The parable about the Unforgiving Servant shows us that forgiveness is essential – but so is accountability.

My friend and faculty colleague, Emily Askew, is a theologian who used to volunteer for a domestic violence center. The stories she tells me of women who are abused by their husbands, boyfriends, or family members are horrible enough. What’s worse is when the women tell about pastors who urge them to stay with their abuser and “forgive them.” And they use the Bible to rationalize their twisted, sadistic view of forgiveness.

Matthew 18:21-35 is one of those passages used to manipulate abused and oppressed people into extending “forgiveness.”

They say: “See, Jesus says right here, you must forgive seventy times seven times. The parable is clear – if you don’t forgive, you yourself will be tortured by God.” As a result, countless women have been silenced, subjected to even more violence, and even murdered.

So, is this what Jesus intended when he told this parable of the unforgiving servant? Is this what Matthew wanted when he put Jesus’s teaching into his Gospel? To rationalize someone going back to their abuser again and again?

Certainly not.

So let’s take a minute to unpack what’s going on in this passage, so we can understand why it mattered for Matthew’s church, and how we can avoid misinterpreting it today. Because, as Emily often tells her students:

Theology matters. How we read the Bible matters. It is literally a matter of life and death.

The original audience for Matthew’s Gospel was Jewish Christians. There were tensions within the Matthean church between members who were hurting each other. So Peter’s question to Jesus was on the hearts and minds of Matthew’s church – how often should I forgive someone who sins against me?

Remember, this reading comes on the heels of the previous verses in which Jesus explains the process of dealing with conflict in the church. When someone sins against you, he says, try talking it out one-on-one. If that doesn’t work, bring in a neutral third party. If that fails, you’re going to have to take it to the larger governing body within the church.

Verses 18-35 continue the idea of this process for dealing with conflict, sin, and pain in relationships. Peter probably thought he was getting the gold star by suggesting that he should forgive someone seven times. Seven is the number for completeness in the Bible.

But Jesus expands the notion of forgiveness on orders of magnitude that probably shocked Peter and Matthew’s church. There are two translations: one says seventy-seven times, which is a lot. The other is seven times seventy, which is 490 times!

You may think this is excessive. How can we be expected to forgive that much?

Well, when you are in a relationship with someone – whether it’s your spouse, or a friend, or your fellow church members – forgiveness is an ongoing process and is often required many, many times.

Here’s an important thing to understand. In this passage, the assumption on the part of Jesus, and thus Matthew, is that these relationships are already built on a foundation of good faith. They have the best intentions of living together as a community of Christ. But Jesus, and thus Matthew, also recognize that we are sinful humans. We are sometimes selfish, petty, annoying, greedy, and frustratingly wicked. We hurt each other “in thought, word, and deed, by why we have done and by what we have left undone,” as we say in our rite of confession.

So, Matthew has Jesus explain to his disciples (and thus his church members) how to stay in relationship after there has been hurt and damage. And he does this by telling a parable about a king and one of his servants. We’ll call that servant “Fred.” The king finds out that Fred owes him an enormous debt – ten thousand talents. This is no small sum. It’s like the debt of a small country.

Now the original readers of the gospel would have known that no one person could have accrued that level of debt. It’s a ridiculously huge sum. So they would have recognized the hyperbole of this astronomical debt.

But they would have been shocked by the astronomical mercy of the king who forgives the whole debt! The point of this parable is to show what divine forgiveness looks like in a way that upends our expectations.

Now, it would have been fine if the parable ended with the Fred’s debt forgiven and they all live happily ever after. But Jesus adds a disturbing twist. On his way out of the palace, Fred encounters another guy, whom we’ll call Dan. This guy owes Fred money. And it’s not a small amount – about $7,000 dollars.

You would think that Fred – who had just been forgiven the debt of a small country would remember how it feels to be relieved of this burden. You would think he’d want to pay it forward, if you will, and extend the same mercy to Dan. But no. He grabs him by the throat, choking him with anger.

When Dan pleads with him, “Have patience with me, and I will pay you,” you would think Fred would have remembered saying these exact same words to the king just a few minutes earlier. But no. He throws Dan in debtors’ prison.

The rest of the servants run to tell the king what has happened. And he explodes in rage. “You wicked slave! I forgave you all that debt because you pleaded with me. Should you not have had mercy on your fellow-slave, as I had mercy on you?” And he hands Fred over to be tortured until he pays the entire debt.

Frankly, it would have been fine if the parable ended there as well. Of course, there’s no happily ever after, but at least there’s justice.

And yet, Jesus throws in one more twist. He says, “So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”

Gulp!

Our happy ending has turned into a dismal, painful, scary ending. What does this mean? Is God vengeful and merciless after all? Why is Jesus threatening the disciples with God’s wrath if they don’t forgive? And does this mean that pastors can use this text to browbeat people who have been abused, sending them back with the fear that God will torture them if they don’t forgive their abuser?

Absolutely not! Here’s what such pastors conveniently overlook in this parable and Jesus’s teaching.

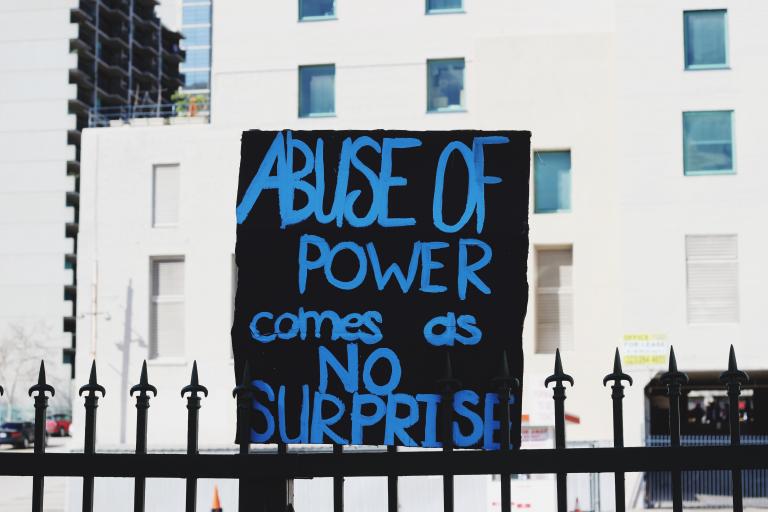

We have to factor in the dynamics of power when it comes to forgiveness.

In this parable there is vertical power and horizontal power. The king has vertical power. He is above everyone. But Fred and Dan start off with horizontal power; they are on equal footing since they are fellow servants. That changes, however, when Dan owes Fred a debt. Fred becomes the one with the power – power to have Dan thrown in prison and lose everything.

Notice what happens in this parable. Both servants acknowledge that they are in the wrong. And did you notice – they do not actually ask for forgiveness. They ask for time to make it right.

“We confess that we are in bondage to sin and cannot free ourselves.”

Fred gets something he doesn’t deserve – forgiveness of the debt. The king has used his power to restore the relationship, to make sure Fred is not separated from his family and stripped of his home and possessions.

But Fred does just the opposite with Dan. He uses his power over Dan to destroy not just their relationship, but to take away everything – including his freedom.

There is an hypocrisy to Fred’s actions that the king cannot fathom. The king cared enough about Fred to make sure he didn’t lose his freedom, his possessions, or his family. But Fred refused to care enough about Dan to extend to him the same mercy. This means that Fred abused his power. And the king will not tolerate that.

This is why it is not just biblically incorrect, but morally repugnant to use a story like this to convince an abused person – or an entire race, or even an entire nation – to just “forgive and forget” when there has been an abuse of power.

We cannot use this passage as a means by which to shame those who have been subjected to violence and injustice by those with power. Whether it’s a situation of domestic abuse, misogyny, racism, xenophobia, economic servitude. Or pastors who abuse their power. Or lies told to cover up the truth about a deadly virus. We cannot use the Bible to excuse the abuse of power. And we cannot use scripture to silence those seeking justice.

Remember the power differential here – it’s the one who has the power who is expected to extend mercy. When Dan is thrown in jail, the king doesn’t go to him and say: “Ah, you must forgive Fred, the one who had you thrown in jail.” No, his retribution is for the one who abused his power. Even after the king had demonstrated the correct way to use one’s power – with mercy and forgiveness. – Fred tossed this aside for his own gain.

Jesus tells this parable to warn the disciples (and the Matthean church) about what they will end up with should the system of mercy fail and processes of forgiveness break down.

This parable is meant to shake us awake to realize what happens when people abuse their power and refuse to practice the divine reciprocity of mercy.

So, given the astronomical breakdown in our political system, in our governmental institutions, in our democracy, in certain families and relationships – what can we learn from this parable? What is the church’s role in teaching about forgiveness and the consequences of abusive power?

As we are consumed in “outrage culture” that stokes fires of revenge to the point of violence, how can the church speak a prophetic truth about both mercy and accountability? What kind of church shall we be, knowing what this passage models for us? Knowing what challenges our community is facing in the lead-up to the election? Knowing that law enforcement officers continue to abuse their power across the country? And that after hundreds of years, there is still no accountability around systemic racism that churning our communities with righteous anger?

What shall we say as a church when a president flouts God’s expectations for those in power? And unapologetically stokes divisiveness, lies to cover up his crimes, and creates policies that have led to the deaths of tens of thousands of people and the crumbling of a democracy?

What do we say to the abused when the abuser is in cahoots with religious leaders who twist and manipulate the Word of God to protect their sadistic grip on power?

We say this:

Our God is a God of relationship who wants the church and all people to practice mercy, generosity, forgiveness, and kindness. And God holds accountable those who abuse their power, who prey on the weak, and who care about nothing but themselves.

The church needs to point to this parable and remind those who are abusing their power that they had better change their ways, or there will be nothing but anger and pain. Failing to extend mercy leads to a breakdown in the entire system.

What we must emphasize are the common values that must undergird our society, and our church, and our relationships: respect, mercy, forgiveness, and the reciprocity of grace.

In this parable the whole system breaks down. Everyone ends up either angry, imprisoned, or tortured. Those are the results when mercy is choked of air and the precious gift of forgiveness is tossed aside like a dirty rag.

This parable describes the consequences when the reciprocity of mercy fails. It’s supposed to prick us with awareness that things need to change.

I would like to imagine that Peter began to change when he heard this parable. Seventy times seven. I’d like to imagine that he became more forgiving of his fellow disciples. Seventy times seven. I’d like to imagine that Peter remembered this parable when Jesus forgave him for denying his rabbi during the trial and crucifixion.

Seventy times seven.

I’d like to imagine that the members of Matthew’s church decided to practice both accountability of power and the reciprocity of mercy, paying grace forward. Seventy times seven.

And I’d like to imagine that our church can think deeply about what it means to be in relationship with each other, with those who exercise power, and with those who have had their power stripped from them.

Because theology does matter. How we read the Bible does matter. It is literally a matter of life and death. And the church needs to proclaim God’s radical forgiveness and divine mercy, as well as the surety of God’s accountability and justice.

Other posts about forgiveness:

We Will NEVER Forgive You: Greta Thunberg, Climate, and the Unforgivable Sin

Will God Forgive Us? ‘First Reformed’ Film Review

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is also the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/