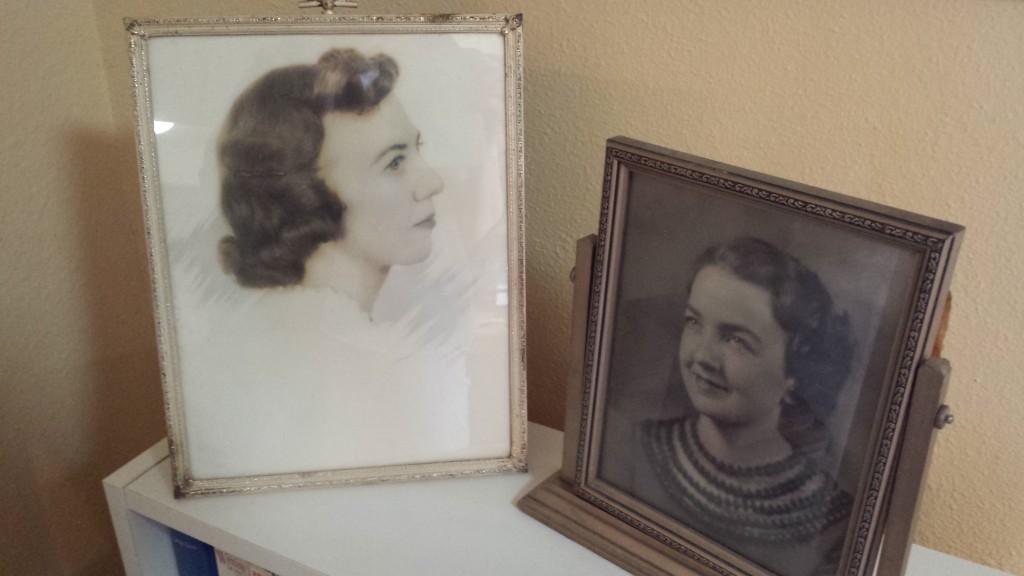

Yesterday would have been my mom’s 101st birthday. She died at the age of 90—at home, of congestive heart failure, with all her affairs and family in order, in the home she and my dad bought in the mid 1950s.

This weekend, we’re hosting a birthday party for my mother-in-law, who turns 90 today. About 35 people, almost all family and some from halfway across the country, will converge at our house to eat cake and celebrate her life—and she’ll probably laugh more than anyone at the party.

This morning I received an email from a friend who recently traveled home to the Midwest after wintering down South. On the drive, as her mind wandered, she was surprised to hear the voice of her mom, who passed away years ago. They had an excellent chat, she says. Her mom was encouraging and had a lot to say.

My friend Kathy’s mother is 96 years old and has pancreatic cancer. Yet when Kathy and her family visited her over the weekend, she was as upbeat as ever, and they made paper snowflakes into the evening.

Life is filled with memories, stories and celebrations of older women right now. On International Women’s Day, it seems an appropriate time to thank them.

These are women who were born, came of age and raised their families before women’s lib, before parity, before birth control.

Their lives have spanned sea changes in social and cultural mores, and they’ve adapted. Sometimes unwillingly, of course. They may still gripe about today’s lenient parents and the benefits of one-room schoolhouses, but they adapted nonetheless.

Today, when we’re focused on how we can move forward as women, it’s important to remember those connections to the past.

So I want to reprint an excerpt of an essay I wrote that appeared in a book called My Mother’s Garden. It’s based on a conversation I had with my mom a few months before she died….about gardening, one of her favorite pastimes.

“People didn’t have nurseries back then,” my mom says of her grandmother’s era, “and they were better gardeners.” In the early 1900s, her grandparents lived near Myrtle, Missouri, just above the Arkansas line. Their house sat on Doniphan Road.

With her fingers, my mom draws the layout of her grandparents’ property on the coffee table. “The house was here, and the apple orchard was back here,” she says. “Granddad planted every kind of apple there was. And the barn was back here. The garden was large, between the orchard and the barn.”

She remembers it well because she and her older sister Grada spent many days there. The girls’ own home was separated from the Fairview schoolhouse by a creek. When the water rose in the spring and became impassable, my mom and Grada lived at their grandparents’ house, which was on the same side of the creek as the school. Despite the felled three that served as a bridge, my mom fell in the creek once. “They had to wrap me up and put me in front of the fire,” she says.

A lilac bush hid one corner of my great-grandmother’s porch; a prolific vine climbed a trellis at the other end. “She had beautiful roses,” my mom says. But most striking of all were the plants beyond my great-grandmother’s garden: the wild roses growing along the fence across the road, right in front of an entire field of wild daisies.

“Grandpa wasn’t fond of those daisies,” my mom says. After all, they usurped perfectly good pasture ground. For my mom, that field of daisies taught an early and simple lesson: In a world of constant work, sometimes wonder trumped utility.

In her childhood, the lines between work and play blurred as she gathered gooseberries for pie or ate black haws from wild bushes on the way to school, or climbed down into the cellar, using the trapdoor in her grandparents’ living room floor, to gather apples and sweet potatoes.

She and Grada sat on the front porch for hours at a time, peeling apples and peaches from the orchard. Their grandmother then spread out the slices on a bedsheet and left them to dry on the roof before she and her daughter turned them into a twelve-layer cake. “Sumptuous,” my mom says. It is one of many things that she declares as “The best thing I ever ate.”

So there it is. A picture. A verbal photograph. My great-grandmother was a lilac bush, a peach tree, a safe harbor from a swollen creek, a view of daisies dancing in the sun.

I am thinking about the ways we come to know one another. I will never hear the exact words of my great-grandmother or grandmother, although they speak through the generations in the language of flowers. But I can get a glimpse of them, and the glimpse becomes a picture, just as every river or apple tree or gooseberry bush is part of the earth and is the earth, all at the same time.

Debra Engle is the author of The Only Little Prayer You Need. You can find her on Facebook and at debraengle.com.