This semester I’ve been teaching a class called the Spiritual Journey and Human Development. We examine the life of faith and how it develops, assuming that it does develop over time; we consider how sometimes we seem to make progress, sometimes we regress, and sometimes we just slow down to a near state of immobility. For example, we examine biblical models of the spiritual journey: How did Joseph’s faith develop through the crises of his life? Can we see Elijah’s faith growing? What about Job? How did his faith change? What stages of faith can we see when we look at the life of Paul?

We also consider some historical models: Where was God in all the years of Augustine’s pre-conversion life? What can we learn from Ignatius of Loyola’s encounter with the Lord and subsequent prayer life? How did John Wesley’s faith change over the years? How has Desmond Tutu’s spiritual life developed?

Then there are also models in literature that can serve as models: Pilgrim’s Progress, and Christian’s journey to the Celestial City; Dante and his dark journey through hell up to Paradise; John Ames reflecting on his life in Marilyn Robinson’s Gilead.

One of my favorite journey images from literature is in Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Bilbo and the dwarves are traveling through Mirkwood, the great and ancient northern forest in Middle-Earth. They are instructed repeatedly to stay on the path—it’s the only safe way through; stay on the path, do not wander, you will reach your end. But the journey is so long, so very long; the forest feels so heavy and dense, they’re running out of food and drink, they begin doubting Gandalf…did I say they were to stay on the path? Bilbo climbs a tree to see if he can see the end of the forest, but because he could not see that he was in a bit of a valley, it looked like the trees went on forever…when actually they were near the end of the forest. And they leave the path, wandering into quite dreadful conditions, including spiders. (As good a reason to stay on the path as I’ve ever heard.)

The readings for the Fifth Sunday in Lent are rich in instruction about how to persevere in this journey, how to face the challenges along the road as we move through life in Christ and toward Christ; they speak of the memories of our past, our anticipation of the future, and how to live in the present and not get stuck or wander from the path; they speak of navigating time.

Time is weird, and the weirdness of it pops into our awareness on strange occasions. As we age, we look back on different versions of our selves with all its different relationships and understandings and daily realities:

- There’s the me that lived with my parents

- The me that was a college student

- A young married me

- A mommy me

- A graduate student me

- Where did they go? How are they present? Have I shed those personas?

- How do all these experiences play into my journey? Am I journeying? Or am I stuck?

Some people are stuck in the past—whether good or bad—and replay old wounds, old friendships, old accomplishments like a never-ending loop; others reject the past, and refuse to think about painful times. Some people are so launched into an anticipated future that they aren’t ever really present; others are so fearful of the future they constantly barricade themselves behind emotional and financial security gates.

In reflecting on this mystery, Augustine wrote: “I look forward, not to what lies ahead of me in this life and will surely pass away, but to my eternal goal. … You, my Father, are eternal. But I am divided between time gone by and time to come, and its course is a mystery to me. My thoughts, the intimate life of my soul, are torn this way and that in the havoc of change.”

“Torn this way and that in the havoc of change”—indeed. He said it well. Do we not feel this? This “havoc of change”? Around us, between us, within us? How do we live in this tension between “time gone by” and “time to come”? How do we keep moving?

First we read Isaiah (43.16-21), who gives the people of God a national message about this. He reminds them of the singular key event from their past that had shaped their identity: “This is what the Lord says—he who made a way through the sea, a path through the mighty waters, who drew out the chariots and horses, the army and reinforcements together, and they lay there, never to rise again.”

The Exodus had always been the defining reality of their spiritual journey; they were known as the people whom God rescued from slavery in Egypt and brought into the Promised Land; they were chosen for God’s particular work. But approximately 1000 years later, Israel’s spiritual journey had completely deteriorated, undone from within by worshipping other gods and subverting every form of social justice; their experience had become entangled in exile and despair; they remembered this long-ago miraculous work of God, and felt, quite hopelessly, that the “good times” were gone; the deliverance and chosenness and blessing had slipped away and they were left with the shattered memories of greatness as they languished away in exile in Babylon.

Psalm 137 records the feelings of those times: “By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion. There on the poplars we hung our harps…”; memories of lost glory locked the people into despair, and they had no foreseeable future.

By the rivers of Babylon, Gebhard Fugel, 1920

Consider the way early 20th c. artist Gebhard Fugel captures this scene; note the harps in the background; all of the faces are downcast, some with hands clutching their heads, except the man in the middle, whose face is upturned and the light shining on it. Through Isaiah, God tells his people to let all those lost glories go; forget the former things; stop thinking about them; do not dwell on the past, whether they’re thinking of what they had or thinking of their failures; their spiritual journey now demanded a willingness from them to look for God’s new work, to expect God’s new work. “I am about to do a new thing!” What do you think: is the man in the image looking for the new thing?

Paul gives the Philippians (3.4-14) a similar message, using his present own life and assets. He lists his lifetime achievement awards, his “confidence in the flesh”: “circumcised on the 8th day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for legalistic righteousness, faultless.” Impeccable qualifications—good ancestry, good family of origin, unchallenged devotion to God, meticulous attention to all the laws, a good boy and over-achiever in every sense; he knew the scriptures forward and backward; he was traveled, educated, elite; and yet, with a nearly violent tone in his writing, he verbally shreds his resume.

Not a single piece of his rights and privileges and accomplishments and qualifications mean a thing; in fact, he says, they’re rubbish, worthless, completely forgettable; even worse than worthless, they are weighing him down in his rush toward Christ; they are handicaps. “I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me … forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead.”

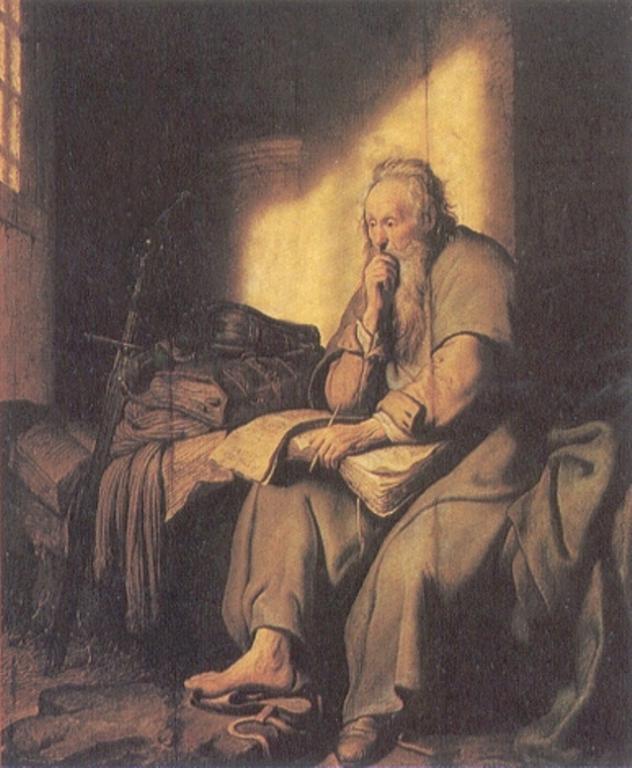

Scholars believe that Paul wrote this letter to the believers in Philippi from prison, so his pressing forward, straining onward is most certainly a spiritual movement, from the heart, yearning for Christ, longing and anticipating the joy of union with God in Jesus Christ.

Saint Paul in prison, Rembrandt, 1627

See the way Rembrandt paints him with few possessions; the sword a symbol of his impending death; he is imprisoned, but you can see his mind and heart are not bound to the cell—they strain forward in thought and prayer; his journey toward Christ rushes on.

In the gospel (Jn 12.1-8), Mary speaks not a word, but her singular, memorable action speaks volumes about what this “pressing forward” actually looks like. Mary has a pint of pure nard, which was very valuable. So let’s speculate. Today Chanel goes for $4200/ounce and there are 16 ounces in a pint. So in this comparison, the perfume might have been worth $67,200. Another way to think of it is to understand that a pint of nard cost an average year’s wages, so you think of your equivalent of that pint of perfume.

Perfumes are meant to be used sparingly, a sprinkle or spritz here or there, making a small vial last for a long time; when they’re that expensive, you clearly operate on a scarcity mentality—you don’t buy a case of the stuff at Costco when you run out. To own something like this was to have a tidy buffer, a savings account, an emergency reserve in time of need. In one grand movement, she takes what is precious and spends it all…on Jesus’ feet.

Mary anointing Christ’s feet, Illuminated manuscript, c. 1500

In this late medieval illustration, note the two with the palms forward on Mary’s side of the table, most likely Martha (nice for once to see her sitting down) and Lazarus, fresh from the grave; now note the disciples arraigned opposite—questioning, judging, murmuring; and Judas, standing in the foreground with his purse; explain yourself, they demand; how do you justify this?

Feel her extravagance; be offended by it, and you’ll understand how incomprehensible it was to others. They were, in Matthew’s version, “indignant,” at the wastefulness of it, at the complete impracticality of it—it had real economic value, and she completely disregarded that; she not only was not thinking of herself and her possible need of it in the future, she was not thinking of anyone else either: not the poor, not her brother or sister. She was thinking only of Jesus.

Nor was it a terribly private act of devotion; the house filled with the fragrance of the perfume. Yet as Jesus said of her in Luke: “there is only one thing necessary, and Mary has chosen it.” You see we hoard our goods, our treasures—whether the accumulation of good memories and the privileges of our past, or the accumulation of our achievements and reputation and rights, or the accumulation of our assets to secure our futures—and our clenched fists keep us from receiving with open hands the new thing God wants to do in our lives.

The Israelites, by clinging to God’s work in their lives in years past and fretting over their present distress, couldn’t see that God was doing something now, something new. Paul realized that the more he embraced his achievements, rights, privileges, accomplishments, fame, honor, and respect, the less he could gain Christ. Mary understood that letting go of the most expensive thing she owned, something that could make her future more secure, was actually no loss at all; rather, it was love poured out, heedless of the reckonings of the world.

But we, here, in this precarious 21st-century world, we calculate our spiritual lives so carefully. Nearing the end of Lent, we are now at the stage of evaluating our success, or perhaps we’ve given up, or we’re gritting our teeth until the end. Lent so often becomes a minutiae of record-keeping: I gave up dessert for Lent … but, is a doughnut dessert? Does drinking cocoa with the kids violate the no-chocolate rule? Since the phone interrupted my ten minutes of prayer, should I make it up later? Do I really have to finish all those verses of scripture? Will it count if I don’t? Will it count? Will those checks we write to the church “count”? will our faithful attendance at church “count”? will our efforts count?

Earthbound, Evelyn de Morgan, 1897

Here we are, hoarding and calculating, “captains of our destinies,” stacking the little piles of our own treasures. We want so badly to score a few points with God and with ourselves. We examine our lives and sift through them for the “good stuff,” weigh it all against the “bad stuff,” and sit by the side of the road in our journeys counting our pennies, trying to secure a reasonably good future. And as we sit there, stacking up our past and plotting for our future, on the road God is present though we do not see.

These scriptures tell us not to put our eyes on our Lenten achievements or our Lenten failures, but forget the past and press forward. Extravagance, the art of not calculating, is the very essence of worship, for it is lavish, unreasonable, seeking no return on investment, seeking no insured future.

Nineteenth-century French priest, Abbe de Tourville, wrote: “Do not keep accounts with Our Lord… Go bankrupt! Let our Lord love you without justice! Say frankly, ‘He loves me because I do not deserve it; that is the wonderful thing about Him; and that is why I, in my turn, love Him as well as I can without worrying…I know of no other way of loving God. Therefore, burn your account books!”

So, here at the winding down of Lent, we are invited to consider carefully what we’re clinging to in the past, how it weighs us down in the present, and what it means to open ourselves up to the new thing God is doing. This is the only way forward on our journeys.

Yet this is not about self-discipline, not an ascetic practice, not a mustering of self-control, not a surge of effort. Rather, the scriptures teach us that this letting go and surging forward is a natural result of two things:

1) We must genuinely believe God is present and active in this world, in our world, no matter how messed up it seems. The prophet addresses the Israelites in a state of collapse; their circumstances are chaotic and disastrous; Jerusalem is in ruins, their spiritual heritage is lost, their future gone dark. Their experience is a desert and wasteland. Yet they’re being called to believe that the God who once did such a great thing in their past is now still involved, and he is bringing new life, new hope, new possibilities. “I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? … You are my chosen people, the people whom I formed for myself so that they might declare my praise.” Your present suffering is not a sign that God has abandoned you; you are chosen; God continues to form you; your destiny is worship.

Paul has put all his trust and all his confidence in the fact that the life he was living—a life of persecution, suffering, homelessness, hostility, and uncertainty—was not in fact a waste of his gifts and assets. He hadn’t forfeited anything of real value, in fact all that was holding him back from the prize—the heavenly call of God in Christ Jesus, and that certainty was of greater value than all the rest.

2) We must adore Christ, beyond the awareness of our own imperfections or limitations or failures or uncertainties; we strain forward, we press on, we cling to him; we forget our past achievements and our past failures alike; we know that our destiny is worship—the glad and rich and fully satisfying enjoyment of God’s wonderful presence and overwhelming beauty in the company of all his people. Mary’s action was pure adoration, a glad and reckless embrace of Jesus Christ with no other “purpose” than love, thanksgiving, worship.

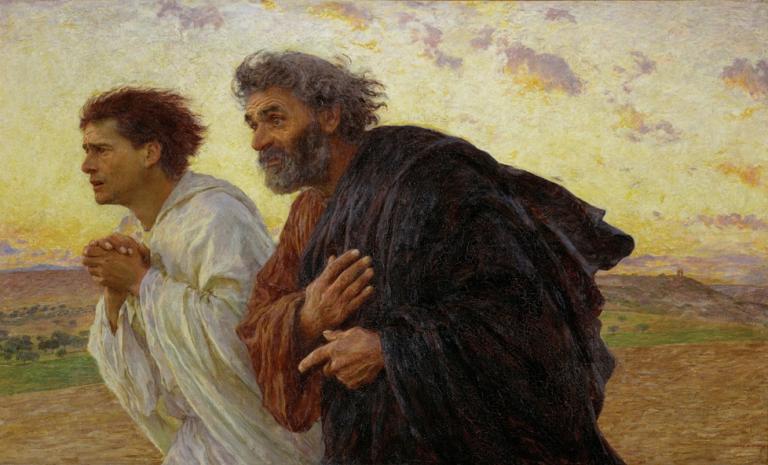

Apostles Peter and John hurry to the tomb on the morning of the Resurrection, Eugène Burnand , 1898;

We close with late 19th-century artist Eugène Burnand’s image, which joins all these ideas together in one passionate motion; John and Peter rush to the tomb—forgetting all their fear and sorrow and guilt and even their former hopes in their all-consuming longing for Christ. This is adoration and pressing forward and anticipating God’s new work. We too must push forward, strain toward the Crucifixion, which will be the death of all our calculating and maneuvering with God, and rush toward the Resurrection, which will be the presence of the One we love.

I didn’t give you the whole Augustine quote earlier, for he moves past the havoc of change; listen again as I add the last sentence: “I look forward, not to what lies ahead of me in this life and will surely pass away, but to my eternal goal. … You, my Father, are eternal. But I am divided between time gone by and time to come, and its course is a mystery to me. My thoughts, the intimate life of my soul, are torn this way and that in the havoc of change. Nonetheless, the memory of you stayed with me, and I had no doubt whatever whom I ought to cling to…”

Let the house of our souls, this house of our community, be filled with the fragrance of adoration… Amen.