Listen to the old men and women, even if they tend to natter.

Listen to the old men and women, even if they tend to natter.

So the wise poet Homer teaches us, even if an old person makes it hard to listen. The most prominent old man of Iliad is Nestor and if you ever read the poem aloud, and you should, then you will know the dread when you realize aged Nestor is about to speak. When Nestor speaks you can be nearly sure of two things:

- He will tell you men are not nearly as great as the men were when he was young. In fact, the enemies, monsters, foes of gods and men, are not so fearsome. Deeds were done in his day!

- He wishes he were young again so he could show the Trojans a thing or two.

Nestor pads every speech with anecdotes from his day when men were men and meanders to his point.* Next to the list of ships, his passages most tempt the mind to wander. Nestor is full of wander. A good writer would be done, but Homer is a great poet and so he does more. Embedded in Nestor’s method is mercy: he talks just long enough, distracts just enough, to prevent great folly in the Greek camp. The old man is artful. He cannot use force, but his words sooth: he is no fool.

There is an interesting possibility: perhaps Nestor is not wrong and men were greater when he was young. The monsters in the myths he made were greater than the embattled Trojans and their allies that the present generation has spent a decade failing to defeat. If old men are tempted to overrate the glories of their youth, this might cause us to forget that sometimes (often?) an era does decline from past glories, not in every way, but some ways. We are not somehow, someway, getting better in every way.

The older voice recalls some lost goods that should not be forgotten.

Old men may recollect better times. Nestor is not the only old man in Iliad. When the Greeks send an embassy to Achilles to try to get him to return to the fight, they send his old mentor Phoinix. Achilles refuses to listen and:

At length Phoinix the aged horseman addressed him, bursting forth in tears; for he feared greatly for the ships of the Achaeans:

“If now you ponder going home, shining Achilles, and you do not intend in any way at all to defend the swift ships from obliterating fire, because rage has assailed your heart, how, then, apart from you, dear child, could I be left here on my own? With you the aged horseman Peleus dispatched me on that day, when he sent you from Phthia to Agamemnon, a child, knowing nothing of indiscriminate war, 440 nor of speaking in assembly, where men develop distinction; for that reason he sent me out to teach you all these things, to be both a speaker of words and a performer of deeds.”**

Homer shows us another strength of the old: they have no desire to live past their children, physical or spiritual. If Achilles leaves, then Phoinix will be left alone. The old man came to be with Achilles, to train him, to see him flourish as a man and warrior. The mentor succeeded and Achilles is not the greatest of the Greek fighters, but Achilles will not fight. Achilles has learned to speak well, to lead, but he is sulking in his tent. Phoinix knows his day of glory has gone and does not envy Achilles, but weeps to see the young man squander moments of greatness. He knows, as only an old hero does, that the day of glory cannot be recalled once it is gone. The scene is more tragic, because all know the fate of Achilles: he will die young. Every day he wastes is one less to make his mark.

The older voice can inspire greatness in the younger person without envy.

The other quality that Homer shows in the old is fearlessness. The old have seen it all, know the end for them is near, and so have the liberty to act fearlessly for justice. Troy is ruled by an old man, Priam, who starts the war with many riches, a great city, and numerous sons and finishes the war with nothing, ruins, and nobody. When this old man speaks as the poem draws to a close, he pleads for the body of his son, Hector.

He is fearless and Achilles is moved. Old men are hard to hear, but may we like Achilles, even in sorrow and rage, hear their wisdom and recollect mercy.

The older voice is fearless for justice and mercy with little to lose.

The older voices in my life have been and are wise and, unlike those in Homer, filled with a “progressive vision.” As I grow old, I hope to be as Homer suggests: a voice that remembers, inspires, and is fearless.

God help us all.

—————————————

*As I enter the youth of old age, I plead for mercy and more self-awareness of Nestor-like tendencies.

**This is from Book IX of the Iliad.

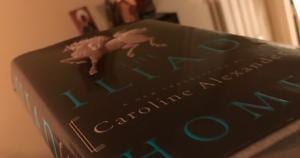

The translation by Caroline Alexander is far and away the best available in English.