This dog has something to teach us about being human. He appears in Blade Runner 2049, a great movie, IMHO.

One of my favorite scenes is the climactic moment when the two protagonists finally meet. The next-gen “replicant” LAPD officer “K” (Ryan Gosling) has been searching for his mysterious predecessor, “Deckard”, the original Blade Runner (Harrison Ford). It’s a classic setup for a high-anxiety contest to discern whether they will be friends or foe. Fear ignites the tensions of fight or flight—the primal instincts that lurk in the heart of every man and beast. Our pulse rises in sympathetic response as we watch.

The actors are bona fide movie stars, but the one who steals the scene is a scruffy old dog of indiscernible heritage. No, not Harrison Ford. I’m talking about the dog, Deckard’s dog, the real dog. Or is it? In 2049, we are not so sure anymore what’s real and what’s not. This is the first thing Officer K wants to know—he nods at dog and asks, “Is it real?” Deckard doesn’t answer. He and his dog just look at K in silence, and we are left to wonder.

This simple question, “Is it real?”, sums up the moral angst that runs through the entire movie. Why does K care if the dog is real? What difference does it make? It makes all the difference in the world. This is the existential question of identity that K cannot avoid: “Am I real?”

You see, Officer K is a “replicant”, a state-of-the-art bioengineered android nearly indistinguishable from a human being. In a sense, he is a weaponized humanoid. To make him even more lifelike, memories and emotions have been programmed into him. He has flashbacks to childhood experiences which evoke behaviors characteristic of real human emotion. Officer K’s identity crisis leads him to question the authenticity and moral integrity of his own programming. This is but one example of the dystopian future depicted in the film. Like so many other good sci-fi books and movies, Blade Runner uses apocalyptic imagination to explore the existential questions posed by our race to unleash new technologies.

The big question for Officer K is whether he is a real person. The story invites us to imagine what it would be like to be inside his skin. If his memories are not real, then how can he be a real person? If his emotions and will are controlled by his programming, then how can he be (or have) a soul? We can imagine these questions are on his mind when he asks if the dog is real. The obvious alternative is that the dog is a replicant, a bioengineered quadruped, just as K is a bioengineered android.

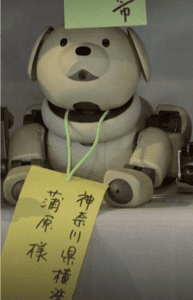

For the same reason that a dog was first sent into space, dogs will likely face these trials before humans. After all, the LAPD has not yet deployed replicants, but robot dogs have been available for years.

Sony was the first to commercialize the robot dog AIBO in 1999. AIBO stands for Artificial Intelligence Bot, and also sounds like the Japanese word aibō, meaning “pal” or “friend”. Sony released a new and improved “litter” of the robot dogs annually, and sold 150,000 over seven years. Then in 2006, Sony killed the breed and shut down robot dog operations. (Earlier this year, Sony resumed production of AIBO dogs with a vastly improved generation.)

The demise of AIBO robo-pets left many customers heart-broken. They had come to love their robo-pets. Some even participated in religious services to honor the spirit that had animated their dead robot. This religious sentiment is based in the belief that natural objects and even inanimate objects possess spirit(s) (kami, 神 in Japanese). Religions devoted to this belief are called animism (from the Latin anima, meaning breath and spirit of life). Animistic beliefs can thus be seen to sustain the possibility that robot dogs might have spirits.

The boundary line between human and cyborg is fuzzy and will become fuzzier in the future. Perhaps animism offers an easy way out of the dilemmas of apocalyptic imagination. I wonder how Officer K would feel about it. I wonder if it would answer his question about what it means to be real?

In the Bible, all animals, including dogs and humans, are called “living souls” (nephesh-ĥaya) [Genesis 1:30, 2:7]. This definition of soul gives a different answer to Officer K’s question. The soul is neither a possession of an object, nor a “feature” programmed into a creature. Soul is not an attribute. It is rather the ontological reality of becoming a creature formed by God and into whom God has breathed life [Genesis 2:7].

There is a stark difference between animistic and biblical understandings of soul, but this does not dismiss the pain of loss felt by the owners of “dead” robot dogs. Even a robot dog can be a companion. The feelings of loss are real. But perhaps the deepest blessing of a relationship with a pet is how they make humans more human. I shall have more to say about that, and the difference between robot dogs and real dogs, in a future post.