![John XXIII - by Gedoughty02 (Pope_Saint_John_Paul_XXIII.jpg) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/721/2016/07/Pope_Saint_John_Paul_XXIII-989x1024.jpg)

What broke the fourth wall was that Sam got a tenure-track assistant professorship at my alma mater, the University of British Columbia. No longer was Sam a smart, if not renegade, Catholic guy working in the secular academy whom I read for fun; I was first introduced to him on Facebook, and then we finally met face to face, and in the process, he became a person to me.

I hate to tell people that I’ve actually learned things from Sam because it makes our friendship sound hierarchical; after all, Sam is a person, and I am a person. But by being a person and insisting that I am a person, Sam revealed to me quite early on one of Francis’s greatest secrets: he too is a person!

In probably the first thing that I read of Sam’s after we became friends, Sam explains that Francis is a person because he acts in relation to other persons in concrete situations, not out of an ideology. This is what we got, Sam says, when we got a Latin American pope. In this way, Sam has been teaching me more about Latin Catholicism than anyone else I know because his Latin Catholicism, like Francis’s, is a Latin American Catholicism. In turn, it turns out that ‘liberation theology’ is also not about ideology. For example, like everyone else at my alma mater, Sam teaches the book that all of his colleagues there love, Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, even organizing a whole conference about it, at which I got to present – on Hong Kong, no less! But what Sam does with Freire is to focus on what Freire calls ‘humanization’ as ‘the people’s vocation’ (p. 43). What is liberation in Freire? It is to free persons to be persons.

Isn’t this what Francis means by mercy? Certainly, this personal quality permeates Francis’s book for the Year of Mercy, The Name of God Is Mercy. In one striking moment, Francis tells the story of a single mother he met when he was a parish priest in Argentina. She was struggling so much economically that she had to resort to sex work to earn a living:

She was humble, she came to the parish church, and we tried to help her with Caritas (our charity). I remember one day–it was during the Christmas holidays–she came with her children to the College and asked for me. They called me and I went to greet her. She had come to thank me. I thought it was for the package of food from Caritas that we sent to her. “Did you receive it?” I asked. “Yes, yes, thank you for that, too. But I came here today to thank you because you because you never stopped calling me Señora.”

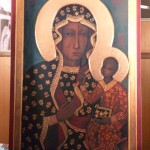

Francis treated her as a person; this is what mercy is. Or as Francis comments on this story, ‘Experiences like this teach you how important it is to welcome people delicately and not wound their dignity. For her, the fact that the parish priest continued to call her Señora, even though he probably knew how she led her life during the months when she could not work, was as important as — or perhaps even more important than — the concrete help that we gave her’ (p. 60). For Francis, this is what John XXIII meant when he called Vatican II with the words, ‘The Bride of Christ prefers to use the medicine of mercy rather than arm herself with the weapons of rigor’ (p. 6).

Francis is a person. Sam is a person. The Señora in this story is a person. And I am a person.

What is striking is how Orthodox this all is. Here’s Sam again.

In Sam’s book Folk Phenomenology, he says that there are two ways of looking at what it means to be a person. A Western approach focuses on the person’s legal autonomy. But an Eastern approach, one characterized by Orthodox theologian Christos Yannaras, breaks down the person in Greek to the word prosopon: ‘I have my face turned towards someone or something; I am opposite someone or something’ (Person and Eros, p. 293). ‘The whole human person for Yannaras, then, is,’ as Sam closes in for the kill, ‘all light, all face, all eye’ (Rocha, p. 99, emphasis his).

Or as Francis quotes ‘the beloved Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, with whom we share the hope of full ecclesial communion’ in Laudato Si’ (7), the environmental crisis requires

a change of humanity; otherwise we would be dealing merely with symptoms. He asks us to replace consumption with sacrifice, greed with generosity, wastefulness with a spirit of sharing, an asceticism which “entails learning to give, and not simply to give up. It is a way of loving, of moving gradually away from what I want to what God’s world needs. It is liberation from fear, greed and compulsion.” As Christians, we are also called “to accept the world as a sacrament of communion, as a way of sharing with God and our neighbours on a global scale. It is our humble conviction that the divine and the human meet in the slightest detail in the seamless garment of God’s creation, in the last speck of dust of our planet.” (LS, 9)

Liberation from oppression by humanization. The freed person as simply the face faced by the other. The means of liberation as the practice of mercy. The practice of mercy culminating in the hope that our broken communions may be restored. This is Catholicism – with an Eastern twist!

If an Eastern Catholic critique of Francis on not realizing his full potential in geopolitics is pointed, then an Eastern Catholic heart is also melted with the mercy that he shows as a person. It should be of no surprise that the response to quite literally everything in our Byzantine liturgies is Lord, have mercy. It’s always the Year of Mercy for Eastern Christians, and it should be that way for the West too. This is the only prayer – says both Francis and Sam, Yannaras and Bartholomew, Freire and John XXIII – that leads to the liberation of the person.