What if we turned from academic theology to “common theology?” Would we find intriguing ideas in the great conversation of a diversity of theology minds? Dr. Eric Holloway thinks so and he wishes us to think with him.

What if we turned from academic theology to “common theology?” Would we find intriguing ideas in the great conversation of a diversity of theology minds? Dr. Eric Holloway thinks so and he wishes us to think with him.

Dr. Eric Holloway has a great texts degree, a MSc in Computer Science at the Air Force Institute of Technology and a PhD in Computer Engineering at Baylor University.

Dr. Holloway:

What if theology were a knowledge based discipline like philosophy,

science and mathematics? Today, if one cracks a theology textbook,

there is much discussion about religious scriptures, systematic

analysis of the scriptures, and delineation of doctrine. However, it

is all very distant from our common theology.What do I mean by common theology? To understand, we have to first

look at the sibling of common theology: common philosophy. The origin

of philosophy in Greek culture was very tied to everyday life.

Socrates talked with common folk in the market place. Plate wrote up

Socrates’ ideas in engaging dialogues. In most of the dialogues, the

participants dealt with questions that applied to everyone’s life,

such as whether it was better to be good or powerful, the ultimate

purpose in life, why celebrities don’t know what they’re talking

about, and so on. Very nitty gritty and relevant. In this down to

earth setting, Socrates was able to investigate profound questions

that reached beyond our world. This is what I mean by common

philosophy.What if there were likewise a common theology? Common theology is a

way of talking about whether there is an overarching intelligence

guiding the universe, and what its nature might be, in words people

like ourselves can understand. In fact, this notion of a common

theology started Socrates on his philosophical investigations.In Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, Socrates states he was unsatisfied with

the intellectuals of his day and their explanations. When asked why a

man walks, the intellectuals would say because his leg muscles pulled

his bones. This was not the sort of explanation Socrates was looking

for. Socrates wanted to understand the purpose behind the man

walking. So, when asked why a man walks, Socrates would say because

the man wished to reach a destination.Purpose implies mind, and this convinced Socrates there must be some

ultimate mind behind the world’s organization. Yet the intellectuals

who proposed an ultimate mind, such as Anaxagoras, left Socrates

unsatisfied. This motivated Socrates to seek out answers for himself,

and thus western civilization was born.Let’s imagine common theology exists. In fact, we don’t have to

imagine. Common theology exists whenever anyone starts thinking about

the ultimate nature of our world for themselves. One of the common

conclusions people reach when they start wondering about such things

is similar to Socrates’ conclusion: there must be an ultimate mind

responsible for our world. The only minds that we know of are our

own, so it makes sense to see what we can figure out about the

ultimate mind based on our own minds.Within our minds we note at least three basic things. There is the

mind itself, the ideas in the mind, and the emotions. Within our

human minds, these are different parts of our mind. Yet, that makes

us imperfect, since that means the parts have to come from somewhere

outside of ourselves. We don’t create our own minds. We are only

partially responsible for our ideas and emotions, and they often seem

to have lives of their own.What does this say about the ultimate mind? If the ultimate mind also

has ideas and emotions like we do, then the ultimate mind cannot be

truly ultimate, since its ideas and emotions have their own existence.

Along with the ultimate mind, there also has to be ultimate ideas and

emotions alongside the mind. From this perspective, we end up with a

world populated by many sorts of ultimate things, as many ultimate

things as there are ideas and emotions, governed by an ultimate mind.Yet this sort of notion does not quite make sense. We originally set

out to achieve an ultimate understanding of our world. The core

intuition is there should be some sort of theory of everything, some

origin for it all, some unifying principle. Instead, we ended up with

even more complexity than when we started, with way too many ultimate

things, and even more questions as to where all these things came

from. This way of thinking ends up being exhausting.One solution people have tried is to say all the complexity is an

illusion. The only thing that really exists is the single mind. This

answer makes some amount of sense. At least it preserves the simple

origin that we set out to discover. At the same time, I’m pretty sure

the kitchen cabinet door that keeps jabbing me in the head exists.Yet another way is to just insist there is an ultimate mind, and say

its nature is completely beyond our understanding. This approach also

has merit. Obviously, the ultimate mind is really great compared to

ours, and it is obvious we cannot understand everything. However,

there is a difference between completely not understandable versus not

completely understandable. Just like we cannot believe in square

circles and married bachelors, things that are completely not

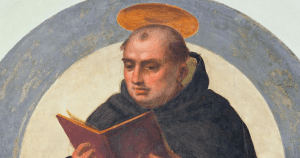

understandable do not mean anything.A better solution is offered by one of history’s greatest common

theologians, a medieval monk named Aquinas. He states the ultimate

mind is not different from its ideas and emotions. They ideas and

emotions are all the same fundamental thing as the ultimate mind.

This is because the ultimate mind is existence itself, so its ideas

and emotions cannot derive their existence from anything outside of

the mind. In this way, Aquinas explains there are three distinct

things in one ultimate mind, without falling into the problem of too

many ultimate things.Aquinas’ idea is groundbreaking in the history of theology. Previous

approaches to common theology ended up stuck in the dilemmas above

that ultimately lead to too many ultimate things. Aquinas’ idea is

the first understanding of the ultimate mind that did not result in

too many ultimate things. However, today his breakthrough is not wellunderstood. Most modern theologies do not recognize the dilemma of

explaining how the ultimate mind can create the world, while preserve

the reality and distinction of both. Instead, modern theologies

reject either the ultimate mind, or insist it is totally alien to our

own self understanding.These theological divisions lead to major disagreements today. If we

were to hop on board a time machine and bring Aquinas’ brilliance back

to our day, this would go a long way to resolving the disagreements we

face today. The first step in our trip back in time is to recover the

joy of common theology.