Today was my first day back on the job teaching. The quarter officially started on Thursday, but I teach on Mondays and Wednesdays.

This quarter, both of my courses are introductory. I am teaching the largest course I’ve ever done, Introduction to Asian American History, which was the biggest class I had ever taught the first time I did it two years ago, but it has just about doubled in size now. The other course is not small either – it is on Chinese American studies, and it is full. I used to think that I preferred small courses, ones where you can actually talk to people and get to know them. I suppose I still have those things: two students have signed up for directed studies courses – one on an Asian American dance community and another on the possibilities of postsecularism in the Pacific – and that’s on top of applying to get my research assistant back on the books, as well as actually have a teaching assistant, a thesis student working on mental health from the perspective of Asian America, and a fantastic colleague who just moved in next door and is already creating with me a kind of convivial community in our hall of faculty offices. Our intellectual community is on fire this year.

Perhaps it is in that context – that I have a community of intellectuals to work with – that I have come to appreciate the large introductory survey course. A wise older colleague who once observed me attempting to teach the big courses – nothing as big as the ones I have now, of course – told me that I had made a rookie mistake as a youthful pedagogue. In attempting to be personal, I treated the large lecture as an unwieldy seminar. Come think with me, she said that my attitude seemed to be in the classroom, and it worked for some, if not many, of the students, so there wasn’t anything wrong with it, per se, except that a seminar is not the same thing as a lecture. They are two different teaching genres.

And so it came to pass that I have been rewriting the lecture courses with this colleague of mine. It has been a learning curve, though much of it has involved the usual struggles on my part. It wasn’t my style, I found myself saying to myself while writing the lectures, which didn’t help with producing them efficiently. The truth was, of course, that it was because it is not my style to be contrived, and I was writing them in an impersonal way, thinking that now that I have these big courses, I’d better get serious and be that detached professor.

I found myself last night still finalizing the lectures when it hit me, perhaps in the wake of having done so many of the Byzantine canons for Matins lately because of this, that, and the other Moleben we offer in Richmond, as well as the fasting-festal season of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, that an introductory lecture course is no more and no less than what we call a canon in our tradition. At Matins, we offer canons, a grid of nine odes that are each based on a canticle in Hebrew Scripture. The odes are divided into threes, and usually the second one of the first set is skipped, as it is penitential and is only sung during those seasons (like when we do the Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete). The first set of odes is on Moses at the Sea of Reeds as well as the Prayer of Hannah in bringing her son the Holy Prophet Samuel to the tabernacle, the second covers the prayers of the Holy Prophets Habakkuk, Isaiah, and Jonah, and the third brings us from Daniel’s friends Hannaniah, Azariah, and Mishael in the fire to the Most Holy Theotokos who fulfills the Hebrew prophecies by bearing God in her womb. Each ode is structured by the canticle, the irmos gives both a melodic and theological theme to the meditations, the tropars that offer Christian commentary on the Hebrew Scriptures along with responses for the festal day, and a katavasia that is a sort of closing verse for the ode.

That, it occurred to me, is what we in academia call a syllabus. For us, the structure of a canon is nothing more than units that are then populated with lectures that have an introduction, body parts to develop the themes, and a conclusion. The role of lecturer is literally that of lector, the reader, guiding the people into reflection on the basic building blocks of a topic. At Matins, that theme involves the continuity of Christian commentary from the Law and the Prophets, finding insight in the most basic of stories and walking the people through them in the reading. For an introductory course, it is breaking down the most fundamental stories, themes, and arguments in the field, arranging them into the grid of a syllabus, and then providing commentary on them by way of introduction. Lecturing is not an impersonal task, especially not at the introductory level. It is deeply personal, meditative and dramatic at the same time, unfolding the most basic elements of a field and a discipline.

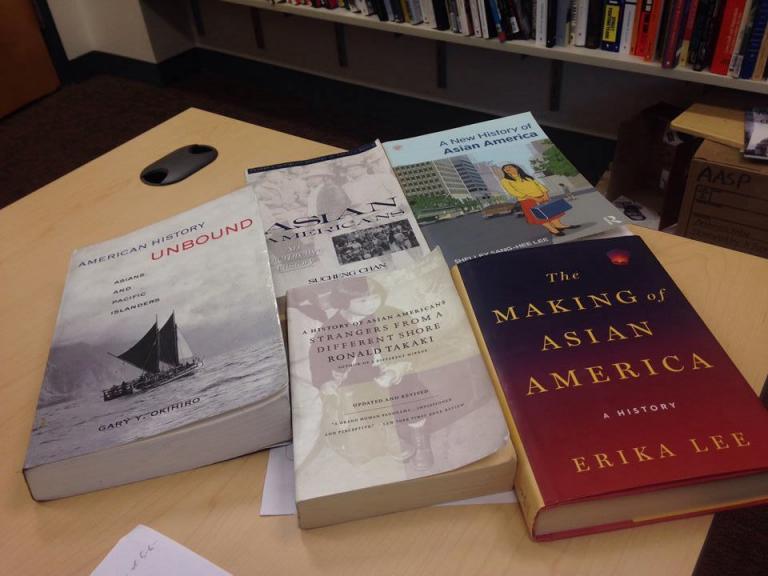

When I saw this analogy, the lectures almost began to write themselves. I went back to the basic texts of both of my courses. In the Asian American history course, we have a series of textbooks that are fundamental not only to undergraduate education, but also to the discipline’s self-understanding of itself: Sucheng Chan’s Asian Americans: An Interpretive History, Ronald Takaki’s Strangers from a Different Shore, Shelley Sang-Hee Lee’s New History of Asian America, Erika Lee’s Making of Asian America, and Gary Okihiro’s American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islanders. Most people will cling to one of these texts as their bible when they try to do Asian American history, but the true master of the craft is able to describe the arguments of each about what is Asian American history, how they are grouped together as schools of thoughts, and how one as an Asian Americanist positions oneself in relation to their debates. Gaining insight into this breadth of texts in the discipline – and there are a few more, to be sure – is, I reflected, a bit like a musician returning to their scales and arpeggios, or a brass musician specifically working on long tones, holding one note for an extended period of time to master timbre, pitch, and breathing.

The large lecture hall that I have for this course has a concert stage. I have never taught in a space like it, but as I came into the room, I saw an opportunity that I had never had. As I assigned the students a warm-up exercise, I took out each of these textbooks from my bag, flipped to the page to the quotes I wanted to capture the basic contours of their argument, and laid them spine outstretched on the floor of the stage like props for a play. When I began to lecture, I simply picked each of them up like a prop. I read them. I put them down. I arranged them on the stage in groups according to themes that were debated among them. I walked between them to show the ways they could be ordered. I could feel the excitement in the room as this scholarly performance was going down, and it struck me in the middle of it that it was as if I was offering a masterclass on the scale, showing how it can be used to practice articulation, nuance phrasing, and be incorporated into composition. I had gone back to the basics, and there was the fire.

My second class was similar, though in a much smaller room. Here was the room to be intimate, but I decided that again, an introductory course should introduce. There, I am returning also to the basics of Chinese American studies, moving in the first half of the quarter to cover basic Chinese American history, its migration patterns, global significance, and legal implications. We will be reading classics in the field and covering the contest among them – Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior, Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club, Louis Chu’s Eat a Bowl of Tea, and Frank Chin’s bombastic Aiiieeeee! series. We will talk about the significance of Mulan in this world, both the Disney and the real Chinese versions. We will go back to the basics.

This, too, was a good exercise for me. In my world, everybody already knows what the immigrant exclusion laws are, why The Joy Luck Club is far from a good representation of Chinese America, and who Mulan is. But going back to the basics rekindled in that very room a passion for the discipline. I will have the chance to walk another class through the debates between Chinese American feminists and Frank Chin. I’ll be able to break down what ‘Chinese culture’ is yet again. I’ll get a chance to talk about the trans-Pacific geography by which Chinese America is really framed.

I am, I confess, all too easily susceptible to getting too fancy with my scholarly craft. Now I see the utility of an introductory survey lecture all on its own – not as a glorified seminar, but a genre unto itself. It is where I come off my high horse and engage the basics as if they were fresh. I play my scales, arpeggios, and long tones. I meditate on the stories of the canon. I develop themes from the sources themselves yet again. I am, in other words, very excited about what this new academic year will bring in terms of my growth in this profession. I am coming back to the basics.