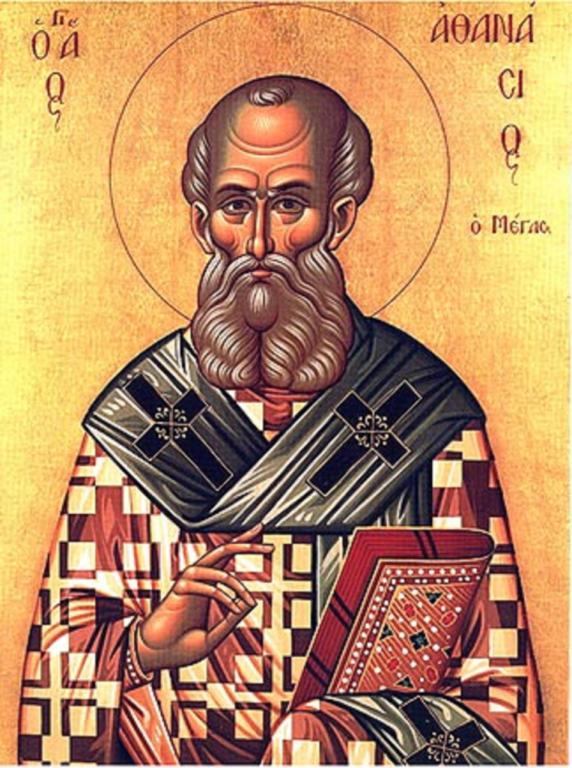

You know, Athanasius was probably, as we might say, a piece of work. I don’t see him as the wise and wonderful guru sort, all gentle and calm like the Dalai Lama. He was probably pretty fiery and insufferable, just the sort we like to tune out. We don’t mind our political commentators like that (especially if they’re demonizing our opponents), but God forbid our spiritual leaders display any challenging, prayerfully considered, theologically wise, but ultimately alienating convictions about faith. But Athanasius falls in a long line of anointed, godly leaders who just plain weren’t cuddly: Moses, Elijah, Jeremiah, Paul… What we believe really matters because it changes how we live.

I wonder what Athanasius would say about the Church today. Would he see a thriving, faithful community of those who live and move in the life of the Trinity, made visible in the words and deeds of Christians?

Oh bother (as Pooh would say). Let’s not get all Eeyorish.

One of Athanasius’ key works is called On the Incarnation, a deeply influential essay about the meaning of the incarnation. And yet, this is no Christmas sermon. Unfortunately, the Church today largely gets sermons and teachings about the incarnation in December, when the overall glitter of mangers and angels and stars and little children dressed up like sheep largely distorts the profound theology that should be shaping our lives. We bring a live camel down the aisle of our churches in order to “liven up” the powerful story, and then all we see is the camel (especially if it sits on you).

Where Arius saw in Jesus’ birth a lesser status of the Son, Athanasius saw the divine glory of the Son. Arius argued the Son’s sub-divine nature from the fact that he accepts a weakened, emptied position as a human in order to fulfill the will of God. Athanasius argued the Son’s fully divine nature from the fact that he accepts a weakened, emptied position as a human in order to fulfill the will of God.

How can this be?

Athanasius begins by examining what indeed salvation means, and understands from the outset that salvation is the ultimate purpose of our existence. God intends—and has always intended—that we “be conformed to the likeness of his Son” (Rom. 8.29). “He chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight … adopted as his sons through Jesus Christ…” (Eph. 1.4-5). Salvation in the confess-your-sins-and-accept-Jesus-into-your-heart sense is only the first step in the great transformation that God intends: “to bring all things in heaven and on earth together under one head, even Christ.”

In that light, we must, as did Athanasius, define salvation as the true knowledge of God. Salvation means knowing God in that personal, trusting, completely abandoned way. And John would agree: “Now this is eternal life: that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (Jn. 17.3). And Paul would agree: “I consider everything a loss compared to the surpassing greatness of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord…” (Phil. 3.8).

Whatever other biblical/theological labels we want to use to describe this experience—election, justification, sanctification—the goal remains: to know God.

“But,” Athanasius reminds us via Anatolios, “through the misuse of free will, humanity has lost access to the knowledge of God and descended into a downward spiral of ignorance and moral depravity.” I like the way Anatolios describes this: “a fixed trajectory of reversion toward nothingness.” Without the knowledge of God, we are like space walkers whose lifelines to the ship have been severed. We slowly drift away into empty, dark, lifeless cold. “Sin is the willful disorientation that makes nothingness the end of human being rather than the departure point of human participation in the divine.”

God in his justice could let us drift away from himself, but because his purposes in creation were self-giving love, he refuses to let us go. He regenerates the knowledge of God through the incarnation, and all of Jesus—words, actions, death, resurrection—both reveals the heart of God and opens the door to that heart.

Now, whereas Arius could twist that whole scenario in such a way that divine transcendence was preserved in the Unbegotten One, and divine immanence was achieved in the Christ, Athanasius gives us a wildly different picture. Instead of two opposing poles—transcendence (divine) and immanence (created)—Athanasius tells us that both these two are actually attributes of the divine being, and they find their expression in God’s self-giving love for us.

Let’s stop here for a minute to really focus on Athanasius’ great claim. This is how Anatolios describes it:

The mercy of creation consisted in God’s bestowing upon humans a participation in the Word through which they could attain knowledge of the Father. Characterizing God primarily in terms of philanthropia [love for humanity] and mercy—attributes whereby God can transcend his own transcendence—explains both why no mediating being is needed and how the incarnation accords with the character of God’s being and the divine deportment in the act of creation.

This is how Mulhern understands it:

God’s number one purpose in creation is love and mercy. We see this when he himself stoops down—transcending his own transcendence—to give us real understanding of the Fatherhood of God. He does this by inviting us into the Word of God’s love, that is Jesus Christ. God’s great holiness, sovereign glory, incomprehensible power, and perfect wisdom are not set aside in Christ, but “translated” into gentle touch, authoritative teaching, healing kindnesses, sacrificial love, and mighty renewal. Jesus gives us true knowledge of God (salvation) because he reveals the nature of God: self-giving.

Now look at this God. Instead of Arius’ isolated, distant God who sends an inferior emissary, we have a God whose very essence “has to be conceived as a dynamic outgoing movement.” The essential movement is within the heart of God; “divine self-abasement is integral to the biblical character of God.” The emptying and abasement of Christ, the kenosis, actually indicates his divinity because it reveals “the general character of God’s self-humbling love for humanity.” We can say, as Anatolios does, that God’s very character is Christological, by which we mean that the movement of God in Christ—self-emptying, serving, loving, sacrificing—reveals the center of divine being.

Anatolios points out that, for Athanasius, Paul’s Christological hymn in Philippians 2 sings of both the humanity and the divinity of Christ—the former acknowledging his humiliation and suffering, and the latter acknowledging his divine heart of love.

This is all a great deal deeper, wider, and more glorious than most nativity reenactments can give. The humility, compassion, and gentleness of the Baby in the manger indicate not just the will of God, but the very essence of God. The inner life of the Trinity—“the intra-divine delight of the relation of Father and Son”—is replicated on a human scale in the Infant invitation.

The invitation? Ah, that is where Athanasius brings in a discussion of the Spirit.

Note to Reader: This series on Trinitarian Spirituality explores the history and spirituality behind the shaping of the Nicene Creed using Khaled Anatolios’ Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011) as guide and inspiration. It’s best to begin at the beginning: An Introduction.