I am among the many who thoroughly enjoyed TheGood Place. In addition to generating popular interest in moral philosophy, providing humorous clips for introducing the trolley problem and ethical theories (with Peeps Chili!), the show also points to a fundamental challenge we face living in an advanced technological society.

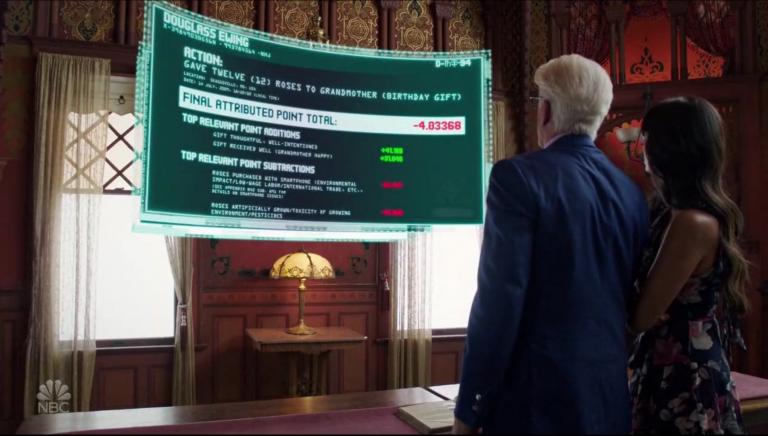

The philosophical climax of the show occurs in the episode “The Book of Dougs,” when a simple, ostensibly good act is shown to be entangled with a range of ethical issues. Doug gives a dozen roses to his grandmother and earns points for thoughtfulness and making Grandmother happy. But these points are wiped out because the roses were purchased with a smartphone (raising ethical issues about environmental impact, low-age labor, international trade, “etc., …”) and the roses were artificially grown (raising ethical issues about the toxicity of the growing environment and pesticides). Doug’s tainted act reveals that the complex condition of the modern world has broken the point system that determins who is worthy of entering the Good Place, and everyone in this world is on the road to hell.

Albert Borgmann calls this technological condition the devise paradigm: invisible systems operate beneath the visible surface of what we perceive and experience, alienating us from more substantial things and practices. With digital technologies, we can speak of an even more complex digital device paradigm, which introduces a layer of surveillance that can further alienate us from ourselves and the world.

The Good Place’s ultimate reimagination of the afterlife as a place that provides opportunities for living a good life is a mostly satisfying solution for the show’s characters, leaving viewers with a sense of hope in the face of mortality (which—spoiler alert—has a place in the afterlife). As one reviewer notes, the show is “so full of hope and joy (even in the midst of hell itself) that [it] invites us to practice hope and joy in our present-day hells.”

Although viewers may be encouraged to live better lives and make the world of the living a better place, the show’s eschatology is mostly individualistic—the ultimate end is individual annihilation. Individual identities and relationships are important, but after all aspirations and reconciliations are realized these are left behind for a presumed merging with the universe. Chidi, who says “for spiritual stuff you’ve got to turn to the east,” describes the end of life as a wave returning to the ocean.

The end of The Good Place, however, leaves unresolved the central issue it raises so well: How do we live ethical lives within the reality of our digital devise paradigm? Better lives realized in the perfected Good Place seem to have little influence on the world of the living. Posthumous ethical improvements do not provide the living with a vision of a better world, and without new information any reformation of the digital device paradigm is unlikely. The afterlife is mostly a clean-up operation.

There are, of course, alternative eschatologies. Many emphasize enduring identities and relationships, and some even address our technological condition. One, shaped by the apocalyptic imagination, emphasizes the image of the city—an image that signifies hope for human relationships in a new community, and hope for human agency, which includes our technological glories.