Climate migration connects the stories of Jacob, Joseph, Jesus, Jorge and Rodrigo. How should Christians and the church respond?

Scripture readings:

Genesis 41:53 – 42:5 (Jacob sends his sons to Egypt to buy grain during a famine)

Luke 9:51-58 (Jesus laments that “the Son of Man has no place to lay his head”)

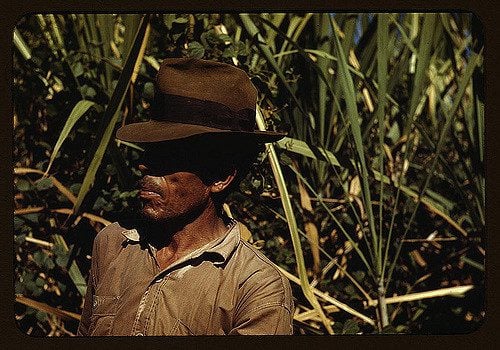

The old man kneels down onto the hard, crumbling soil beneath his feet.

His bony fingers caress a stalk that should be green and full of grain but instead snaps and frays into brittle, brown sinews. His knees creak as he stands up, his eyes scanning the withered fields around him. Feelings of failure and despair well up in his chest.

What has caused the land to do this?

Did they not find favor with God? Were they being punished? It felt like there were forces much bigger than him and his family that were pushing them away from this land.

He had tried so hard for so many years to make this work. But the drought just would not relent. He would need to send his family away from this land that they loved.

He heard that there was a country far away where there was plenty of food. This is where they would go. But what would they face on the journey? Would they even survive? Would they be welcomed when they arrive in that new land?

He reaches down and picks up a handful of the dry, dusty dirt. He weeps a prayer as the wind whips at his teary face, scattering the dirt from his hands.

********

Are you wondering who this man is?

His name could be Jacob, and his story could be as old as Genesis. This could be a scene from the saga about Joseph and his brothers and father Jacob in the lands of Canaan and Egypt. That is a story where a massive drought drove the desperate migration of people away from their land seeking survival in another.

But the man in this story is one we will call “Rodrigo,” and his story is happening now.

This is one scene in the saga of climate failure in hot zones across the world that is driving millions of desperate people to leave their homelands seeking some way to survive.

According to a New York Times Magazine article by Abrahm Lustgarten, Guatemala, the country where Rodrigo lives, is expected to see a decrease in rainfall “by 60 percent in some parts of the country, and the amount of water replenishing streams and keeping soil moist will drop by as much as 83 percent.” Researchers project that by 2070, yields of some staple crops in the state where Rodrigo lives will decline by nearly a third. Like so many other countries in Central America, “Half the children are chronically hungry, and many are short for their age, with weak bones and bloated bellies.” https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/23/magazine/climate-migration.html

For his part, Rodrigo pawned his last four goats for money so that his son Jorge and his 7-year-old grandson could pay the coyote to take them north to America.

Jorge’s wife stayed behind with their two younger children, not knowing what the future will hold for them or for her husband and oldest son.

If this was Jacob’s story, we would know the outcome.

His sons make the perilous journey to Egypt to purchase grain so that their tribe will not die of starvation. There is a chapters-long drama recounting their brother, Joseph, testing the men to see if they had changed from their earlier days when they had sold him into slavery. In a God-guided turn of events, Joseph rises from wrongful imprisonment to become the head of Egypt’s economy. Years later, in the midst of a drought that devastates the land, he eventually reconciles with his brothers and allows their whole tribe to migrate to Egypt and resettle there.

But Jorge and his son will likely face a far different outcome.

There is no guarantee that they will survive the journey across wilderness landscapes with very little access to food, water, places to rest, or medical care for any injuries. They will face threats from violent assaults along the way. And when they finally reach the border where they hope to find “Egypt’s bread,” they will not be welcomed. This will not be a nation where a benevolent political leader or government official will set aside land for them to live and rebuild their lives.

No, in this country, they will be put into detention centers and treated like criminals, possibly separating father from son.

They will not be able to apply for asylum due to climate disasters because that is not recognized as a reason for seeking protected status. So there is a chance they will be turned away.

Even if they are allowed to enter this country, they will need to go through a complicated process of seeking a sponsor who will help them find somewhere to live, a job, a place for the boy to go to school. They will have to learn a new language. And they will likely face hostility from the people in the town where they will eventually settle.

Maybe it will be your town or city.

Maybe your own neighbors will look at Jorge with suspicion and complain that he doesn’t speak English. Perhaps your own children or grandchildren will pass Jorge’s son in the hallway at school where their peers call him names and shove him against the cold metal lockers.

Maybe you yourself will have difficulty getting the nasty epithets out of your mind when you watch Jorge ring up your cup of coffee at the Quikmart. Coffee that would have come from his own land back in Guatemala if the drought had not ravaged his crops. And the hurricane before that. And the flood before that.

Or maybe you will never see Jorge at all because he works nights at the meat-packing plant making less money than you pay your kids’ babysitter. Or because he works in the orchard fields of an agro-conglomerate that does not supply him with protective equipment when it sprays pesticides and herbicides. And when he stands in these fields, his skin and lungs burn as he thinks about his father Rodrigo picking the few kernels from shriveled cobs of their own fields back home.

Or maybe . . . when you see Jorge you will remember that you are a Christian.

And you will recall the words of the man Jesus Christ whom you worship. Jesus said, ‘Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.’

Just like Jorge and his son, who made the perilous journey over weeks, perhaps even months, and found nowhere to safely lay their heads. In that single sentence, Jesus aligns himself with those who have no home, no safety, no rest for their weary bodies. Jesus, whose parents fled with him when he was just a baby seeking refuge in a foreign land – Egypt. Just like their ancestor Jacob and his tribe had sought safety in Egypt generations before.

Jacob may have asked the very same questions that Jorge and his father Rodrigo asked.

What has caused their land to fail? Did they not find favor with God? Were they being punished? It felt like there were forces much bigger than them pushing their family away from this land.

But here is where Jacob’s story and Rodrigo and Jorge’s story diverge. Those forces driving them from their land are not because of God’s punishing hand. Ironically, those forces originate in the very country where they are now seeking refuge. This country – the United States of America – which has burned so much fossil fuel over the last two hundred years that, together with other developed nations, has blanketed the earth’s atmosphere with heat-trapping greenhouse gases. This is resulting in hot zones along the equator, making them unlivable for millions of people.

You see, climate change is what’s known as a “threat multiplier.”

Cameron Ramey, writing for the Yale Program on Climate Communication, explains that in Central America, “Since 2014, a series of droughts have wrecked the region’s harvest, forcing almost one-third of its people into food insecurity. In Honduras, the changing climate likely contributed to the 2018 drought that wiped out over 80% of maize and bean crops. Failing harvests and increasingly destructive weather events have exacerbated migration in this region by escalating hunger, poverty, and violence.” (https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/news-events/climate-migration-needs-personal-stories/)

But this is not what most of us think about when we hear that a “migrant caravan” is coming up through Mexico to our southern border.

Most of us hear voices from screens warning us that these are lazy, no-good, criminals and job-stealers who will take what is ours and suck off our economy. Never mind that it is our economy that is both exploiting and destroying the countries from which these people are coming in the first place.

So we return to Rodrigo’s weeping prayer carried on the wind that scatters the parched soil in his hand.

We must ask, how can we as Christians, as churches, be part of God’s answer to that prayer?

What is our role in this story? This saga unwittingly finds us as not the heroes, but as the antagonists. We are the ones who have contributed to the conditions that drive Jorge and millions like him to our borders. We have benefited from the burning of fossil fuels while largely avoiding the costs. What is the church’s response to this?

Several our denominations and many people of faith are already thinking about how best to prepare for the immigrants who will be seeking refuge in this country this year and in the decades to come. They are sharing stories of people like Rodrigo and Jorge that “give a human face to one of the most tangible consequences of unmitigated climate change that we face today.” https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/news-events/climate-migration-needs-personal-stories/

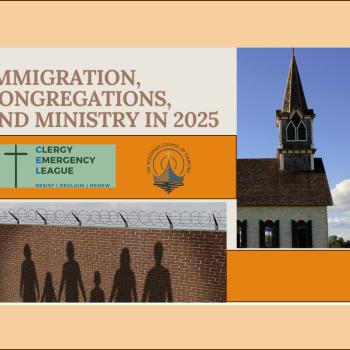

I want to challenge churches and Christians to go even deeper and broader by expanding their ministry to advocate for climate migrants who are suffering the effects of multiple environmental, economic, and societal crises.

You can do this by helping to educate people about the urgency that is driving families to our communities from these climate-ravaged countries. And why it’s necessary that they must leave their home countries, even when they want nothing more than to stay. And why it’s necessary to change our immigration system so that climate is factored into their legal ability to seek asylum.

As PBS Newshour writer, Miranda Cady Hallett explains, “In the absence of coordinated action on the part of the global community to mitigate ecological instability and recognize the plight of displaced people, there’s a risk of what some have called ‘climate apartheid.’ In this scenario – climate change combined with closed borders and few migration pathways – millions of people would be forced to choose between increasingly insecure livelihoods and the perils of unauthorized migration.” https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-climate-change-is-driving-emigration-from-central-america

Organizations like Asylum Seeker Sponsorship Project and some denominations have programs to help Christians and congregations become sponsors of these immigrants, which vastly increases their chance of being allowed entrance into the country. Even more important is providing support when they arrive, helping them find employment, helping them learn English, helping them feel welcome in their new communities.

I want to stress that this is not about Christian charity.

We need to understand the part we, in this industrialized nation, have played in the inequality, injustice, and climate pollution that has contributed to the conditions that require people to have to emigrate from their lands. Certainly, our participation in this domination system is unwitting and unintentional. But while these immigrants have no choice in what has happened to them, we have a plethora of choices about how we can respond to the needs of others we helped create.

So these efforts aren’t charity or even solidarity. They are part of our efforts of repentance, restoration, and reparations. Our Christian responsibility is to help to right these wrongs, especially when we have helped to create them.

We as Christians and as congregations have a chance to reshape Rodrigo and Jorge’s story. We can’t make it a happy ending. But we can help make their story a little less painful, to ease the suffering to which we ourselves have contributed. We have a chance to make amends. To help the trajectory of this story bend toward justice instead of snapping and fraying into brittle, brown sinews of empty stalks in empty fields.

We can help lift up Rodrigo and point north to where his son and grandson have found a community that welcomes them. Where congregations like yours are doing everything they can to help mitigate the climate crisis and actively engage environmental justice issues. Where Jorge has found work that enables him to send home money for their family left behind.

So that maybe the feelings that well up in Rodrigo’s chest are not just failure and despair, but relief and hope.

Hope that comes from the God of Jacob, Joseph, and his brothers to reconcile over bread in a foreign land. Hope that comes from a Savior who knew what it meant to sojourn in a wilderness, to seek refuge from violence, to have no home to lay his head.

We can cup our hands to catch those tear-stained prayers carried on the dusty wind.

Amen.

Read also:

Is Earth Worth Dying For? A Reflection on the Earth Martyrs

When Earth Demands Sabbath: Learning from the Coronavirus Pandemic

Noah’s Ark and Climate Change: What Kind of Church Will We Be?

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her latest book, co-written with Jerry Sumney is Apocalypse When?: A Guide to Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2020).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/