In the last few posts, we have been noting that any attempt to apply the biblical call to justice by directly translating what the Scriptures say into our present context may be problematic for two reasons.

First, which we addressed in the post, “Doing Justice Today: what does it look like? Understanding Empire,” we noted that we often have a poor, or at least a very limited, understanding of the empires that resided behind the biblical world.

In addition, which we addressed in the posts, “Understanding Empire” and “What does the Bible say about empire?” we noted that we often have little to no understanding of the biblical view of empire.

Secondly, which we will begin to address in this post, is the fact the applying the biblical conception of justice to our present context is problematic because we often have a skewed conception of our own contexts.

This raises the questions: What do we mean by a skewed conception of our own context? And how does this happen?

By a skewed conception of our own contexts, we mean that we all perceive reality through our own set of lenses and oftentimes those lenses are the ones that make us the most comfortable.

How does this happen?

To ask: “how could we begin to adopt a narrative that has a skewed conception of our own context?” it might be best to begin by asking how such disdain for human life in an empire like Rome could have been tolerated? How could some live such lavish lives when surrounded by oppression and abject poverty?[1] And how could those who suffered such oppression (the 90%) have allowed it?

(Mind you that we should be reminded that we have hardly scratched the surface in detailing Rome’s gross inequities and its’ blatant disregard for human life.)[2]

There are, of course, a multiplicity of answers to such questions. Let’s note two of them.

First, most often those with power, which is usually those who are the primary beneficiaries of the system, wield the power of the sword. Consequently, the oppressed typically have no practical recourse to bring about change.

In Rome, for example, when uprisings did occur, they were met with the utmost severity.[3] (look at what is happening in Myanmar or Hong Kong today).

Secondly, all societies and the individuals within that society weave narratives in order to account for the present circumstances.

These two factors in part explain why so many people in Germany could allow Hitler to exterminate 6 million Jews and millions of others who were deemed not worthy of life. They had come to accept one of the many narratives: e.g., it is for the good of the nation, or the stories of death camps are not true, or, they are greatly exaggerated, or there is no use in speaking up because we will just suffer the same fate.[4]

Of course, the narratives are often controlled by those in power. If others attempt to write alternative narratives, especially narratives that counter the status quo and upset the balance of power, those in power are quick to deal with them.

NB: This is one reason why Jesus told parables: i.e., in order to veil the true, revolutionary nature of His kingdom: “To you has been given the mystery of the kingdom of God, but those who are outside get everything in parables” (Mark 4:11).

This is also why many others resorted to the use of apocalyptic imagery. Such imagery shrouded the empire from understanding the revolutionary nature of the community’s narratives.

Now, it is still hard to believe that those in the Roman empire who suffered from Rome’s oppressive system (the 90%) would believe that the gods had established those in power to rule the empire and serve the people as the savior of the world.

But we must be reminded that nearly every aspect of Roman life served to reinforce this narrative. Civic life was marked by consistent feasts and festivals that affirmed the divine nature of the ruler and his role in the empire.

Much more can be said, but let us turn to the question: what does all this have to do with the issue of justice in the world today?

I’m glad you asked. Everything!

Doing justice today

First, we must recognize that we also weave narratives to explain our present world and our place in it. This is part of being human.

The problem is that overturning these narratives is often met with great resistance. And for good reason. The narratives we weave typically result in our comfort and acceptance of the status quo. Especially when we are the beneficiaries.

This is why I have taken so much time to get to this point in the discussion.

Simply mentioning “justice,” as if everyone agrees with what justice means and what justice looks like in a given cultural context, is not possible. We do not all agree. And we have narratives that stand in our way.

Until we (and by “we” I mean everyone, including myself, and in particular the Christian community to whom I am writing) are prepared to honestly evaluate the narratives that we embrace, which often serve to justify our beliefs about the world and our place in it, “doing justice” will remain nothing more than a faddish expression, dismissed by some and embraced by others, but one that does little to actually affect any substantive change.

The reason why the first post in this series was titled, “Injustice, maybe I’m the problem” is because I have come to learn not only about injustice but about how, in many cases, I was the source of it.

Unless we are willing to reassess our own narratives, there is no value in pressing forward.

I believe that this is why Jesus spoke in parables. His parables were veiled efforts (available to those who have eyes to see and hears to hear) to disguise the revolutionary nature of His kingdom from those in power.

Now you must be aware that if you begin to place your narratives at the feet of Jesus, your whole world will change. This change may be liberating and exhilarating, but it may also be filled with grief, shame, and regret.

“the one who has ears to hear, let that person hear” (Mark 4:9).[5]

Maybe this is why the Gospel begins with, “the kingdom of God is at hand, repent . . .” (Mark 1:15).

to be continued . . .

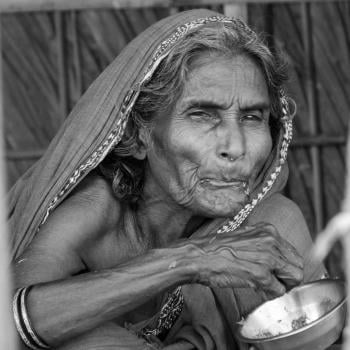

[1] Of course, many do this very thing in various parts of the world today. In India, the wealthy are know to build tall dwellings only to have a view that overlooks a slum.

[2] And this does not even bring into the conversation the ancient Assyrian and Egyptian empires.

[3] After the death of Herod in 4 BC, outbreaks of revolt rose up around Judea. Josephus, a Jewish historian of the late first century, notes that 2,000 were crucified as a result of the upheaval. Josephus, Antiquities.

[4] I personally have a copy of a Nazi propaganda film made c 1941 titled, Dasein Ohne Leben (Existence without Life). The film was shown on National television throughout Germany and depicts severely handicapped persons as being “not worthy of life.” The film suggested that government resources used to keep these people alive would be better served to help the nation build new homes and new cities so that Germany may flourish. Ina Friedman writes, “Fifty years after the end of World War II, few people are aware that Jews were not the only victims of the Nazis. In addition to six million Jews, more than five million non-Jews were murdered under the Nazi regime. Among them were Gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, blacks, the physically and mentally disabled, political opponents of the Nazis, including Communists and Social Democrats, dissenting clergy, resistance fighters, prisoners of war, Slavic peoples, and many individuals from the artistic communities whose opinions and works Hitler condemned. The Nazis’ justification for genocide was the ancient claim, passed down through Nordic legends, that Germans were superior to all other groups and constituted a ‘master race’” (See: https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/publications/se/5906/590606.html). The people, many of them, bought a narrative that justified the killing of millions.

[5] Author’s translation.