To avoid the supernatural, a person must never see nature as a whole, but always, quickly, break her into parts. We speak of what makes up a star and not the spangled sky. Wonder makes us wander from any narrow explanation that explains everything easily: thoughtless naturalism.

To avoid the supernatural, a person must never see nature as a whole, but always, quickly, break her into parts. We speak of what makes up a star and not the spangled sky. Wonder makes us wander from any narrow explanation that explains everything easily: thoughtless naturalism.

What is behind it all? Ancient philosophers moved to atheism to avoid fear, the worry about what may be underneath it all. If there was no life after death, no active gods or a God, then one need not worry or wonder about what this might mean. All, pan in Greek, might be wonderful, but given our experience might very well be horrible. So the Epicureans banished all evidence of marvels, including the cosmic marvel to banish fear.

It does not work unless numbing the mind, making insensitive the soul, can be said to work. Perfect fear casts out many kinds of love. Plato and Christianity refused fear and looked to love (Symposium and Gospel of John). The New Testament in particular saw the Heavens proclaiming the glory of God, but did not deny death and decay.

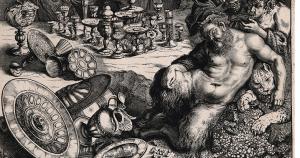

The ancients recognized that something had gone wrong in nature. All was not as it should be. Ovid and others imagined this rebellion against reason in satyrs and nature gods who were (almost) wholly fearful for mortal men. They might revel like men, but were more than men and so could never be safe companions. Their revels were too often a prelude to rape and rapine.

Was this what was basic about the world? Did death end with us in the power of such gods as Homer describes and Ovid ornaments? Was nature essentially frightening? Was the daemonic basic to the world? Or was it just a broken feature? Plato and Christianity said there was something deeper than Pan and the nature gods, the Creator God.

He was not one more nature god: God was nothing like them. He was Pan . . . Not as nature, but as the All Powerful, All Good, All Beneficent, All Wise. The nature gods are tamed in the light of the God who was Pan. Plato has Socrates put this plainly at the end of Phaedrus:

SOCRATES: Beloved Pan, and all ye other gods who haunt this place, give me beauty in the inward soul; and may the outward and inward man be at one. May I reckon the wise to be the wealthy, and may I have such a quantity of gold as a temperate man and he only can bear and carry.—Anything more? The prayer, I think, is enough for me.

PHAEDRUS: Ask the same for me, for friends should have all things in common.

SOCRATES: Let us go.

Here Pan, associated with All, is asked for beauty, harmony, and wisdom. Nothing could be less like the Pan of the myths. God undergirds the world, so the gods of nature, the demons of antiquity, are not what is basic. One could hope to do science, because the nature gods, at best whimsical and at the worst tyrannical, driven by irrational desire, were not the Creator. The Creator spoke mathematics. He was good, beautiful, and wise: All Good, All Beautiful, and All Wise,

Christian culture would bury her dead with a realization of decay. The tombs showed the skeleton, the decay, but in a cathedral that pointed to Paradise and the deeper science of a joyful world.

Christian culture would bury her dead with a realization of decay. The tombs showed the skeleton, the decay, but in a cathedral that pointed to Paradise and the deeper science of a joyful world.

The remnants of Christian culture (or neoplatonism in educated England) allowed a cheerful view of nature to survive even when Christianity faded to the background. In Wind and the Willows (Kenneth Grahame) we get the Christianized Pan. In this wonderful book, Mole and Rat are looking for a lost animal. They find the child with god of animals, Pan:

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humourously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter.

All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered. ‘Rat!’ he found breath to whisper, shaking. ‘Are you afraid?’ ‘Afraid?’ murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. ‘Afraid! Of HIM? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!’ Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship. Sudden and magnificent, the sun’s broad golden disc showed itself over the horizon facing them; and the first rays, shooting across the level water-meadows, took the animals full in the eyes and dazzled them. When they were able to look once more, the Vision had vanished, and the air was full of the carol of birds that hailed the dawn.*

This is a wonderful book, but there is something false in this image and in the book. Grahame writes beautifully, the equal to anyone in his era, but he has not grounding. Pan is lovely, but just as the animals ignore the fact that many of their neighbors make their living eating them, so Grahame ignores Pan. Nature, red in tooth and claw, Darwin without a Deity, is never going to be kind for very long.

If Pan is a god and not God, then he is bound to be terrible. A lesser writer, but a more consistent thinker, Arthur Machen** saw this plainly in his horror literature from the same period. Machen saw that naturalism and atheism were a kind of irrationality, denying human experience. Extreme skepticism was simply the reaction of the fearful to the bad news that nature by herself did not and could not love us. In his fiction, Machen often has his heroes say things like this: ‘My dear Phillipps, you are a living example of the truth of the axiom that extreme scepticism is mere credulity.”

Just so.

Wind in the Willows is more beautiful than any book that Machen wrote. Machen lacked Grahame’s literary ability, but Machen was logical and so his Pan was the Pan of the pre-Platonist, pre-Christian world:

You remember that still summer night so many years ago, when I talked to you of the world beyond the shadows, and of the god Pan. You remember Mary. She was the mother of Helen Vaughan, who was born nine months after that night. Mary never recovered her reason. She lay, as you saw her, all the while upon her bed, and a few days after the child was born, she died. I fancy that just at the last she knew me; I was standing by the bed, and the old look came into her eyes for a second, and then she shuddered and groaned and died. It was an ill work I did that night, when you were present; I broke open the door of the house of life, without knowing or caring what might pass forth or enter in. I recollect your telling me at the time, sharply enough, and rightly enough too, in one sense, that I had ruined the reason of a human being by a foolish experiment, based on an absurd theory. You did well to blame me, but my theory was not all absurdity. What I said Mary would see, she saw, but I forgot that no human eyes could look on such a vision with impunity. And I forgot, as I have just said, that when the house of life is thus thrown open, there may enter in that for which we have no name, and human flesh may become the veil of a horror one dare not express.***

The rise of the Nones, if it continues, will not lead to more atheists. The atheist boom has passed. It will lead to paganism, but not the cheerful wholly invented sort of Kenneth Grahame. Instead, it will be the dark, realities of Machen and HP Lovecraft: a future more Cthulhu than Christopher Hitchens. Pan can be the God of the philosophers and of Christian revelation: philosophy showing us He is, revelation that He loves us. If not, Pan will not long be benevolent, because nature with Nature’s God (Locke and Jefferson!) becomes the satyr, the demon of desire. God devolves to a god: Being to a mere being.

Against this CS Lewis stands as a hopeful corrective, the party without the crimes, nature without despair, Pan and the satyrs, made safer by the very presence of the Pan, the dangerous but All Good Asian:

Then Bacchus and Silenus and the Maenads began a dance, far wilder than the dance of the trees; not merely a dance for fun and beauty (though it was that too) but a magic dance of plenty, and where their hands touched, and where their feet fell, the feast came into existence—sides of roasted meat that filled the grove with delicious smell, and wheaten cakes and oaten cakes, honey and many-colored sugars and cream as thick as porridge and as smooth as still water, peaches, nectarines, pomegranates, pears, grapes, strawberries, raspberries—pyramids and cataracts of fruit. Then, in great wooden cups and bowls and mazers, wreathed with ivy, came the wines; dark, thick ones like syrups of mulberry juice, and clear red ones like red jellies liquefied, and yellow wines and green wines and yellow-green and greenish-yellow.****

So on the day when many Christians recall that death of the God-man, we recall that God is Pan: all Good and so nature is knowable and life bearable.

———————————————

*Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame.

**Machen is Lovecraft with writing skills, a lesser Doyle.

***The Great God Pan, page 53 Arthur Machen, (Oxford World’s Classics)

****Prince Caspian, page 210 CS Lewis.