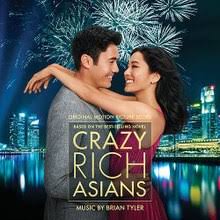

I had the chance to see Crazy Rich Asians in the movies. It features a set of mainly Singaporean-born American Chinese millenials attending a wedding in Singapore (there is more than this, of course). As a migrant from Singapore, I could not resist. For a summary of my reactions, please see fellow Asian Catholic blogger Justin Tse’s post on the movie here.

To elaborate, the most interesting thing about the movie was that it avoided the most typical asian stereotypes, and the flick featured an array of colourfully wacky characters. However, the very point that endeared me to the movie was also the very thing that disturbed me. It was not that the Asians depicted in the movie were free from stereotypes, but there did not seem to be a normal Asian in the house. To live up to the “crazy” in the title, the movie seemed to slap every imaginable quirk on the characters. The casting of Ken Jeong – famous for his depiction of the highly unpredictable Chang in Community – emphasised this point.

What it did mean was that the Asian viewers of the movie did not know what to expect from these characters and so were equally entertained by the movie. Yet, you might forgive those same Asian viewers for leaving the movie feeling slightly obligated (and not in a good way) to become blank slates on which fifty shades of cray could be slapped.

The impression of the Asian as blank slate reminded me of the depiction of Judge Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridien, which is picked up by the philosopher RJ Snell in his Acedia and Its Discontents (I have written more on that book here). Amidst a landscape where almost everyone had a tattoo signifying a belonging or a past (albeit a brutal one), the Judge had no such markings. The Judge belonged to no one, to no tradition, to no community. Like the Asians in the movie, the Judge was a blank slate.

This constant drive to be autonomous – free from connection – Snell argued was the foundation for the vice of acedia or sloth. More than laziness, sloth was the desire to be free from any kind of order that was not imposed by one’s own will, to live in no world other than one that he or she has made.

I raise sloth here because the characters in Crazy Rich Asians paid little homage to the traditions in which they were raised. Sure, a lot of Singaporean food was seen to be consumed, but whether it was in the hawker centres or in the kitchen of the Young family home, the dense particularity that comes with the food’s preparation did not feature greatly, only the instance of its consumption. The millenials in the show, covered as they are in layer upon layer of slick, expensive, and ephemeral fashions, show little sign of connection to the lands of their birth. Indeed, an underlying theme of the movie is the whether showing affinity to tradition is a good thing for an Asian millenial. Being an American produced movie, one might argue that the characters were simply being “American”, but even America has traditions that the characters show next to no affinity to.

Some might argue that if the resistance to tradition and communal connection was what underpinned acedia, then Eleanor Young (played by Michelle Yeoh), the devout Christian with her fierce insistence on the old Hokkien principle of “Our Own People”, would be the epitome of virtue. Yet, even she manifests the vice of sloth, though not through a show of individualism, but in a show of an emaciated form of community.

In Acedia and Its Discontents, Snell argued that part of living the life of virtue, a life of real communal connection, is recognising life as a gift from another, which then gives a heft of meaning to the world. We accept the gift of life from God, and do not set the terms by which the gift is received. We live a life of virtue in a life of active acceptance of a gift from another as other, and all the meanings that come attached to that gift. By contrast, the vice of sloth bleaches meaning from the world, as the only meaning that one accepts for the world is the meaning imposed on it by the self. This kind of imposed meaning distorts the inherent significance of the thing, but also thins things out.

For all of Eleanor Young’s initial displays of Christian piety at the beginning of the movie, her living out of that life as one of receptivity to another is cut short by her insistence that the Hokkien principle of “Our Own People” override the biblical imperative to care for the stranger, “since you were once strangers” (Ex 22:21). Moreover, “Our Own People” goes into hyperdrive, for the problem lies not in the fact that Rachel (played by Constance Wu) is not Chinese, but that she is the wrong type of Chinese. Her otherness was not a thing to be welcomed, but a virus to be resisted through the insistence of a form of tradition bleached of its original meaning. The tradition that Elanor upholds is one she decides what is or is not traditional, which is a form of autonomy hiding under a thin communal disguise, and thus another form of the vice of sloth.

If there were characters that showed a way of resistance to this manifestation of the vice of sloth, they were the very ones that were the characters that barely rated a mention. These were the singlet and hijab wearing uncles and aunties who worked in the hawker stalls to support their families. Relying on the traditions embodied in recipes that they grew up with, they must to prepare food sold in the stalls and kitchens- a painstaking process of maintaining tradition and community we barely see – to be consumed by crazy rich asians – an instance on glaring display over and over again.