I’ve been pondering a troublesome passage—James’ harangue about works (James 2.18-26). It’s not a passage I particularly like. It’s prickly. You can tell he has someone in mind, some shocking example of an argument when someone shirked a work of kindness or generosity and begged off with, “Well, I have faith. And that’s all that counts.”

I’ve been pondering a troublesome passage—James’ harangue about works (James 2.18-26). It’s not a passage I particularly like. It’s prickly. You can tell he has someone in mind, some shocking example of an argument when someone shirked a work of kindness or generosity and begged off with, “Well, I have faith. And that’s all that counts.”

The Marthas among us, perhaps, read it with their hands on their hips and say, “Uh-huh. What did I tell you? Hellooo? Get your rear into gear and do something.” The Marys, so quietly pondering the teachings of our Lord, look around in a surprised annoyance as someone taps us on the shoulder and tells us that if we’re not involved in good works, we’re not really Christians at all. “Um, but all we want to do is sit at the Lord’s feet and ponder. And maybe write blogs. Or read a book. Aren’t these enough?”

It’s no wonder that Martin Luther suggested we gently demote this book—like downgrading Pluto from the canon of planets.

As I wrestled with this passage, however, I am struck by James’ use of the story of Abraham, the Model Extraordinaire of being justified by faith, not by works. James knows exactly where to poke, almost as though he’d read Paul’s argument about Abraham in Romans. Here’s how Paul argues it:

For if Abraham was justified by works, he has something to boast about, but not before God. For what does the scripture say? “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.” Now to one who works, wages are not reckoned as a gift but as something due. But to one who without works trust him who justifies the godly, such faith is recognized as righteousness (Romans 4.2-5).

Paul so carefully outlines the ways that Abraham, believing God, was justified by that belief before he did anything to merit justification. The work of believing itself was justifying.

This is echoed in Jesus’ response to the lunch crowd in John 6: “’What must we do to perform the works of God?’ Jesus answered them, ‘This is the work of God, that you believed in him whom he has sent.’”

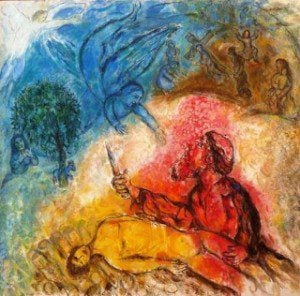

Yet here, in James, Abraham is justified not when he believes, but when he offers his son Isaac on the altar, that dreadful moment of absolute relinquishment and the decision to let go of the son he loved and, so it seemed, to lose the promises of God.

Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was brought to completion by the works.

So what, then, is the work that saves? What is the work that justifies? It can’t really be the attempted sacrifice. If it were, then the Genesis claim (Gen. 15.6), which Paul builds his theology around, would be false. Abraham was justified long before Isaac came along, so the moment of Mount Moriah, the moment when Abraham was prepared to rip his own heart out, was circumstantial—anecdotal even—not substantial.

What then? What is the work that justifies?

And here we might find some common ground between the mystic Paul and the pragmatist James: In Galatians 5, when Paul is again talking about this earnest desire for justification before God, he tells us that “the only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love.”

And who was Abraham loving on Mount Moriah?

Here we have the synthesis between the gospels, the Pauline arguments, and James. Abraham was indeed justified by a work—believing in God, trusting God—and we see that belief and trust in the ultimate act of love: that moment when Abraham weighed his love for his son (and we know the crazy depths and heights and widths of a love like that) against his love for God; and his love for God—a love without full understanding—won.

Abraham was justified by his love for God. Back before children, in that dark moment of aging despair, Abraham groped for God and believed in the word placed in his hand. He clung to that word, for years, holding it close: an heir…God said…I believe. And that belief was incarnated in Isaac, and Abraham loved Isaac. But a justifying love grew in a different place, a place that was even deeper than the desire for an heir and the love for a boy. In the depths of his heart, that confidence in God’s trustworthiness turned into a passion for God, a love for God that transcended even the word to which he clung.

To believe in God is to love him—as he is, not as we imagine him to be. This is what was tested on Mount Moriah. When God reveals himself in suffering, in violence, in incomprehensible pain—are we still loving him? Or do we only love him as we wish him to be—gentle, generous, and open-handed? On the mountain of sacrifice, Abraham was confronted with his love and he found that he actually loved God even more than his son. His faith was expressed, then, in love. And so he was saved.

Here, a favorite verse, and an unlikely one for someone like me—from the Apocryphal books, and a footnote at that! But still, exquisite and, at this wee resting place, surely inspired:

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of love for him, and faith is the beginning of clinging to him (Sirach 25.12).

Photo Marc Chagall