“Everything depends upon God, all Christian life begins with grace, all prayer is inspired by the Holy Spirit, but we can learn to respond to, or cooperate with, this divine action upon us.”

So wrote Martin Thornton, an Anglican priest and author, writing on what he dubs the English school of spirituality. He shows his chutzpah by actually using the word “ascetical” in the title of his book: English Spirituality: An Outline of Ascetical Theology according to the English Pastoral Tradition. Trust me, “asceticism” is not the kind of word publishers want to put on snazzy book covers these days.

Asceticism conjures images in our heads: of scrawny saints moping around in their dank cells and nibbling on a crust of bread … every other day; of religious fanatics flogging themselves with nasty leather whips; of solitaries living on top of poles for decades. And yet, of course, it is asceticism that we see in the Olympic athletes—discipline, training, formation, all for the goal of victory. And despite the sacrifices those athletes have made, despite the injuries and obstacles, we see them filled with joy, elated by their experiences, celebrating their abilities to transcend limitations.

“Ascetical theology makes the bold and exciting assumption that every truth flowing from the Incarnation, from the entrance of God into the human world as man, must have its practical lesson. If theology is incarnational, then it must be pastoral.”

Thornton, like many writers of Christian spirituality who also have a deep historical foundation, explores the ways that the Spirit has taught God’s people to cooperate with grace, to make it less of a transaction, and more of a bubbling spring, a well of salvation. He suggests that the English school has a unique and powerful role to play, even now, even here in this torn American context: “sane, wise, ancient, modern, sound, and simple; with roots in the New Testament and the Fathers, and of noble pedigree; with is golden periods and its full quota of saints and doctors; never obtrusive, seldom in serious error, ever holding its essential place with the glorious diversity of Catholic Christendom. Our most pressing task is to rediscover it.”

So, if you’re interested, that’s what we’re going to do. Thornton spends the first part of his book exploring the state of the Church (in the 20th century, when it was written), the real meaning of asceticism for Christians today, and the way English spirituality derives from scripture, particularly the New Testament. Then he traces the influences of Augustine, Benedict, Bernard, St.-Thierry, Victor, the Franciscans, and Aquinas before launching himself into the English iterations of this spirituality: Anselm, Gilbert, Hilton, Julian, Rolle, Kempe, the Caroline divines, and more.

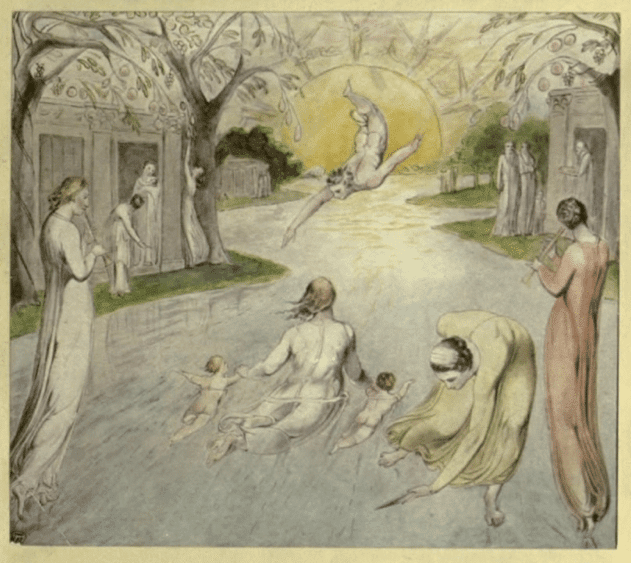

I’m not interested in re-presenting his material, but, as best I can, interpreting it for the lay reader whose heart yearns for a glimpse of a vision that might lead to something more than Bible study, church attendance, and moral rectitude. I’m thinking of Mrs. Turpin’s vision, who saw a “vast swinging bridge extending upward from the earth through a field of living fire,” a “vast horde of souls tumbling toward heaven,” as Flannery O’Connor wrote. I’m thinking of William Blake’s vision of life—harmonic, rich, whole. Can you imagine it?

Images: 1908 Summer Olympics, public domain; The River of Life, William Blake, public domain