Marilyn Matevia is an administrative assistant in the bishop’s office of the Northeastern Ohio Synod of the ELCA and a student in the TEEM program (Theological Education for Emerging Ministries.) She recently took a preaching class with me where she learned to use a “dialogical lens” in reading scripture and sermons. As she prepared this sermon on Luke 12:49-59, she discerned that sometimes following Jesus means NOT being neutral. [You can learn more about the dialogical lens in my book Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide.]

Notice how her sermon models prophetic self-critique and invites conversation. You can also watch a video of her sermon here. Take note of her delivery style – engaging and disarming; diplomatic yet firm; courageous yet humble. She preached this sermon on August 18, 2019, at Good Soil Lutheran Ministries in Rocky River, Ohio.

Sometimes Following Jesus Means NOT Being Neutral

by Marilyn Matevia

Some of you know that I work for the synod office – the regional outpost of the national ELCA. And maybe you also know that we recently concluded the annual synod assembly, our yearly gathering of voting members representing many of the congregations of our synod. One of my post-assembly chores is to summarize the feedback survey results and share them with the synod staff. Without fail, we get a handful of complaints from people when we have workshops or speakers who talk about justice. Of course, this being the church, and our guiding document being the Bible, most of our workshops and speakers will eventually mention justice in some form.

We probably each have a different interpretation of what “justice” means (it’s kind of an inkblot indicator of our own beliefs). But our assembly speakers and workshop leaders get specific. They might talk about our Christian duty to treat refugees with dignity. Or maybe they’ll talk about the millions of people in the United States (and the billions around the world) who are not getting enough to eat. Perhaps they talk about how sources of air and water pollution tend to concentrate near our lower-income communities.

All of these topics have something in common, which is… injustice.

They share in common a systemic failure to treat all human beings fairly, and with compassion and dignity. (Sometimes speakers get extra-radical and talk about how we treat other animals and the environment, too, but let’s just concentrate on the human element for now.)

What do you think our survey respondents say when they complain about these topics? Maybe some of you are thinking it right now, your very selves.

They complain that the speakers, or topics, are … “too political.” Or that they are showing a “political bias.”

I’m going to go out on a limb here and ask a question. Should Christians not have a “bias” about hunger? Is it possible to be neutral about starvation? For that matter, is it possible to be neutral about – say – lead pollution in public housing, or race- or sex-based wage differences, or indefinite detentions in overcrowded cages?

Staking a “neutral” stance on these issues ironically reveals a different kind of bias. One that is uncomfortable to admit. It’s a bias that assumes some people are more valuable than others, and some are more deserving of misfortune and mistreatment than others.

I thought about my own biases when I read our Gospel lesson this week.

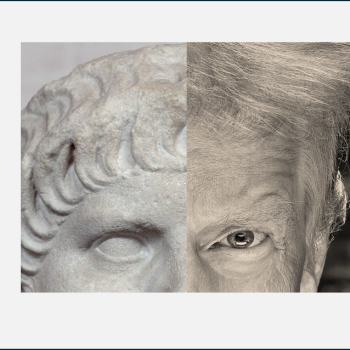

One in particular came to mind: my image of Jesus as kind of a peacenik. I have a tendency to picture Jesus as a peace-loving, soft-spoken teacher with a sheen of hallowed light around him bathing everyone in his gentle, loving presence. That’s not what we see in this passage.

For a little background on this text, it’s good to call to mind the state of the world when Jesus was walking it. The vast majority of the Palestinian population – his people – were poor or working class. 70 percent, according to one study.[1] 1 in 10 people were in constant danger of starvation. Slavery was rampant. Some slaves were prisoners of war, others were prisoners of debt, who sold themselves to work off what they owed.

This was the world in which Jesus launched his ministry – bringing good news to the poor, freedom to captives, sight to the blind, and proclaiming the year of the Lord’s favor.[2]

Those aren’t my words, of course – those are Luke’s, from earlier in the book – chapter 4. And importantly the phrase “year of the Lord’s favor” typically refers to the jubilee – when (every 50 years) debts are forgiven, prisoners are freed, farm fields and animals are allowed to rest, and the fruits of labor are shared.

Here comes Jesus, promising RELIEF from all these forms of oppression – once in a lifetime relief, once for ALL time relief.

But that new world won’t come easily. As Jesus says in Luke’s account: “I have come to bring fire on the earth… Do you think I came to bring peace…? No, I tell you, but division.” That kind of dramatic change will take a refining, purifying fire. Luke said so earlier in his gospel, putting the words in the mouth of John the Baptist.

Jesus brings a refining, purifying fire that burns away the social orders and habits and practices that create permanent injustice, permanent unfairness.

And it will cause divisions: pitting a new vision against an old, fossilized one. Dividing those who cling to and benefit from the old power structures from those who want to usher in the new order, the kingdom of God. Pitting – as Jesus says – father against son, mother against daughter…

Heavens to mergatroid, as my grandmother would say. Why would Jesus say something so contentious? So divisive?

Where is my patient, gentle, peacenik Jesus?

This text challenges my bias about Jesus, and about what it means to “go and do likewise!”[3] – as Luke says elsewhere in this gospel.

Well, if we sat together and studied the gospel of Luke, start to finish, we would be reminded that Luke sees Jesus as the agent of God’s justice.[4] And that Luke understands justice in tangibles, like how society treats the vulnerable and handles money. And how society awards status and access. No murky inkblot prints here; he’s very specific.

We would also see that Luke believes certain things get in the way of following Jesus: wealth, status, fear. And, I would add, an unwillingness to wrestle with these difficult issues.[5] So he very clearly links following Jesus with doing justice.

And sometimes – maybe most of the time – following Jesus means not being neutral.

The Benedictine sister Joan Chittister has a new book out, called The Time is Now. In it she writes powerful words.

Yes, the Christian ideal is personal goodness, of course, but personal goodness requires that we be more than pious, more than faithful to the system, more than mere card-carrying members of the Christian community. (Our faith demands), as well, that we each be so much a prophetic presence / that our corner of the world becomes a better place because we have been there.[6]

Well, that’s kind of intimidating. She’s asking for prophets and there’s nobody here but us chickens. (Pun intended.)

But Jesus brought the hammer down in those last few verses of our text. I’m paraphrasing, but he basically says, “You know how to read the clouds to predict weather. You do it all the time. You’re smart and observant. Yet you act like you don’t know what is just and what is unjust, or how to DO justice. Do what you know is right.”

This means that I have to let go of my bias. I have to NOT be neutral.

There is only one sense in which a topic like this is “political.” The word comes from the Greek term, polis, which is basically a gathering of people. It’s a community – a city and its citizens. As the Catholic priest Father Michael Marsh wrote in a sermon several years ago, the “most basic concern (of politics) is …the ordering of relationships. It’s about the way we live together and how we get along. It’s about people. (And) Those concerns are central to the practice of Christianity.” He says, “We believe that God has something to say about how we live and the way we relate to one another. …

“In that regard, the incarnation (itself), the embodiment of God in humanity, is a deeply profound political statement.”

What might it look like for us to wrestle with these questions? To release our bias? To let go of our quiet, gentle Jesus and follow the Jesus of justice?

In churchwide workshops they often teach a group exercise called “asset mapping.” This involves figuring out what resources and talents or skill sets an organization has and how they might address some congregational or community need. Our church can do this together. We can read the signs of the times, read the clouds, read and watch the news. We can talk to neighbors to figure out what’s needed, and what we can bring to fill the need. Maybe you already have your own suggestions for how we might address these needs. We could talk about them today, over coffee, after the service.

But if you’re like me, you may also squirm a little when you think about our little church addressing these needs.

So we should ask ourselves: what makes us uncomfortable? What are we UNWILLING to do or be? And why are we unwilling? We need to really needle ourselves about the “why.” Are the reasons practical? Logistical? Financial? Emotional? I’m talking to myself right now.

A friend of mine from grad school was arrested a few weeks ago. She was NOT being neutral! She was one of 70 Catholic peace activists arrested in the Senate building in Washington DC for “unlawfully demonstrating” against the mistreatment of migrants and asylum-seekers in immigration detention centers. I’m asking myself: would I be willing to go that far? And if not, WHY not? What could be more important than insisting on compassion and dignity for my fellow human beings?

The gospel of Luke makes this point clear, through his account of Jesus’s ministry:

No one is outside the scope of God’s justice.[8]

But it will take work – sometimes difficult and disruptive work – to get everybody in. Jesus empowers his followers – then and now – to envision a different reality. This new reality is what we call the kingdom of God. And when we envision it, when we can see it, then we can build it, right here in our corner of the world.

So be it. Amen.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Read also:

A Fiery, Divisive Jesus? Luke 12:49-56 Through a Dialogical Lens

Using a Dialogical Lens for Scripture and Preaching

[1] “Introducing Luke,” by Babu Immanuel Vankataraman, God’s Justice: the Flourishing of Creation and the Destruction of Evil (NIV Study Bible, Zondervan, 2016), 1441.

[2] Luke 4:18-21

[3] Luke 10:37, NRSV

[4] Vankataraman, 1442.

[5] Shoot… I think this insight comes from Matt Skinner’s column on the text; I will try to relocate.

[6] Joan Chittister, The Time is Now: A Call to Uncommon Courage (Convergent, 2019), 27. She used the phrase “Christianity requires.” I Lutheranized it.

[7] https://interruptingthesilence.com/2016/01/25/the-politics-of-jesus-a-sermon-on-luke-414-21/; parenthetical additions mine.

[8] NIV God’s Justice, 1441.