Luciano Floridi, who has been developing the philosophy of information as a new area of inquiry since the late 1990s, argues we are living through a scientific revolution that is changing how we understand our nature and our role in the universe.

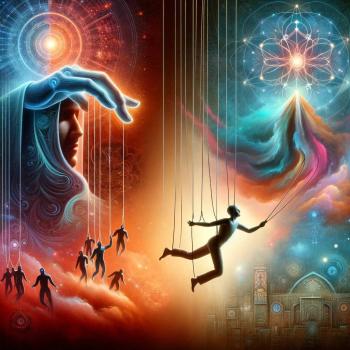

Floridi identifies this as the fourth major revolution of the modern era to transform how we see ourselves and the world. The first of these revolutions, following Copernicus, established a heliocentric cosmology that displaced the Earth and humanity from the center of the universe. The second revolution came with Darwin’s explanation of natural selection, which changed understandings of human origins and biological adaptation. Following Freud, a third revolution in psychology complicated a view of the mind as something simply rational. Now, when we perceive that the creation and proliferation of intelligent machines is having a significant impact on us and our reality, it is because we are experiencing an information revolution that casts “new light on who we are and how we are related to the world.”

The information society we inhabit today has its roots in the earliest information and communication technologies of clay and stone, but digital and networked technologies have profoundly altered our lives and the world during the last half century. Our information society, Floridi observes, has become “like a tree that has been growing its far-reaching branches much more widely, hastily, and chaotically than its conceptual, ethical, and cultural roots. The lack of balance is obvious and a matter of daily experience.” It is “high-time,” he continues, to expand our understanding of the nature and impacts of our information age “and thus give ourselves a chance to anticipate difficulties, identify opportunities, and resolve problems.”

The implications of Floridi’s observations go far beyond confronting questions about managing information overload and being distracted by new media. We have faced these challenges before. (See, for example, Chad Wellmon’s Organizing Enlightenment: Information Overload and the Invention of the Modern Research University.) More significant is what the information revolution reveals: “the intrinsically informational nature” of human agency and our environments. We are becoming more aware of how fundamental information and its technologies are to our understanding of who we are and what constitutes our reality.

This means that the concept of information and our information technologies are much more interesting than we may have yet realized.

From Basil of Caesarea through Francis Bacon, for some time science and technology have been considered as sources of revelation. Both contemplative reflection on as well as active engagement with nature are part of the human quest for knowledge. Over a millennium ago, Hugh of St. Victor identified three types of knowledge: theoretical (such as physics and theology), practical (such as politics and economics), and technological (such as agriculture and medicine). All knowledge, he believed, leads to God: “theoretical knowledge as a remedy for ignorance, practical knowledge for vice, technological knowledge for physical weakness” (see Diogenes Allen’s chapter on the “Book of Nature” in his Spiritual Theology).

We should expect, therefore, for information science and technology to be important sources of revelation for all domains of knowledge, including theology. A few theologians, such as Arthur Peacocke and John Polkinghorne, have explored implications associated with the information revolution. Peacocke described God’s interactions with the world as a “holistic, top-down continuing process of input of ‘information’” that intentionally shapes people and events. Polkinghorne suggests the human soul is an “information-bearing pattern” that is carried by one’s material body. Beyond these more contemplative integrations of information and theology, there is much more to be considered about the active integration of information technologies and theology: What do these reveal to us about our roles as creators, cultivators, and curators in creation—and even in new creation?

To help us think about the needs of our information society, Floridi gives us an image of a tree—a helpful and ancient figure. One of the earliest representations of this figure is associated with knowing too much and not accepting limits. Another representation, also ancient but apocalyptic, is associated with knowing a new life. Both figures, and the theological narrative that connects them, can inform how we attend to the wild tree of the information revolution.