When the state is divinized, tyranny follows.

When the state is divinized, tyranny follows.

All rulers, even the best, are tempted to conflate their own legitimate power with God’s rule. Christians have tried this trick and the results stand as a shame to us and a warning to others. Atheist states have done something similar, though the Ideology that comes from Science (not to be questioned!) replaces God. Democracy becomes mob rule just at the moment the voice of the people is confused with the voice of God.

There must always remain a healthy distinction between God’s laws and man’s customs.

Why?

Plato Helps Us: Moral Laws, Laws and Customs

Plato begins his last dialog, unfinished, rough but brilliant, with a question from an Athenian stranger to two gentlemen (one a native of Crete and the other a citizen of Sparta):

Is it a god or some human being, strangers, who is given the credit for laying down your laws?

Kleinias replies:

A god, stranger, a god- to say what is at any rate the most just thing.*

Notice that the three men, who will discuss the ideal state so long it takes hundreds of pages to record their conversation, begin by calling each other “strangers.” They know each other, but the distance between the two gentlemen (Kleinias and Megillus) and the sage from Athens is heightened by the text never using the name of the Athenian. He is always “the Athenian stranger,” perhaps Socrates, perhaps not.

He is not a Cretan or a Spartan and is an Athenian and only an Athenian.

This is our clue to the idea of “laws” and “law making” central to the text. “Laws” are not just the legal pronouncements of the City, but also the customs that govern our lives when the government cannot not. Custom is the law when no police are present and there is no chance of getting caught.

The laws and customs of any community are unique to that community so an Athenian can never, quite, be a Cretan or a person from Crete an Athenian.* They are strangers, separated by different customs and laws. Obviously this does not mean a total separation or that one is superior to the other. They are joined in being men of Greek culture (more general than the particular city), a delight in discourse, and a love of wisdom.

They are educated men and that unites them, but they are still (on one level) strangers to each other: Athenian and two Cretans.

There is a moral foundation that unites them as well, but that too while common to any city is not enough to be a City.

Moral Foundations Not the Same as the Laws Being Divine

The good God has created a world either based on separate, but dependent laws or on permanent ideas in His mind. Plato can be read either way. Most Christians prefer to think of the moral law as an idea in the mind of God, forever unchanging, but some have them those laws are not God or part of God, but eternally dependent on God for existence.

They exist because of God, but as God is eternal, so they are eternal.**

These laws matter, because they provide an underpinning for the moral universe. One need not even believe in God (though one should) to have access to them. Moral laws are not likely to exist and undergird the actions of the material world without the Mind of the Creator, but they might. In any case, a person can be wrong about one thing (the existence of God) and still discover other things (numbers, moral truths) that exist in the cosmos.

This is good news. So why can’t the laws of the City just come from the Mind of God (or the contingent moral facts)?

The moral order is not enough to govern a particular city at a particular time. The laws must be expressed in particular ways and this expression comes from the agents, people, God created with free wills. That should have led to a diversity of customs, all good, none bad, but that were different. God’s cosmos could have had a particular City with a particular celebration of athletic prowess and another where poetry was emphasized. One city might have provided more liberty, another more order. Our adherence to the moral order shows us children of God, our customs as men.

None would have cultivated mobs or tyrants.

The world is not as it should be, so these particular expressions or customs, good in themselves, become bad at times. People are punished for peccadillos. One particular City thinks herself and her way of living as better than all others and becomes jingoistic.

We should be strangers who delight in our strangeness to each other . . . Looking on in wonder as we travel a diverse world. Instead, we homogenize and destroy. This danger is very present when we confuse the moral order, the laws of God, with the customs of the City.

The rulers of the City must support the moral order, but they did not create it. The rulers of the City must never confuse their customs or even their particular applications of the moral order with the Will of God.

A Healthy Church and State Distinction

The best image of this relationship is in the two-headed eagle of the Christian Roman East. The Western eagle has but one head and so church (the keepers of the moral law) and the state (keepers of custom) vie to be that ultimate guide to the one body.

The east had a powerful patriarch and a powerful emperor. Both had limits, both could rebuke the other. So long as the tension existed in the Eastern Roman commonwealth of nations, then health was possible. This is part of the reason the East could maintain a “secular” (not theological) university and theological study at all times in her history.

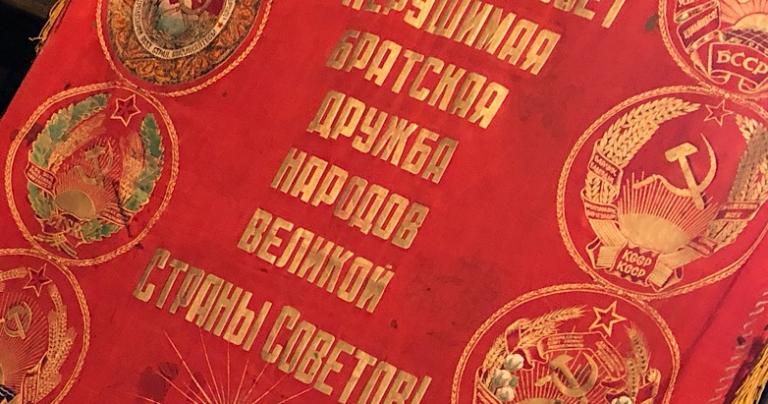

Conquest by Islam, which struggles to separate the moral law from the civil custom, ended hope in most of the Commonwealth. Russia faltered when Peter the Great, imitating the West, destroyed the Moscow patriarchate. The Church became too subordinate to the state and could not act as conscience as easily. Nicholas II restored the balance by restoring the patriarchate, but too late.

The new atheists demanded a single ruler, the Divine State.

The American founding, brilliantly turning to the Roman republic and not empire, separated church and state without divorcing influence between the two institutions. The church informed the culture with the moral law. Since this law was compatible with the views of deists and Jewish people, this meant the Christian super-majority in a nation with limited government left most people alone. Out of many expressions of the moral law could come one people.

This brilliant compromise is now being threatened by a statism that rejects the universal moral law and is based on a shifting mix of libertine desires and scientism.

This will inevitably lead to a confusion between what can be tolerated (radical dissenters like the Amish or the village atheist in the old order) and what cannot (any dissent from elite opinion in the new regime). We risk unifying the priesthood (now the University professor) and the rulers.

Theocracy for the religious would be as bad, so no response.

And so it goes. The Eagle must have two heads.

—————————————-

Plato, The Laws (translation by Thomas Pangle).

*The Spartan? I would suggest he has an indentity, but one that is more pliable.

**The same discussion takes place regarding the existence of numbers: in God’s mind or logically dependent.