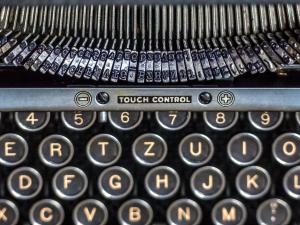

I have just finished the Netflix anime series Violet Evergarden, which looks at the life of a brutally efficient and seemingly emotionless former solder with a fierce dedication to her former major, who was her mentor and only friend. Following the war, Violet tries to settle back into civilian life as a ghost writer for hire – an “auto memory doll” – travelling through the land with her typewriter and writing letters and plays for royalty and commoner alike. The driving source of irony here is that Violet, so capable to expressing the inner life of others, is also at the same time so unaware of any emotional life of her own. There is a visual cue for this motif, given that Violet the scribe lost both her hands during the war, and must rely on mechanical prosthetics.

However, in the course of writing the letters for her clients, she slowly becomes aware of her own interior life. Her emotions, hopes and identity slowly start to emerge before the viewer as she those of her clients become committed to paper. The theme of love, so obvious to the viewer but veiled to Violet, and yet so crucial to her identity, slowly becomes internalised as she writes the various nuances of the love of her clients to others. Eventually, Violet the traumatised, emotionless “auto memory doll” gives way to Violet the restored human person, thanks to the task of writing.

This series underscores the crucial importance of writing for the formation of human persons, even as Plato’s Phaedrus also warned of this technology’s role in the abstraction of human community. We more often present ourselves to others through writing than through aural or personal contact, and identities are formed in this process of written expression, both in reality and in the minds of others. Increasingly, these scribed identities are formed independently of the identities we express with our mouths and bodies. This remove between our person and our writing is more acute in an age where smart devices are now the prosthetics we carry, and typing becomes the increasingly normalised mode of writing rather than by hand. We see the fruits of this remove in the anonymous and increasingly aggressive combox wars. Given this, there may be more Violets in the world than we are willing to admit.

Nevertheless, the relationship between the written and the personal reminded me of the Millis Institute’s Benjamin Myer’s important essay on blogging as a theological discourse. There he cites the communications theorist Walter Ong, who stated that “more than any other single invention…writing has transformed the human self”.

Drawing upon Foucault’s concept of the “technologies of the self”, Myers explored the idea of writing as a form of askesis or self-care. He then turned to the examples of ancient writers from Marcus Aurelius to the Church Father Athanasius and their admonition to their disciples to “write themselves” as a means to purify their identity, both to themselves and before God. For then as now (even in its more abstracted form), the sinews of the human person (and here we must also think the new creation in Christ) are being woven with every pen and keystroke.

I can think of no better way to end this post than with Athanasius’ instructions from his Life of Antony, which Myers cites:

Let us each one note and write down our actions and the impulses of our soul as though we were going to report them to each other… Molding ourselves in this way, we shall be able to bring our body into subjection, to please the Lord, and to trample on the devices of the enemy.