The Bible is filled with stories of people engaging in faithful dialogue about the contemporary issues of their time. These stories can help us engage the difficult conversations of our own time. Mark 13:1-8 which recounts Jesus’s dialogue with his disciples foretelling the fall of the Temple is especially relevant for us today.

In Chapter Four of my book Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), I suggest 6 steps for using the dialogical lens for reading and preaching scripture [which you can read about here]. The dialogical lens yields important insights about Mark 13:1-8, which I’ll share below.

Six Steps for Using the Dialogical Lens

- Point out the dialogical aspects of the passage.

- Determine what’s at stake.

- Identify the values.

- Explain how God, Jesus, and/or the Holy Spirit is active.

- Recognize what the dialogue is teaching us.

- Suggest possible next steps.

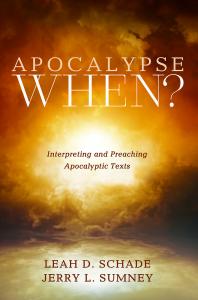

For this text, I’m drawing on the exegetical work of my colleague, Dr. Jerry Sumney, professor of biblical studies at Lexington Theological Seminary. You can read more in the book we co-authored, Apocalypse When: Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts. See chapter 4 where we suggest constructive ways to engage the apocalyptic aspects of Mark 13.

Here’s an outline for applying the dialogical lens to Mark 13:1-8, the story of Jesus foretelling the destruction of the temple.

1- Point out the dialogical aspects of the passage.

The author of Mark (specific identity unknown) wrote this Gospel at least 30 years after Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection – a generation after the original events. His original audience was likely a mix of Jewish and Gentile believers living with various degrees of persecution within the Roman Empire. This dialogue between Jesus and his disciples takes place against the backdrop of the Temple. But Mark’s congregation has already seen the Temple fall. (Note, also, that the lectionary pairs this text with Daniel 12:1-3, also an apocalyptic book which refers to “a time of anguish” in v. 1.)

The characters in this story are Jesus and the disciples, specifically Peter, James, John, and Andrew. But it’s likely that Jesus’s words about the Temple were also overheard by the crowd. Perhaps even the religious leaders of the Council were present, since they later falsely accuse him of threatening to destroy the temple (Mark 14:58, 15:29).

2 – Determine what’s at stake.

in Mark 13:1-8, Jesus is preparing his disciples for the upheaval to come. But the disciples are concerned about the occurrence of these predicted events. They are worried about their safety and their ministry with Jesus. Yet for Mark’s congregation, the attack by Rome and the fall of the temple has already happened and was a traumatic event for both Jewish and Gentile church members.

They all have similar questions. What are they to think when this temple is destroyed? Does it mean their God is not as powerful as they thought? What could this mean about use of the Hebrew Scriptures, the only Bible they had? How could the God of the whole cosmos allow the one Temple dedicated to God to be overrun?

3 – Identify the values.

They (disciples and Mark’s church) cherished the sacred space of the Temple and mourn its loss. Also, they honor and venerate Jesus. And they are anticipating the eschaton, the return of Jesus.

Ideally, they could begin to understand that Jesus’s words (coupled with his “cleansing” of the temple) signal the end of the Temple system. As such, they can release their attachment to it. They all want to see a new world emerge, a new paradigm of justice built on the grace and justice of God, not just on stones that can be toppled. But letting go of sacred places is no easy task (ask any congregation dealing with building issues or possible closure!). History, sentimentality, and a theology of place are in tension with a Christ-centered theology independent of the Temple.

4 – Explain how God, Jesus, and/or the Holy Spirit is active.

As Jesus leaves the Temple for the last time, he engages the disciples in dialogue after they marvel at the size of the building. He tells them that this holy edifice will be destroyed. Of course, this causes the disciples consternation. But Mark intends this story to function as a source of encouragement for his readers who have already experienced the Temple’s fall. Why? Read on.

5 – Recognize what the dialogue is teaching us.

Like the church in Mark’s time, the church today is also beset by doubt, consternation, and insecurity. This is especially true given the extended pandemic, social unrest, conspiracy theories and disinformation, the climate crisis, and rising white supremacy. However, it should provide some comfort to us (as it was meant to comfort Mark’s congregation), that even before his death, Jesus knew these things were about to occur. What Mark wants us to understand is that these devastating events do not mean that God is absent or has abandoned us.

What can we learn about being faithful people who engage the conflicts and sin of the world while maintaining the commitment to grace, hope, and love? Even when we are afraid as we enter into highly-charged moments (as many dialogues can be), we can trust Jesus’s presence among us, assuring us not to fear.

How do we hear the voice of Jesus preparing us for upheavals and quelling our panic in the midst of our dialogues, our sacred exchanges, our holy discussions? Faithfulness means remaining steadfast with the teachings of Christ. These are what maintain the community of faith, not the impressive — but temporary — signs of power and strength. Like Jesus with the disciples, we can welcome an open, honest exchange about what truly constitutes our faith and our community. And we can expect to have our assumptions challenged. But we can also trust in the presence of Christ to help us endure in faith.

6 – Suggest possible next steps

Like Jesus and the disciples in Mark 13:1-8, and like Mark and his congregation, we have an opportunity to enter into “holy dialogue.” Can we be a church that engages the difficult but necessary conversations about what it means to listen to Jesus while existing in a moral/ethical paradigm that rewards conflict, war, and “kingdom rising against kingdom”? What does this mean for our society, our families and communities, and our congregation? How might the church function as a place that invites dialogue about these issues – the powers that benefit from stoking fears about “end times,” Armageddon, race wars, civil war, etc.?

Are we learning what not to do based on what we see in this text?

This story about Jesus predicting the temple’s fall admonishes us: don’t become enthralled by overt displays of power and strength. Also, don’t try to predict the time and place of the eschaton. And don’t lose hope when the temples fall.

So, what kind of church shall we be, knowing what the Bible models for us, and knowing what challenges our community is facing?

This text tells us that Jesus engages us in the shadow of our temples, the sites where we believe we encounter the divine. These temples might be our economic system, our churches, our privilege, our temporarily abled bodies, or our status.

So what can the church do to proclaim Jesus as the center and source of our moral ethics, even when temples fall, wars rage, and the earth quakes? How can we model basic decency and compassion? Caring for the vulnerable and protecting the weak? Honoring our neighbors and ministering with honesty in the midst of entities that thrive on chaos, sowing discontent, and “nation rising against nation”?

As you and your congregation wrestle with these questions, know this. Ultimately, there is a power that is greater than our religious systems (symbolized by the Temple). It’s longer lasting than the powers of evil (symbolized by the Roman empire). And it’s more effective than violence (Jesus’s crucifixion). It is the power of truth, honesty, discernment, advocating for and protecting the vulnerable, resisting authoritarian oppression, and casting a vision for the Realm of God.

This is what Jesus tells us standing beneath the towering temple. This is what Jesus’ ministry, life, death, and resurrection were about. And this is who God is, what God does, and what God wants to church to be about.

Read also:

Using a Dialogical Lens for Scripture and Preaching

Breach-Repairers: Preaching Isaiah 58 Using a Dialogical Lens

A Fiery, Divisive Jesus? Luke 12:49-56 Through a Dialogical Lens

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her latest book, co-written with Jerry Sumney is Apocalypse When?: A Guide to Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2020).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/