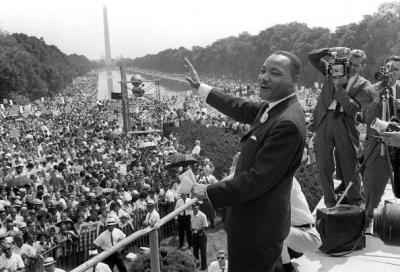

As America marks the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, many people may not know that the words “I have a dream” do not appear in the prepared text for the landmark speech—long considered one of the masterpieces of modern rhetoric.

One of the men who helped craft that speech 50 years ago, Clarence B. Jones, recalled how it came together for the Washington Post a couple years ago:

As we ate sandwiches, our suggestions tumbled out. Everyone, it seemed, had a different take. Cleve, Lawrence and I saw the speech as an opportunity to stake an ideological and political marker in the debate over civil rights and segregation. Others were more inclined for Martin to deliver a sort of church sermon, steeped in parables and Bible quotes. Some, however, worried that biblical language would obfuscate the real message – reform of the legal system. And still others wanted Martin to direct his remarks to the students, black and white, who would be marching that day.

Martin got frustrated trying to keep everything straight, so he asked me to take notes. I quickly realized that putting together these various concepts into a single address would be difficult. Martin would have to take one approach – his own – with the other ideas somehow supporting his larger vision. I kept on taking notes, wondering how someone would turn all this into a cohesive speech. As it turned out, that would be my task.

Eventually, Martin looked to me and said, “Clarence, why don’t you excuse yourself and go upstairs. You can summarize the points made here and return with an outline.”

I sat in my room, flipping through the scrawled pages of the yellow legal pad, struggling to boil down everyone’s perspectives. The idea of urging the crowd to take specific actions, as opposed to a general kind of complaining, seemed one area of agreement. (The march’s organizing manual even had a headline that spelled it out: “What We Demand.”)

A conversation that I’d had during the Birmingham campaign with then-New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller inspired an opening analogy: African Americans marching to Washington to redeem a promissory note or a check for justice. From there, a proposed draft took shape…

He went on to recall the iconic moment that made history:

Martin was essentially reciting the opening suggestions I’d handed in the night before. This was strange, given the way he usually worked over the material Stanley and I provided. When he finished the promissory note analogy, he paused. And in that breach, something unexpected, historic and largely unheralded happened. Martin’s favorite gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, who had performed earlier in the day, called to him from nearby: “Tell ’em about the dream, Martin, tell ’em about the dream!”

Martin clutched the speaker’s lectern and seemed to reset. I watched him push the text of his prepared remarks to one side. I knew this performance had just been given over to the spirit of the moment. I leaned over and said to the person next to me, “These people out there today don’t know it yet, but they’re about ready to go to church.”

What could possibly motivate a man standing before a crowd of hundreds of thousands, with television cameras beaming his every move and a cluster of microphones tracing his every word, to abandon the prepared text of his speech and begin riffing on a theme that he had used previously without generating much enthusiasm from listeners?

Before our eyes, he transformed himself into the superb, third-generation Baptist preacher that he was, and he spoke those words that in retrospect feel destined to ring out that day:

I have a dream . . .

In front of all those people, cameras, and microphones, Martin winged it. But then, no one I’ve ever met could improvise better.

The speech went on to depart drastically from the draft I’d delivered, and I’ll be the first to tell you that America is the better for it. As I look back on my version, I realize that nearly any confident public speaker could have held the crowd’s attention with it. But a different man could not have delivered “I Have a Dream.”

Some believe, though the facts are otherwise, that Martin was such a superlative writer that he never needed others to draft material for him. I understand that belief; fate made Martin a martyr and a unique American myth – and myths stand alone. But admitting that even this unequaled writer had people helping him hardly takes anything away. People like Stanley, Mahalia and I helped him maximize his brilliance. If not, why would Mahalia interrupt a planned address? She wasn’t unhappy with the material he was reading – she just wanted him to preach.