“We’re saving it for the next generation, you know, after us, because it’s all disappearing”

So says Monique Brand, Executive Director of the Manitoba Association of Museums in The End of Our Memories, a documentary exploring the loss of community history that occurs as small museums in rural Canada struggle to remain viable. The documentary, which premiered this July at the Gimli Film Festival, was directed by Andy Blicq and produced by Huw Eirug for Manitoba Telecom Service’s Stories from Home project. It focuses on the story of those who work to preserve St. Malo Museum, but it also explores the larger struggle for survival of other small, local museums filled with community history and memories across the province.

Director Blicq sees the decline of these tiny sites of local history as a “bellwether” of a more general demographic shift in Canada: these museums begin to lose the fight against closure in a sort of proportion with the rate that former community members, particularly young people, leave their home towns to concentrate in urban centers. What they leave behind includes their hometowns, their elders, and what the documentary suggests is ultimately most devastating, them memories of the places and people who remained in more rural locations.

You might find it odd that reading the words of those dedicated to preserving the memories of their hometowns in what looks to be a losing battle would bring me almost to tears; yet I too know what it is like to carry memories. My grandfather did as well. You see, my grandfather was the youngest of his siblings and had a terrific memory. He knew the stories of his family, the stories of my grandmother’s family, and the stories of their childhood. And he told me and my sister and cousins these stories. Over and over on car trips to the mountains, I remember begging him to tell us once again about “the juggler who got the gold” and “the Fightin’ Five basketball game” and “when the Gypsies and Okies came to town” (he still used the slang of his childhood).

He told me how when he was nine, Selma, a small farming town in the Central Valley of California, got its first traffic light. During that summer, he and his friends would hitchhike the 8 miles out to it, and spend the day hiding on the side of the road. You see, back then the light sensors responded to weight, and so when they saw a car coming, they would run to the right hand cross street and jump hard on the weighted sensor, to ensure that the approaching car had to stop. Then they would run away, laughing as the driver was forced to wait for the slow changing light.

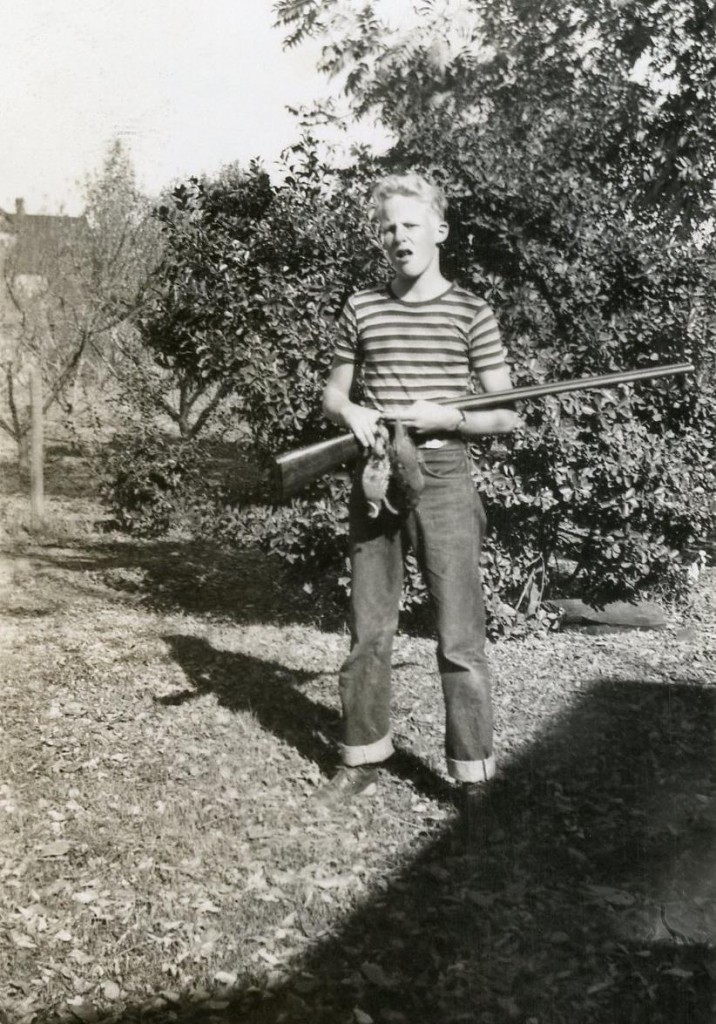

He told me about working on ranches, about fishing in canals, about losing his shoe hitchhiking to the mountains with his brother, about how his mother-in-law, Jo, always claimed to have seen a U.F.O. and how Jo had been a ballerina before meeting my Pops. How one boy from Kingsburg had gone home with his parents to Japan before WWII, and when the U.S. entered Japan, the boy was found by a Kingsburg soldier in a P.O.W. camp the U.S. soldier was assigned to. It turns out that the Japanese boy had been impressed into the Japanese army. Stories of place and history and community, how people can be formed by those and how that formation can transcend all of those because of people.

My grandfather died two years ago this fall. He was the best man I have ever known for reasons too numerous to list here; one of those reasons was that he taught me my history, my community, the world that built me. Years ago, my family convinced him to record his stories, and we had them transcribed. In his will, he left me the recordings and transcriptions with the instructions to publish them. I’m not yet at the point where I can read them without crying, much less listen to the cassettes, but what he gave me wasn’t simply recordings or papers, what he gave me was my history, our Valley’s history. He gave me memories that are not only his, so that others might know about their world, that others might develop what I termed last week a “habit of being in.”

For those of us in our twenties and thirties, especially, as we move and the world “globalizes” and what not, it is vital that we strive to preserve the history of our home communities and the communities we find ourselves living near and in. In The End of Our Memories, St. Malo Museum’s last board member, Edmée Gosselin, notes sadly that we have a culture that is just “not as interested in the history of communities.” Gosselin’s best solution, sending the museum’s collection to other museums, is not a true one as it continues the displacement of community memories away from the community which gave rise to them.

CityLab writer Ellie Anzilotti suggests, despite this disturbing trend, that community memories are not without those who fight to preserve them: Arborg and District Multicultural Village collects historical buildings from the community and moves those buildings to their District Multicultural Village, a 13 acre plot at the edge of town, where the buildings can be preserved.

In my own town, I volunteer at the San Joaquin River Parkway and Conservation Trust on weekends, where we maintain a historical museum as well as work to preserve local ecosystems in a sustainable way. The Parkway Trust invites the community to come together for local literature readings, music, nature walks, events, and even canoe trips. And, while the age skews older, there are millennials in the organization like Finn Telles, Director of Business Development, who have a passion for preserving the local history and environment.

For myself, my favorite days are when, while volunteering, visitors come up and begin to tell me about what they remember of the Valley from their own lives. Hiking along the river as children. Trips their family took. Fresno before central air conditioning. These stories are always fascinating and personal, yet they reach beyond the storytellers, and the more I hear these stories the more they, and the place that roots all these stories, shape me. A place can inform us, can impress itself onto us, but a place without history cannot give us a rooted habit of being in.

If we want to be present to the community we live in, if we want to begin to rebuild and strengthen our local communities, we need to know the stories that connect us to these places, the stories that let us reach beyond the limits set by generations. So,start by calling your grandparents. Then go to a local historical museum or veterans event. Ask questions and listen to the stories your questions evoke. And treasure those stories in your heart; let them shape you, form you, connect you, root you. Develop a habit not simply of moving beyond, but of being in. Wherever it is you may be.