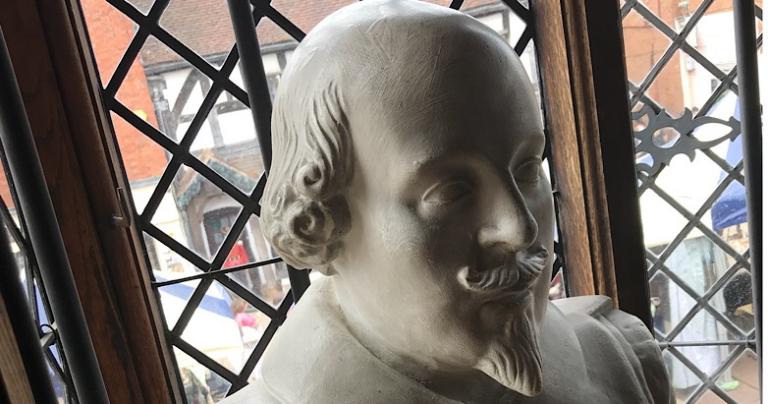

1616 came and Shakespeare and Cervantes died, but Bacon kept writing his way to a New Atlantis. Sadly, people with power ended up taking the New Atlantis more seriously in the short term than they did Shakespeare or Cervantes. Just like the old Atlantis, the new Atlantis would end up drowning in her pride and swamping much that had been good with it. A healthy dose of Shakespearean wit or Cervantes’ deft mockery might have left what was good in Bacon, such as ideas for organized scientific research, and finished off his misunderstandings such as bad philosophy of science.

1616 came and Shakespeare and Cervantes died, but Bacon kept writing his way to a New Atlantis. Sadly, people with power ended up taking the New Atlantis more seriously in the short term than they did Shakespeare or Cervantes. Just like the old Atlantis, the new Atlantis would end up drowning in her pride and swamping much that had been good with it. A healthy dose of Shakespearean wit or Cervantes’ deft mockery might have left what was good in Bacon, such as ideas for organized scientific research, and finished off his misunderstandings such as bad philosophy of science.

Bacon was just one example of people with good or profound ideas that by the middle of the seventeenth century were setting up Western Europe, and the rest of the world influenced by that region, for problems. Descartes got much right, but like all profound thinkers, his errors were magnified in his students.

Sometimes a culture takes a right road, sometimes it passes the right way and ends up a bit lost. Western Europe had a chance at the start of seventeenth century to get a few things right, but by the eighteenth century most had taken a worse way: Enlightenment or reaction. Enlightenment lost the wisdom of the Middle Ages, creating the myth of a dark age, and the main enlightened nation, France, ended the seventeenth century in butchery and dictatorship. Instead of the development of an urbane Spain Cervantes might have prefigured, there was a mere reaction away from the new ideas, including the good ones.

Voices that might have stopped colonialism or at least made it profoundly better were ignored. Moral norms regressed or were not applied to “others” sometimes next-door, mostly overseas. Of course, the sixteenth century had already seen disasterous colonial adventures from Spain and to a lesser degree England and other European powers, but the worst had not yet hardened into attitudes beyond hope of change. By the end of the seventeenth century, ideas about warfare of a Medieval pope such as Innocent IV that could have developed into a better set of ideas about contact with other people had been rejected when not merely forgotten.

Why?

An error of those who came after Shakespeare or Cervantes was to cut themselves off from the ideas of the Middle Ages.

Partly this is because the lively intellectual culture of the Middle Ages that birthed the Scientific Revolution was ossified by the sixteenth century. The university curriculum had become overly rigid and other sources for ideas were springing up. Shakespeare, the working playwright, is an example of the new popular theater producing great work. Science was too often ignored in favor of rote “classical” learning. Yet Cambridge could still produce Edmund Spenser and the classics and theologians of the Middle Ages had the resources to change. University training in medicine was changing, if too slowly.

The Enlightment thinkers forgot Roger Bacon for Francis Bacon and this had consequences. The Middle Ages had one thousand years of intellectual resources that might have kept scientists from confusing Francis Bacon’s ideas about science (Baconism) with science.

Science was quickly solving many problems and falsifying old ideas about the world. This led to “scientism” and a dangerous “Utopianism.”

Christian colonialists in the sixteenth century proved that Christians who wanted to make money or get power can easily ignore the precepts of their own religion. Still Christianity, especially the Christianity of an international man such as Thomas Aquinas, was always going to be an uncomfortable fit with colonialism. There were always intellectual resources in a religion that began with the precept “love your neighbor as yourself” to challenge bad actions.

The only way around this was to pretend (monstrously) that the “they” were somehow not human or sub-human. If science, born out of the Middle Ages, had kept in contact with the best of Christian ethical thought (instead of rejecting the entire tradition as part of a Dark Age) proper science would have shown the belief that First Nations in the New World were “less than” was nonsense.

If like Shakespeare, seventeenth and eighteenth century thinkers had embraced the truth that science is not the only means to knowledge, Europeans might have been able to see the wisdom and cultural riches of First Nations. Instead, having “science” became the mark of real civilization and the errors of the early colonialists were doubled without even the hope of intellectual resource to challenge those errors.

If a missionary zeal to save souls could be corrupted, despite beginning (ostensibly) in love, scientism which began in a pride so great that practioners called themselves enlightened and their own intellectual parents dark was bound to lead to worse abuse. We needn’t guess: it did and does.

For the Baconians or Enlightenment types, “nature” was to be tamed and the attitudes of a play such as As You Like It toward the country (as opposed to the corrupt court) are gone. Scientific advance was and is doing great good, but the implementation of that good in areas such as medical care took a mechanistic turn that ignored humane wisdom from everyone, but especially from the barbarians.

Instead of creation care, loving the world God made, the Enlightenment made matter and even life merely chemistry. We reduced nature to parts and this eventually would apply to even humankind. This reduction gave unwarranted confidence that Enlightened Europeans could take the parts apart and make the world better.

Yet we must not simply demonize the Enlightenment or valorize the Middle Ages.

The bad ideas in the Enlightment were missed opportunities, but the good the Enlightenment did is also real. The emphasis on science has done great good. The refusal to just repeat old ideas as true merely because they are old was good. A genial skepticism about authority is always wise. Enlightment thinkers pretended they were making the world anew, but really built on ideas from the Middle Ages. The research university has problems, but has been (mostly) a great boon to human happiness.

The bad ideas of the Middle Ages they doubled down on (that led to early sixteenth century colonialism) were there to adopt. The inability of Christian thinkers to adapt scholastic ideas quickly enough was lazy and part of the problem. Merely rejecting Enlightenment ideas with obscurantism or the use of power was bad.

So we must not repeat the Enlightenment error of demonizing what came before us. Our world is better for the Enlightenment in many ways and we would not want to lose them, yet surely we are at the point where the moves of an “enlightened” ruler like Catherine the Great look not so great. An ocean filling up with plastic makes the gentle love of nature in the Britain of Shakespeare look more attractive than crude Baconism.

Let’s take a different road than rejecting the Enlightenment, let’s try to dig deep in many cultures and see if we can preserve the good without the bad. Shakespeare and Cervantes are not bad writers to start us off if like most Texans we speak either English or Spanish as our mother tongue.

——————————-

This is a short devotional version of a longer talk given at The College at The Saint Constantine School.