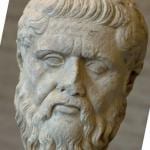

Plato gave the ancient world the form of dialectic education in his writings, especially his masterwork Republic. Plato presented education that began in questioning the received wisdom, moved to constructing a hypothesis about the problem, and ended in a great Myth, the most likely story to explain all of reality. This worldview generates new questions, having become the new received wisdom, and so is refined in the same process. Eventually Plato hoped we would have a vision of the Good and so gain certainty. This seems very abstract, but has been applied at schools for millennia, a pedagogy refined over centuries (by the same process!), and now in use in nursery through college at The Saint Constantine School.

Plato gave the ancient world the form of dialectic education in his writings, especially his masterwork Republic. Plato presented education that began in questioning the received wisdom, moved to constructing a hypothesis about the problem, and ended in a great Myth, the most likely story to explain all of reality. This worldview generates new questions, having become the new received wisdom, and so is refined in the same process. Eventually Plato hoped we would have a vision of the Good and so gain certainty. This seems very abstract, but has been applied at schools for millennia, a pedagogy refined over centuries (by the same process!), and now in use in nursery through college at The Saint Constantine School.

Kindergartener and college student: master received wisdom, dialog in wonder, hypothesize, tell likely stories. Once we seem to be done, having settled all, we begin again. This process may seem to “go in circles,” as some critics suggest and so it does! The circles, however, corkscrew up. The lover of wisdom ascends to better and more complete answers. So in younger grades the image of the atom as a nucleus/sun with electron/planets, gives way to a better image in junior high school, and then to a simple version of quantum theory in high school physics. By college the student might be introduced to something closer to the best contemporary theory when he has the mathematics needed. I am told by my friends in real physics that this process has not yet ended!

A Christian can see this same growth in theology. We slowly gained a better and more consummate understanding of the holy Trinity. After centuries this was refined into a creed, but the questions then shifted to higher and better things! Our wondering never ends, thank God.

Yet this ideal comes with dangers for a Christian. We might forget Jerusalem in a love for Athens. This danger caused Tertullian to thunder that Athens had nothing to do with Jerusalem. Sadly, this only caused Tertullian to miss how much his thinking was dependent on Athens and he ended up in a funny, heretical place.

There is a need for a pastor to keep us from monomania, not Athens or Jerusalem, but Athens as a suburb of Jerusalem!

The pastoral practicality came most clearly from the genius of Saint Basil. Adopting any ideas from the Greeks and Romans who had been persecutors must have been difficult, but the Saint overcame prejudice and did so. He also was not swallowed up by Greek thought as was a less balanced thinker like Origen. He did not cast out Greek thought like Tertullian. Obviously there is a tension in reading the pagan Homer with his polytheism and the truth.

Giving practical advice to young men on the right use of Greek literature, Saint Basil did not deny the tension. He embraced all truth. He put Christian education on this balanced course when he said:

To be sure, we shall become more intimately acquainted with these precepts in the sacred writings, but it is incumbent upon us, for the present, to trace, as it were, the silhouette of virtue in the pagan authors. For those who carefully gather the useful from each book are wont, like mighty rivers, to gain accessions on every hand.

Sacred writings are studied in school and the truths lived in the liturgy. We shall become “more intimately acquainted.” Still Saint Basil saw the quest for virtue in the pagan authors as very valuable. He knew through his own studies, however, how overwhelming teachers in higher education can be. The good Basil did not suggest dropping out of school! Instead, he said:

Now this is my counsel, that you should not unqualifiedly give over your minds to these men, as a ship is surrendered to the rudder, to follow whither they list, but that, while receiving whatever of value they have to offer, you yet recognize what it is wise to ignore.

Basil also returned to the teleology of classical Christian education: we are preparing saints for paradise. Eternity is so much greater than mortal life that all must be measured in that scale, yet with that goal in mind Saint Basil still found value in the pagan classics.

This is a miracle of insight. Homer could teach virtue. Indeed for many of us, Homer is a necessary introduction to the dialectic. We can learn to inquire on a rougher text and so avoid any hint of impiety.

The holy things are for the holy and (especially) younger students are not yet fully ready for the deep things of God. (Many of us older folk are also in this condition!) We read, question, debate, and try to understand lesser books such as the Iliad. There our mistakes count for less!

We find virtue in these writings, but even the errors can teach us:

If, then, there is any affinity between the two literatures, a knowledge of them should be useful to us in our search for truth; if not, the comparison, by emphasizing the contrast, will be of no small service in strengthening our regard for the better one.

Saint Basil also distinguishes between reading and praising. We read to understand and then choose to praise the good and condemn the bad we find in such writings. The fundamentalist cannot read, he is weak. The syncretist reads and is uncritical. Saint Basil urges us to read and be discerning.

This process can shine a further pastoral light on us as we can read without doing. We do what is good, weeding out any call to vice in a pagan (or Christian!) text. We should not just read about virtue, but go practice good works.

Another great vice of some classical Christian schools is that they hear, talk, hear some more, talk a lot more and do nothing. We should emulate the great Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King and strive to stand with justice and bring forth the beloved community: hearers and doers.

————————————————

Saint Basil. To the Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature.

For more on Plato and education: See chapter six in my When Athens Met Jerusalem.

On King and doing: See his sermon Guidelines for a Constructive Church. I summarize this sermon with links to the full message here.