Bob Sonneman—a dear friend, longtime parishioner, retired sacristan and a former Trappist brother—died on December 7 after a brief illness. My pastor asked me to preach the homily at his funeral. The text is below.

+

Over the last few days, here in the parish we’ve all been sharing our Bob Sonneman stories.

We haven’t been talking about his debonair good looks or elegant fashion sense or his sparkling wit. Again and again, the word people use to describe him is “kind.” Or as the reading from Wisdom put it, “a just man…pleasing to God.”

This was a good man.

And, of course, he was a teller of the worst jokes in the world. I was going to begin my remarks this morning with some of his greatest jokes.

Truth be told: there aren’t any. They were all terrible.

But we all have our Bob Sonneman stories.

There was the time he spent part of the morning diligently watering the plants in the sacristy—but no one had the heart to tell him they were plastic.

Or the time Father Passenant was preaching during daily Mass and the lights over the pulpit kept flickering on and off. Father thought he was having a stroke. It turned out, Bob was polishing the light switches in the sacristy.

That was Bob. He gave us a lot of memories and a lot to talk about.

But this Gospel we just heard reminds us: he also offered us something more.

Jesus tells his followers, “Where I am going, you know the way.”

Across 80 years, Bob Sonneman knew the way.

He knew the True North, his guiding star, was Jesus Christ. And he followed that star to the very end.

He showed us the way.

The way of compassion.

The way of kindness.

The way of generosity and joy.

Bob’s journey began in an unexpected place: an orphanage. Bob never said much about the circumstances that put him there. All he ever told me was, “My mother couldn’t afford to raise me, so she gave me up.”

He was raised by religious sisters, and they led him down the right path, as sisters so often do—with tenderness and patience and just enough tough love.

The orphanage was where he learned to love those who were also abandoned, or cast aside or poor.

It was where he learned to appreciate everything and everyone, no matter how humble.

It was where he learned how to see every day as a gift.

It certainly gave him direction—and he discovered that direction early in his life, when he was a teenager, and someone gave him a copy of “The Seven Storey Mountain” by Thomas Merton.

That changed everything. “The Seven Storey Mountain” is the story of Merton’s conversion to Catholicism and how he decided to become a Trappist monk. Bob was inspired by Merton’s love of the Lord, and his description of religious life. He wanted to be like him, to live like him. So after high school, he went to Kentucky and the Abbey of Gethsemani, Merton’s monastery.

He did something radical: he became a Trappist monk.

Being a Trappist in the 1950s meant a life that was strict, even severe. A life of prayer and hard work. It was physically demanding. In the winter, you’d wake up at 2 in the morning to get up for prayers, and you’d dip your finger into the holy water font in your cell and find the water frozen. It was that kind of life.

Being a Trappist also meant taking a vow of silence.

Knowing Bob’s sense of humor, I think we can all agree: a vow of silence was a good thing.

At Gethsemani, Bob was given a new name, Brother Daniel. He was put to work baking the monastery’s famous fruitcake. Sadly, his career as a baker ended rather abruptly when he accidentally blew up the bakery.

When that happened, the monk in charge broke his vow of silence—using words that mentioned God in ways you usually don’t hear in a monastery.

Despite periodic explosions and setbacks, Brother Daniel loved the life of the monastery—the prayer, the silence, the simplicity. He cherished it the rest of his life.

Shortly before my ordination, Bob gave me a full four-volume set of the Liturgy of the Hours, with all the prayers, all the offices.

It was a generous gesture. But I realize now, he wasn’t just giving me books.

He was giving me…what had shaped him.

He was sharing what had moved him, and grounded him in the monastery. He was giving me something that, for so many years, defined his days.

He was giving me prayer.

He was helping to show me the way.

I will always treasure that.

He stayed at Gethsemani for 16 years. I once asked him why he left the Trappists. He said simply, “I thought I could live the Gospel better out in the world.” Just before he left, he passed Thomas Merton in a hallway. Merton had heard Bob was leaving. Using the sign language of the Trappists, he asked Bob if it was true. Bob said it was. Merton smiled and signed back in reply, “Good for you.”

Bob, of course, eventually found his way back to New York. He worked for a time on Wall Street and finally ended up here in Forest Hills, where he volunteered at the parish, served as a lector and eucharistic minister, and ran the small gift shop we used to have near the entrance to the church. Eventually he became the sacristan. That was when I first got to know him.

He was unfailingly generous with his time and his money—sometimes, too generous. Homeless men and beggars found their way to the sacristy door and Bob never turned them away—he always gave them a few dollars, which I know infuriated Msgr. Funaro.

Bob didn’t care. When he saw people who were outcast, or struggling, or down on their luck, or homeless, he didn’t see problems to be dealt with or strangers to avoid.

He looked at them and saw Jesus.

“Where I am going, you know the way.”

Bob really did know the way.

Early in December, my wife and I went with Father Antonin to see Bob in the hospital. He had lost a lot of weight, but he was the same Bob, ready to share a bad joke and offer that big smile. Fr. Antonin anointed him. I remember Bob closing his eyes and extending his open palms to be anointed and I thought to myself, “He’s ready to go.”

He was ready to follow the way, all the way, to the dwelling place prepared for him.

Whatever loss we feel this morning, the Gospel tells us, “Do not let your hearts be troubled.” Our hearts can only be filled with gratitude and prayer. Gratitude, that Bob was a part of our lives. Prayer, as we pray that God’s mercy will lead Bob to a place of perfect peace.

During Advent, we spend our days waiting. We wait to see Christ. My prayer for Bob is that his wait is over, that he is gazing at last upon the Lord, surrounded by so many others who accompanied him on his way and who were a part of his story…

…His mother who loved him but had to let him go…the sisters who raised him…the Trappists who prayed with him…the hungry and the helpless and the lonely who turned to him again and again for a kind word or a spare dollar or maybe just a bad joke.

I have to believe this is true: In Bob Sonneman’s heaven, people actually laugh at his jokes. They always ask to hear one more.

I like to imagine that Thomas Merton may have been there to welcome him, with the same words he left him with all those years ago.

“Good for you.”

Good for you, Brother Daniel.

Good for you, Bob, my friend.

Thank you for showing us the way.

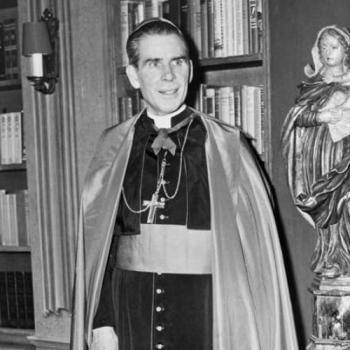

[img attachment=”130107″ align=”aligncenter” size=”full” alt=”sonneman3971478101_1331893168186500737_n” /]

Photos: by Deacon Greg Kandra