Poetry

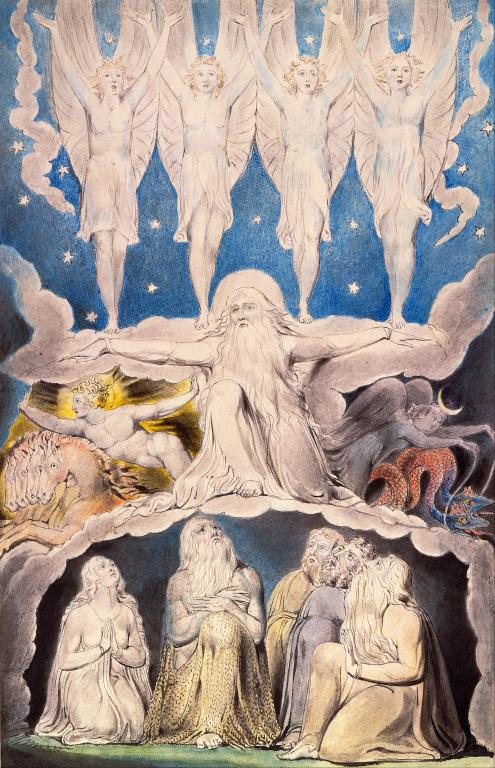

This section is wonderful, I must admit. Martin here has collected poetry and prayers and poetic reflections (that is prose that has a poetic feel to it) that all, to one extent or another, reflect the sophianic, that is the porousness of reality or the closeness of God to creation. While I critiqued the primary sources section for lacking patristic or medieval sources, some medieval sources can be found here. Saints Patrick, Hildegard, and Francis as well as Dante all make appearances. However, the Middle Ages are quickly left as jump to the 16th/17th century and beyond. Rather than offer reflections or commentary on the poetry, Martin allows it to stand on its own. The poetry works on the reader, embedding us in it rather than simply telling us about it.

It is from a poem in this section, “The Heavenly Country” by Robert Kelly, that the book receives its title. In this poem, Kelly reflects on this place he has encountered throughout his life. Kelly has encountered this place on a family holiday; in the England of Milne and Tolkien and Chesterton and Wordsworth and Blake. He writes:

Certainly I needed the place. Perhaps I even used it well, husbandman of a land I’ve never entered. I think those intimate landscapes lie behind my perceptions and registrations of nearer or ‘realer’ country; sometimes they show through, when yearning or demand overpowers me looking at, say, the big field down Tarrytown with the mountains low beyond if. Not this field, the mind whispers, but a field just like it somewhere else, no lovelier at all, but there (264).

It reminds me of Lewis’ description of the Joy he had encountered throughout his life; the joy in pursuit of which he was led, unwillingly, to Christianity. It also reminds me of The Last Battle by Lewis where the friends of Narnia find themselves in a country only seeing landscapes that remind them of Narnian ones only different, in this case actually lovelier. This is the heart of this book, or so I am led to conclude since this poem gave the book its title. It is this poetic or sacramental imagination that sophiology engenders. Wisdom is bound up in creation, reflecting the divine to us, when we see rightly, and us in the divine. Sophia becomes a Lady of Faërie, showing us that there are no boundaries between our world and Faërie only distorted sight.