The recent New York Times article, “Facebook’s Next Target: The Religious Experience,” raises a number of technological and theological questions. The technological questions cannot be answered, since Facebook requires its collaborators to sign nondisclosure agreements and very little is revealed in the article about “how churches can ‘go further farther on Facebook.’” But there should be much more discussion and disclosure about the theological implications of these partnerships.

This much is disclosed:

A Facebook spokeswoman said the data it collected from religious communities would be handled the same way as that of other users, and that nondisclosure agreements were standard process for all partners involved in product development.

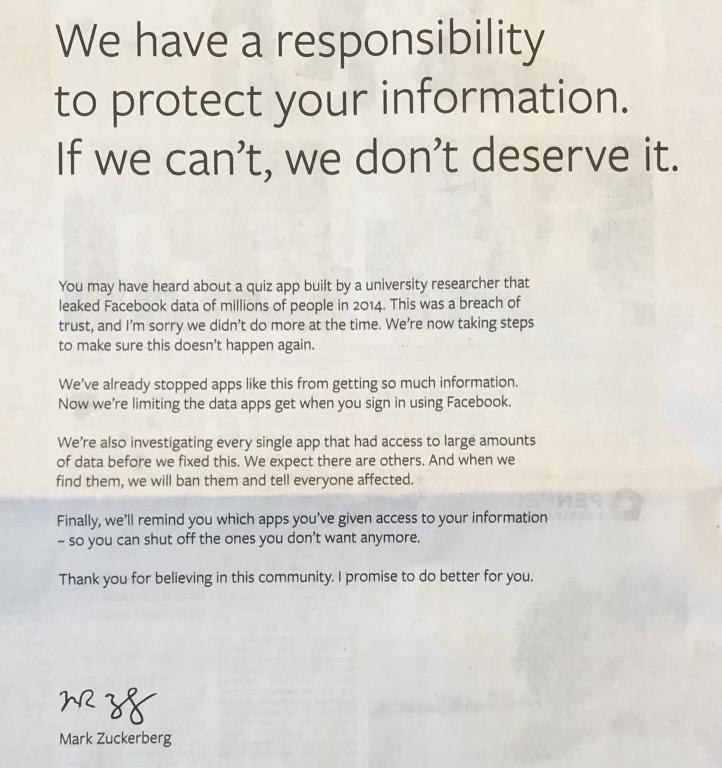

This disclosure, by an unnamed spokesperson (Mephistopheles?), should raise a number of concerns among religious leaders and members of religious communities. Facebook has a long history of mishandling data (see the extensive Wikipedia article on “Privacy concerns with Facebook” and, as an e.g., recall the “Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal”).

In addition to Facebook’s data collection and use practices, Facebook can be critiqued for the ways it manipulates attention for advertising revenue, facilitates the spread of misinformation and disinformation, and fragments society through algorithmically intensified divisions. Do we want Facebook “shaping the future of religious experience itself, as it has done for political and social life”? If my pastor or denomination were to sign an NDA with them, that would cause me to reconsider the extent to which I trust my church or denomination.

(I followed up with my denomination, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), which was mentioned in this article and became a “Facebook faith partner” last December. This partnership involves a discussion group—a group in which I cannot participate, since I do not have an active Facebook account. A denominational spokesperson told me to follow up with Facebook with my concerns about privacy.)

I understand that religious communities need help exploring and implementing new strategies for digital engagement. I obtained funding for and led a project about church digital transformation during the pandemic, and I contributed to a recent ebook on the topic edited by Heidi Campbell. After reading this Times article, and learning that religious organizations “seem undeterred by Facebook’s larger controversies,” I wish I had thought of educating church leaders about companies such as Facebook who would see a “strategic opportunity to draw highly engaged users onto its platform … [and] embed their religious life into its platform, from hosting worship services and socializing more casually to soliciting money.”

All of this, however, is technological prolegomena to the theological questions we should be asking.

At a virtual faith summit last month, Sheryl Sandberg said, “Faith organizations and social media are a natural fit because fundamentally both are about connection.” That equivocation obscures what connection—or, better, relationships, are ultimately for in communities of faith: realizing a greater purpose and world. Facebook has not succeeded, as either a corporation or as a platform, to earn trust related to matters of truth and justice (see “Criticism of Facebook”). And its goals, as Sarah Lane Ritchie points out in the Times article, are not aligned with the values or goals of most faith traditions.

People of faith could critique Facebook for its misalignment with a variety of theological or religious doctrines—the purpose of creation, hope for the future, ways we create a better world, and how humans thrive in the present. Facebook as a corporation views users as commodities, seems determined to create a word that is dependent on Facebook, and exists to maximize profits. Facebook does not simply exist to connect the world—it seeks to envelope the world with its technology and profit considerably from this dominance. The company’s leaders appear to believe these ends will make the world a better place.

A few years ago, when critics of Facebook and other tech companies started to promote the idea of time well spent free of manipulative platforms, Mark Zuckerberg began speaking of time well spent on Facebook. In a more ambitious arrogation, Zuckerberg recently announced his multi-billion-dollar desire for Facebook to become a “metaverse company.”

The idea of the metaverse is drawn from Neal Stephenson’s dystopian novel Snow Crash (1992). And it was a dystopian idea:

in the book from which the current metaverse craze originates, not only is our world in ruins and most people are eking out precarious lives in dire poverty, but the metaverse itself is a place that is addictive, violent, and an enabler of our worst impulses. It’s an exceedingly dark vision.

As contemporary commercial hype, the metaverse now has something to do with better interfaces for integrating online and offline experiences. In Zuckerberg’s words:

you can think about the metaverse as an embodied internet, where instead of just viewing content—you are in it. … the metaverse isn’t just virtual reality. It’s going to be accessible across all of our different computing platforms; VR and AR, but also PC, and also mobile devices and game consoles. …

I don’t know about you, but a lot of mornings, I reach for my phone by my bedside before I even put on my glasses, just to make sure, get whatever text messages I got during the middle of the night and make sure that nothing has gone wrong that I need to jump into immediately upon waking up. So I don’t think that this is primarily about being engaged with the internet more. I think it’s about being engaged more naturally.

When Stephenson was asked a few years ago what he thought of “the prospect of a Zuckerberg-controlled Metaverse,” he said (after “low laughter and a very, very, very long pause”):

I would say that anything that gets invented has got results, and some of those are predicted and some are not. There’s no fixed process for predicting the results and controlling what happens. At some level, it boils down to people’s capacity to act as socially responsible, ethical individuals.

If the idea of the metaverse can be responsibility reconceptualized as less of an escapist online reality, and enable a better blending or integration of online and offline experiences, then it could be a constructive element of our postdigital future—i.e., that time when the digital is a regular part of our lives. But an important and more hopeful aspect of becoming postdigital is having critical perspectives on digital technologies, technology companies, our technological society, and the different beliefs that are shaping our future.

For example, Zuckerberg believes we are headed in the direction of more experiences that “are less anchored physically.” The digital is always physically situated, whether one is staring at a computer screen, wearing a virtual reality headset, or seeing the world through augmented reality glasses. All are physically anchored, and living well across these various forms of engagement—as well as with non-digital forms of engagement—will require wisdom as well as imagination from diverse sources.

(For a sense of some of the limitations of a strictly technological imagination, consider how this discussion about governance of the metaverse—“the holy grail of social interactions”—in the end devolves into technical concerns about interoperability.)

People of faith can bring their ancient wisdom into these critical discussions proactively—perhaps even with Facebook (but without the NDAs). Simply rejecting digital engagement and enhancement is not the correct response; faith perspectives can help us create and realize a better technological society.