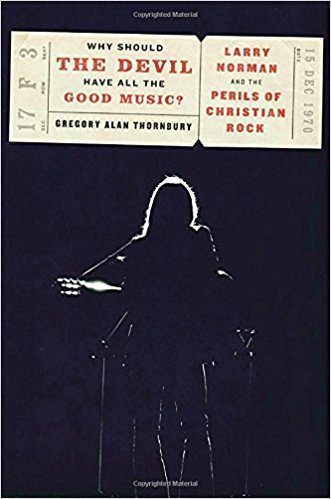

The new biography about rock musician Larry Norman by Greg Thornbury is an important text for understanding this American cultural moment. The book suggests that there were alternatives to the present condition of Protestant Christianity, an argument that fits my experience.

The new biography about rock musician Larry Norman by Greg Thornbury is an important text for understanding this American cultural moment. The book suggests that there were alternatives to the present condition of Protestant Christianity, an argument that fits my experience.

If you are bewildered how we got here, wherever here is, then take and read. There are hints at a better way and hope that much that is good can be recovered. Norman tried to live as a Christian in a field where this was very difficult and sometimes failed. That failure counts. He also did better than he might have done, because he had that standard out there as an aspiration. Those of us who also aspire to do better and fail can take note: Norman listened and chewed over ideas that were contrary to his own all his life. He did not settle on answers hastily, something I have done, but am trying not to do. This hesitation is an internal dialog, with intellectual humility and humanity, and is part of why Norman still has something to teach us.

As I dialog with this book, I am reminded how much more complicated history is than can fit into one book or one take. The Jesus People revival could have gone a different route and avoided the mess of a grifter, televangelist, sub-culture. People made choices and they could have chosen differently, sort of.

1970’s ruling class culture did not want traditional Christian ideas. Though they were (at the time) the views of the majority, they had already been dismissed, generally without argument. Religion that made truth claims was a nuisance. A television show like Adam 12 (produced by man-for-many-media Jack Webb) still affirmed monogamy and chastity before marriage, but the cutting edge of the arts was Woody Allen and (to a lesser extent) Hugh Hefner, not Jack Webb. As a kid, Dad could still turn off the television if God’s name was used in profanity and do so rarely enough that I recall this happening only once. Still, such a decision was not where things were going.

Thornbury makes plain that religion hurt Larry Norman’s career. There might be millions of Christians, and they were even more traditional in the 1960’s and 1970’s, but the gatekeepers were not thrilled with his God-talk. Whenever God-talk or belief had to be noticed, we were treated with newsmagazine covers that discovered “born again” language in a nation that was only fifty years removed from the life of three-time Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, Democrat and populist, who centered his entire successful career on religious language. Jimmy Carter was not new at all, but was treated as if he was.

One reason the grifters and frauds had space to set up a Christin cultural slum was that nobody else really wanted to tell our stories. We still should not (then or now) have gone ahead with ghost written books, cheesy movies, and bad albums, but at the time the options were limited. Stories that fit a white-secular-liberal paradigm were easy to get. Anything else? Not so easy.

Larry had to be very good to sort-of-make-it in a secular industry that manufactured mediocre groups now mostly forgotten. Any religion was too much. Why was praying before a meal so rare that when a show set in the past Little House (or Blue Bloods) does this simple act, one millions of Americans do daily, it is remarkable?

One reason the Christian slum exists is that Christian artists often had to shut up and sing in secular venues. That is not an excuse, though for our building the slum: your telling me I cannot eat at your house does not mean I have to go build a dump and call it a restaurant.

Thornbury grasps that secular injustice, while real, is not the most important fact or cause of failure. Racism destroyed the hopes of the Jesus movement. Traditional Christianity is a global religion and American Christians (who would have agreed with Norman) were black and white, but white racism destroyed any possible alliances. When charismatics looked to the established Pentecostal churches for guidance, they too often were put into a system that had intentionally divided over race. My Dad was present for and supportive of the Memphis Miracle decades later that tried to end this divide, but even then not enough was done.

The sin of racism cut white artists off from the creative source of much of the best and highest Christian art: the African-American community. The white majority in the Jesus movement did not gain the intellectual and theological resources of African-American theology that would have done much to check growing jingoism or prosperity teaching. The Jesus Movement began with a high view of Martin Luther King and prophetic calls against injustice, but this died.

Why?

The leadership of the Jesus Movement segregated. This (of course) is the sin of those with more power, however small, and if things were hard for majority-culture Christian artists, they were doubly hard for Christian African-Americans. Of course, Norman himself through his entire career kept trying to make changes, but he failed.

As the movement gained support from figures like Billy Graham, it should also have looked to the wisdom of a person such as Bishop James Patterson of the Church of God in Christ. The failure to do so and to not promote films, music, and books by, for, and under the leadership of African-American Christians was the moment the movement could not succeed. The gifts, intellectual, cultural, and spiritual, of the largest and most congenial groups of American Christians to the prophetic call in Larry Norman’s music, indeed the very source of that music (as he acknowledged) was marginalized.

In the same manner, the growth of some Christian schools with implicit or even explicit racism tainted that entire movement. Racist curriculum (some still used) from “Christian” publishers infected discourse. A figure such as Francis Schaeffer could easily have been matched (or even surpassed) by thinkers from the traditional Christian African-American community, but this was not done. In the cases of Schaeffer and Norman, this was not malevolent and the idea of integration was always present in their work, but too few white persons went as far as political leaders like Jack Kemp and worked in integrated communities in a co-equal manner.

The inadequacy of Schaeffer’s denominational heritage in terms of race betrayed and limited him. He made amazing strides, but diversity was missing.

Norman blistered the Klan in his music, but the music industry he inspired remained segregated. Again, the legacy of Jim Crow and slavery destroyed what could have been transformative. We could be decades further along with these discussions. Some things were done; tokenism substituted for substance.

Thornbury makes this sad and sinful story evident: a white secular elite that throttled art with too much religion and the failure of the Jesus People to remain integrated on a wide range of social justice causes.* Holiness was always a feature, but so was helping the poor and ending racial injustice. The first emphasis (present in both African-American and white groups) on Holiness endured and attacking the injustice of abortion (forced on the nation in the early 1970’s) was a strength (again often in both groups), but Larry Norman’s emphasis on civil rights and racial justice died in the white parts of the movement.

The road not taken included adding pro-life ideas without diluting, forgetting, or ceasing work on racial justice.

At every point in the history of the 1960’s and 1970’s revival (the Jesus movement, charismatics) there was a live possibility of doing better than was done. Many Christian schools and colleges were not at all “white flight” or founded out of fear. Many like Catholic schools before them, were an attempt to tell stories or live lives that were hard to do in the society. They were often started by people of limited means doing the best they could. There was always a major element that favored social justice causes, nuance, and higher standards. It is easy to find such materials, attempts, and people in the record. Thornbury’s Larry Norman is an important example of this inherent complexity.

It is good to recall this because those of us with roots in the Jesus Movement, Charismatic Movement, or any other traditional Christians looking for a revival of holiness and justice can do so while being true to our best fathers and mothers in the faith. The pathway was there and we can still take it.

Thanks to Greg Thornbury for provoking these thoughts. I hope we can all be ready!

————————

Buy the book.

*The secular versions of the “movement” (hippy culture) also fragmented on racial/racist lines. Both groups (Jesus People and secular counter-culture) hated racism, but both were swallowed up by it.

ready.

I have done three posts on this book. The first is a more general review, the second is a brief reflection on race and racism and the Larry Norman moment, and the third is one on the demons of rock and roll, the rapture, and other weird stuff.