransomed with Christ as the atoning sacrifice was disrespectful of our Jewish sisters and brothers. Over the years I have remembered her challenge. I have sung the traditional words and refused to sing them, I have printed them for the congregation and printed alternatives. My sense is that the theology underneath the traditional words is about the human struggle with attachment and that though the offensive words are not helpful, this theological expression is worthy. Here is one attempt to reframe the familiar opening verse.

O Come, O Come, Emmanuel

And move us from this worldly spell

Our spirits cry in exile here

Until the song of love appears.

Rejoice, rejoice, Emmanuel

For love is coming now to dwell.

UPDATE: A friend who is a convert from Judaism left this comment on my Facebook feed:

IMHO, the meaning behind this, O Antiphon aside, praying for our Jewish bretheran to join us in experiencing Christ’s redeeming love, is the most philosemitic thing we Catholic Christians can do!