It is clear then that the essential object of love, or the Beloved, is “whatever.”

So said Professor Alfred Geier,* but if we pause and understand, then a life changing truth will result.

So said Professor Alfred Geier,* but if we pause and understand, then a life changing truth will result.

Over a lifetime Plato reflected on the life of Socrates and discovered a few essential truths about humankind. These ideas have been disputed and those disputes are the footnotes to philosophy.**

In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates and the tragic poet Agathon are discussing “love.” What is love? Both realize that there exists a longing, a love, that cannot be satisfied by a human person, a City, or even ideas. We love something. Agathon and Socrates agree on this and if love comes, then (in all probability) love is of something. Something causes the desire that cannot be satisfied, is not sated, by any finite being.

We have eternity in our hearts. Agathon is sure his love is of something, a something Geier translates as “whatever.” The Beloved Uknown is there, has done this, and yet that is not the Beloved. The sign, the very icon of the Beloved, is not the Beloved. He is there until we look there and then the Beloved is gone.

What is that something that causes love? Who knows? We know we love, but for Plato this Beloved (so divine!) is known to exist, but unknown. Professor Geier concludes that this mystery (my term) allows all learning in humankind. We see a tentative truth, but always are (not quite) sure. We wonder and the wonder, the knowledge that not only may we be wrong (obviously), but that our picture of the Beloved is so limited that the picture might as well be false keeps us learning.

The Beloved is eternal, unchanging. We are neither of those things. We can know, but the Beloved cannot be exhausted. There is always more and this uncertainty, this “all may change” is the basis for learning. In another dialogue, Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates faces a Phaedrus (his very name is “bright one”) that is in love, but badly. Socrates and Phaedrus talk, Socrates listens, and slowly both are changed. Socrates starts enamored with the handsome Phaedrus while he is in love with a speech he has heard from another teacher.

Socrates starts to give another speech and in the middle stops. He has stopped focusing on Phaedrus (Geier, 89ff) and turned toward the Beloved Unknown. He begins to speak poetically and finally stops:

Socrates: And now, dear Phaedrus, I shall pause for an instant to ask whether you do not think me, as I appear to myself, inspired?

PHAEDRUS: Yes, Socrates, you seem to have a very unusual flow of words.

SOCRATES: Listen to me, then, in silence; for surely the place is holy; so that you must not wonder, if, as I proceed, I appear to be in a divine fury, for already I am getting into dithyrambics.**

At the end of Phaedrus, Geier points out that the last speaker in the dialogue is actually unknown (though what he said is known!). Translators (usually) choose to give Socrates the literal last word, but the text is ambiguous. There is only one word at the end which means, roughly: we go.*** Phaedrus and Socrates go, together. They know where they are going, where they have been, but they do not know, cannot know, the End. There is no end. . . Just one question leading to another to another world without end.

Amen.

For a Christian, this attitude is vital: we live by faith, not sight. This is not an appeal to non-reason, but to the incomplete knowledge that must always exist regarding the Known Unknown: God. One truth at the very center of Orthodoxy is that we cannot fully describe God. We know best what God is not: limited, powerless, foolish. The Orthodox would not dare limit God. He is not a liar, God is not a sinner, but God is known and unknown, beloved yet never exhausted.

A vital, theological rich, devotionally profound book, Father’s Love Journey, by Professor Fount Shults makes the point that the God of Saint John’s Gospel is always forcing us out of our bubble, theological and philosophic. God the Father comes to be known in the person of Jesus Christ, but as God can never be fully known. Saint John points to Christ, he is not the Christ. John the Baptist is a signpost of the Messiah: the Baptist is not the Messiah.

Even our words about God the Father, truly seen in Jesus are so limited as to almost (but not quite), be false. They are the best words we have: the liberal Christian sure they are too limited, the doctrinaire positive they are the end of all wondering. The Christian begins with what is seen, revealed, and then wonders about more and more. Nothing contradicting, all tentative, all in the great “whatever” of God. The faithful creeds launching us further into a relationship with a God who is known, but can never fully be known.

Let’s worship the God known to be “whatever.” God is that God: not finite, not imperfect, not changing. God is love, but love is that whatever that we love. This mystery, to us not to reality, is a constant joy. We can see love without end for all time and into eternity.

And doing so, wonder of wonders, holding Orthodoxy by faith, knowing our fallibility, and the more and even more that is always there in the Beloved Unknown.

—————————————

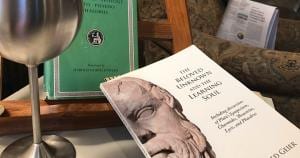

*Geier, Alfred. The Beloved Unknown and the Learning Soul (Tiger Bark Press, 2016)

**Plato, Phaedrus. 238 C. (Lowell translation.)

** To paraphrase sort-of-Whitehead.

***Plato, Phaedrus, 279 C.