Friendship is powerful, perhaps the most powerful, of all the loves.

Friendship is powerful, perhaps the most powerful, of all the loves.

David loved Jonathon. Naomi loved Ruth. Achilles loved Patroclus. Pause for a moment and assume they were indeed “just friends” and consider this: the love of friends is mighty.

The friend is someone you love only for himself and with whom you share a common cause. In Homer’s Iliad, Achilles loves his friend Patroclus disinterestedly. Achilles sleeps with his captive Brieseis, but she is a prize, something less than human to Achilles. When the King of Kings seizes her, Achilles regrets the loss, but only because this shames him. He never seems aware that having killed those she loves and capturing her she does not consent to any relationship.

One man, Patroclus, is kind to Briseis and when he dies, she mourns him. Patroclus amongst the Greeks is like Hector in Troy: the one decent man. Being a friend to this gentle man makes Achilles better, just as being Hector’s brother provides the few moments of manliness from the cad Paris.

If we were to sexualize the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, as later Greeks did, then much of the merit of Patroclus’ kindness is lost. The Iliad portrays him as sleeping with women, but despite his interest in women, he is kind to a stunning woman over whom he has all power. Patroclus as a friend to Achilles is a rebuke to Achilles and he knows it. Patroclus makes him a better man, so when his friend dies, Achilles has lost not just a chum, but his moral compass.

Achilles is the nuclear bomb of the Mycenaean world: nobody can beat him except accidentally. If he shows up, his team wins. He is consumed by a divine wrath, the heritage of his divine mother. Patroclus calls up his father, his human side, the son of Peleus that can give an old man (Priam) the body of his son (Hector) even though the son (Hector) has killed his best friend (Patroclus). Even in death Patroclus makes Achilles better than he was.

Achilles’ goddess mother, who enables all his vices, shows up as Achilles mourns the death of his friend:

Dawn veiled in saffron rose from the streams of Ocean, to carry light to the immortals and to mortal men, and Thetis arrived at the ships carrying the gifts from Hephaestus. She found her beloved son lying with his arms around Patroclus, keening, and his many companions about him dissolved in tears; and she stood among them, the shining among goddesses, and clasped his hand, and spoke to him and said his name: “My child, grieved though we be, we must leave this one lie, since by the will of the gods, he has been broken once for all; you now take the splendid armor from Hephaestus, exceeding in beauty, such as a mortal man has never worn upon his shoulders.”*

She comes and gives him the armor that will allow him to kill Hector, getting revenge for Patroclus’ death. She is giving him what he wants, but what he wants, the death of Hector, will hasten his own death. Mother is enabling the destruction of her son and, after all, as she is immortal: why not? She has one child: Achilles. The human she is stuck with as progeny can be a glorious hero or live a long time, but die he must. Why shouldn’t she root for glory and the grave?

She is not going to die: ever.

Patroclus, kind Patroclus, would never do this. He goes out in the armor of Achilles to save the Greeks and save the honor of his friend. He fails mightily in battle, but is a man. The death of Patroclus makes Achilles a better man.

Put simply, Homer is giving practical advice to his reader: find a friend that is gentle and kind. Find a friend like Patroclus.

——————————-

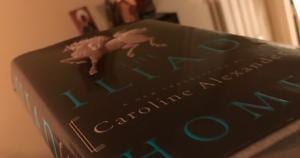

Iliad, Homer. (Translated by Caroline Alexander) Book XIX, line 1 ff .