“The Social Dilemma” opens with powerful quotes from powerful people.

They laud the technology as a “force for good.” A visionary tech entrepreneur sums up excitement and idealism that inspired so many like him in the tech industry:

“These tools have created wonderful things. They’ve reunited lost family members. They’ve found organ donors. I mean they were meaningful, systemic changes happening around the world because of these platforms that were positive!”

After extolling the boon to humanity that social media technology brings, they confess and grieve over the damage done:

“Yeah, these things, you release them and they take on a life of their own. And how they’re used is pretty different than how you expected.”

One after another, these leaders express serious concern if not outright fear over the platforms they have invented, built, marketed and empowered.

The interviewer asks the obvious question, “So, what is the problem?”

This question stops each of them in their tracks. They are dumbstruck. Gobsmacked. Stunned, and speechless. No one has an answer. They stare blankly into the camera. They drop their heads in despair. They laugh nervously. Not one of them can answer. The next hour and a half of this documentary tries to answer that question.

And make no mistake, there is a problem, and these people have helped create it. They have been leaders, entrepreneurs, CEO’s, chief engineers, and key designers of the software and computational engines that make money by shrewd manipulation of massive amounts of personal data. They all know there is a problem, and yet they cannot name it.

The theological answer is obvious—sin.

Why are these leaders dumbstruck by the question? Perhaps they are reluctant to bring faith into the discussion, because they don’t want to sound “religious”. Or perhaps they lack a faith perspective that understands the reality of sin.

It turns out that a practical, down-to-earth, perspective on the reality of sin is necessary to name the problem, and to navigate our way forward with wisdom in harnessing new economic and technological forces.

So it has always been, in one sense. “There’s nothing new under the sun” [Ecclesiastes 1:9]. Technology has always been a part of human culture, and it has always been subject to misuse. Some would argue that technology is not the problem, but misuse of technology is the problem. Does that mean we just need to be “nice” on social media? No, that’s a superficial response and misses the deeper issues.

While it’s true that technology per se is not a new problem, this particular technology does indeed create new problems which society has not seen before. The experts interviewed in the documentary point this out as well—the scale, speed, ubiquity and massive coverage of huge swaths of communications on every level, from intimate personal connections, to micro-targeting, to mass-media are unprecedented. This is not merely a matter of degree. It is a qualitative change. The massive reach of manipulative techniques, governed by no authority other than the economic self-interest of the platform providers is already having a pronounced effect on culture, as seen in the divisiveness, “fake news”, and political discord.

Idealism and the Tragedy of Institutional Sin

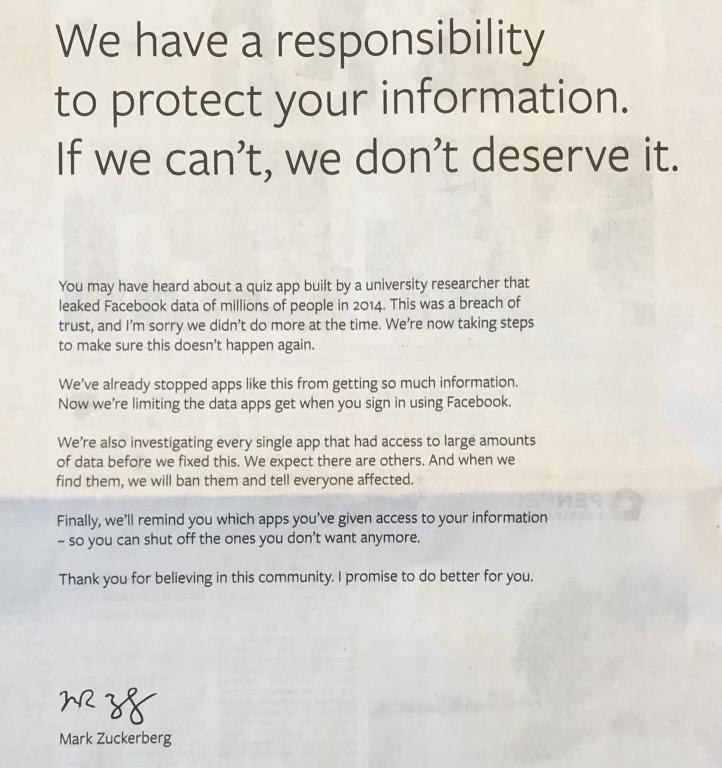

How did something aimed at being so good and idealistic, and developed by such well-intentioned people with good motives and good values, go so wrong? The answer is that this idealistic vision—of social media as a platform for good—lacks a realistic appraisal of the way sin creeps in and corrupts institutions. Idealism quickly succumbs to hubris in the form of self-serving ideologies. This is the tragedy that befalls techno-utopian visions.[1]

Sin seeps in like water through cracks in the foundation of a house. “Sin burrows into the bowels of institutions and traditions, making a home there and taking them over.”[2] Ashforth and Anand describe this type of sin as on ongoing process of corruption in which “idiosyncratic social constructions tend to become woven into a self-sealing belief system that routinely neutralizes the potential stigma of corruption.”[3]

This is exactly what happens when a social media tech company is driven by a blind faith in itself, its founder, and/or its technology as an unblemished good. The organization defines itself in terms of “a self-sealing system of beliefs.”[4] Charles Taylor refers to this mindset as a “Closed World Structure.”[5]

To enable human relationships is indeed a gift that social media enables. Nonetheless, the sinister, corrupting force of sin is continually crouching at the door of every opportunity the social media company sees to monetize the personal lives of its users.

The good news is that attention to the reality of sin exposes the corruption in self-serving ideologies, and ethical leaders will recognize the dangers of corrupting forces, confess the limitations of their technical solutions, and repent from manipulative practices that do not have the better interests of users and society in mind.

The good news is that a realistic vision of the brokenness of the world system sees the light shine in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it [John 1:5].

[1] Baker, Bruce D. (2020) “Sin and the Hacker Ethic: The Tragedy of Techno-Utopian Ideology in Cyberspace Business Cultures,” Journal of Religion and Business Ethics: Vol. 4 , Article 1.

Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe/vol4/iss2/1

[2] Plantinga, Not the Way, 75.

[3] Blake Ashforth, and Vikas Anand, “The Normalization of Corruption in Organizations,” Research in Organizational Behavior, 25 (2003): 1-52, 16.

[4] Ashforth and Anand, “Normalization of Corruption,” 17 [italics in original].

[5] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,2007), 551f.