On Saturday, Jana Riess posted a piece on her Religion News Service blog raising questions about whether, in a recent blog post about the feminization and sexualization of characters in the Candy Land board game, writer Peggy Orenstein used images and ideas, without attribution, from blogger Rachel Marie Stone’s post on the same topic. Jana raises three red flags: 1) the fact that Orenstein used three of Rachel’s images without permission or attribution, 2) the similarity of language/terminology between the two writers’ posts, and 3) a factual mistake that Rachel made in one of her posts that Orenstein also made in hers.

When Rachel and others first raised questions about sources for Orenstein’s post, Orenstein admitted to hasty and improper use of Rachel’s images, which she says she obtained via a Google search, and made appropriate corrections. She denies reading Rachel’s posts on the topic, much less using Rachel’s ideas without attribution. If you haven’t read Jana’s analysis of the similarities between Rachel’s and Orenstein’s writing and the questions they raise, I suggest you do so before continuing with this post.

When Rachel and others first raised questions about sources for Orenstein’s post, Orenstein admitted to hasty and improper use of Rachel’s images, which she says she obtained via a Google search, and made appropriate corrections. She denies reading Rachel’s posts on the topic, much less using Rachel’s ideas without attribution. If you haven’t read Jana’s analysis of the similarities between Rachel’s and Orenstein’s writing and the questions they raise, I suggest you do so before continuing with this post.

You’ll note that I am referring to Rachel and Jana by first name, and Orenstein more formally, by last name. That’s because Rachel and Jana are colleagues and friends, while Orenstein is not. Clearly, I have much more insight into Rachel and Jana’s character and motivations than Orenstein’s—a limitation and bias that I will admit up front.

Rachel is a close friend, and I recently wrote about her new book, Eat with Joy. Jana Riess is also a friend, author (of the award-winning book Flunking Sainthood, among others) and blogger. She also edited my book, No Easy Choice. Peggy Orenstein is the author of several books, most recently Cinderella Ate My Daughter, an acclaimed indictment of the pink-infused, princess-dominated “girlie-girl” culture in which our daughters are growing up. I haven’t read Cinderella, but I have read much of Orenstein’s other work. In my book, I quoted cogent observations about fertility medicine and cultural attitudes toward miscarriage and abortion from her memoir, Waiting for Daisy. I have read and deeply appreciated many of the articles she has written for the New York Times magazine, including this week’s cover article about whether wildly successful efforts to increase breast cancer awareness and screening have done more harm than good. (In fact, I will discuss this article more in a post later this week, drawing on my experience of having a specific type of breast cancer that Orenstein addresses at length.)

In conversations with me, Jana, and others on Twitter, Facebook, and her blog post, a clearly annoyed Orenstein has suggested that perhaps Rachel’s writing on this topic was inspired by her, not the other way around. (Rachel has never heard Orenstein speak, and as far as I can tell, this is the only piece Orenstein has written that addresses these specific concerns about Candy Land characters in detail. Later in this post, I provide links to two of Orenstein’s posts that are tangentially related to the Candy Land post.)

After Jana posted her concerns, Orenstein made significant changes to her post as it appeared on her own blog. She acknowledged the controversy, reiterated that she has talked and written about the skinnified, sexualized evolution of children’s toys for a number of years, and referred readers to Rachel’s blog and images, writing, “Mine was neither the first nor the definitive word on any of the issues I covered. Our voices all play a role in change.” In the post as it appeared in adapted form on The Atlantic’s “Sexes” blog, those changes do not appear, although she did add a sentence indicating that she is not the only one writing about Candy Land characters’ evolution and linking to Rachel’s blog.

So is this controversy over? I am guessing that Orenstein believes and hopes it is. I know that Rachel is still hurt, confused, and uncertain. I’d like to offer a few more insights to indicate why I believe some legitimate questions remain.

The question is whether Orenstein, intentionally or not, borrowed ideas and language from Rachel’s writing without attribution. The question is not whether Orenstein only came up with the idea of critiquing Candy Land characters after reading Rachel’s post. In a comment on her blog, Orenstein wrote, “maybe smart people who are working in the same area notice things.” Absolutely true. She reminds readers that her focus for many years has been on the sexualization and “princess-ification” of girlhood, which leads her to examine how children’s toys echo or support this trend. She has indeed mentioned Candy Land in previous blog posts (such as this one) and has written about manufacturers revamping other classic toys to make them thinner and prettier.

No one is arguing that Orenstein never noticed the thinning and prettying of children’s toys, and of Candy Land characters in particular, until she came upon Rachel’s work in this area.

Rather, the question is whether the language that Orenstein used in last week’s posts on her own blog and The Atlantic echoed Rachel’s writing on the same topic to a questionable extent.

Orenstein has admitted that she took images from Rachel’s blog via a Google search without attributing them—a mistake that she says occurred because she was in a hurry and was “sloppy.” This is a plausible explanation. While bloggers should not publish images obtained via Google search (we only have permission to publish images that are made publicly available via a Creative Commons license), it happens all the time. Even so, three out of four close-up images in Orenstein’s original post were from Rachel’s blog, and published in the same order. A Google search for “Candy Land” returns 200 million images, and Rachel’s are not the first ones to show up. (Update: In the comments below, Rachel’s husband Tim Stone provides details that make the notion that Orenstein used three of Rachel’s images by accident because she did a hurried Google search less and less plausible.)

But the more significant question causing Jana’s, my, and other readers’ discomfort is whether, in addition to using those images, Orenstein might have read Rachel’s post and, consciously or not, echoed her word usage and presentation of ideas to an unacceptable extent.

What if we look at the two writers’ posts through a textual criticism lens—a technique whereby scholars of biblical and other literature examine texts to suggest the writer’s source material, by looking not simply at whether writers discuss the same ideas, but how they discuss those ideas? By looking carefully at a writer’s word choices, sentence structure, order of events/examples, and choices about what to emphasize, and comparing those choices with other sources, textual criticism can show to what extent a writer’s work is influenced by the work of other writers.

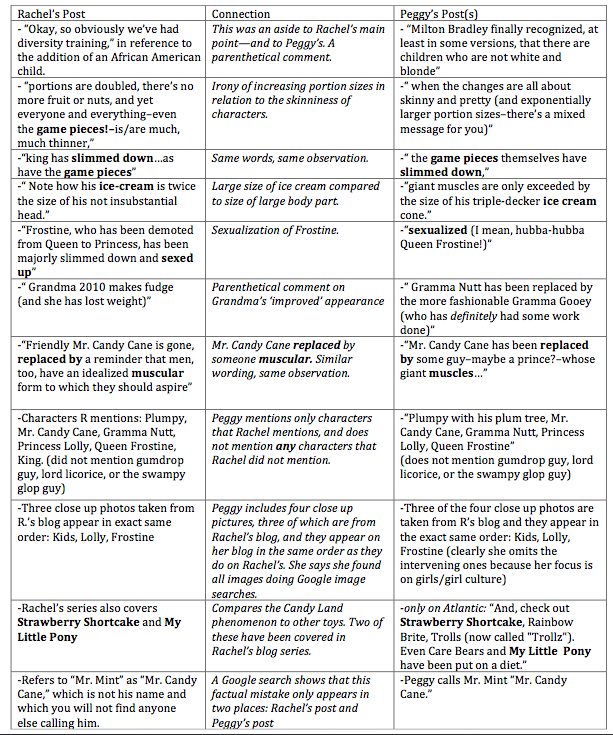

Rachel, who studied textual criticism for a master’s in literature, and her husband Tim, who is a biblical scholar with textual criticism expertise, came up with the following chart comparing Rachel’s Candy Land post with Orenstein’s (before any edits, which didn’t change most of what is in this chart in any case):

I agree with Jana that “the similarities are striking, but in no way definitive.” I also agree with Jana that the repetition of the mistaken name for Mr. Mint is much harder to dismiss as coincidental.

Is it possible that their mutual mistake, and the other textual similarities, are mere coincidence? Yes, it is certainly possible. Mr. Mint does, after all, wear red-and-white striped clothing. Oh, how sorely I wish that this controversy involved a different subject. It’s hard to raise serious questions while parsing the nomenclature and clothing of candy-themed cartoon characters. (Update: A commenter on Jana’s blog lists several other instances of people using the Mr. Candy Cane misnomer for the Mr. Mint character, noting that “it’s not the most common mistake in the world. But it’s also not at all original.”)

However, as someone who reads dozens of blog posts every day on topics similar to my own, I am frequently amazed by how writers addressing the same topic, even from a similar perspective, often do so with a great deal of originality, using very different language, examples, and emphases to illustrate similar concerns. I find the similarities between Rachel’s and Orenstein’s posts unusually consistent, even for two smart women who are both interested in critiquing cultural notions of what is attractive and feminine.

Is it a weensy bit over the top to look at two blog posts on a children’s board game with textual criticism techniques that are usually reserved for biblical and other classic literature? Perhaps. But consider Rachel’s position upon initially discovering (courtesy of an astute colleague) the similarities between Orenstein’s post and her own, as well as the unattributed images. Here she is, a relatively new author, her first book just released, working hard in a crowded market to get page views, readers, and editorial interest. Here is a topic she has covered extensively; Rachel has written numerous posts on a variety of iconic toys that have gotten sexy, skinny makeovers. So many people landed on her blog after using the search terms “Rachel Marie Stone skinny toys” that she devoted an entire page of her site to the topic. Rachel can reasonably argue that no one has addressed this topic to the extent she has. This expertise is an important tool as she works to convince editors and readers that her voice deserves to stand out in the bloated blogosphere.

And then, a writer who is already recognized as a unique, authoritative voice writes an article on the same topic, employs words and examples that are remarkably similar to hers, uses three of her images without attribution, and the post gets picked up by The Atlantic—and then dozens and dozens of other news outlets and blogs.

Ouch.

Of course, Peggy Orenstein’s platform and authority didn’t happen by magic. Presumably, she was once where Rachel is now. She was once a writer with talent, insight, and a compelling voice who was still working to prove to editors and readers that she deserved their attention. She likely got to where she is now the same way most successful writers get where they are—years of hard work to improve her writing and get her name “out there,” coupled with a few lucky connections.

If Orenstein remembers what it felt like to be where Rachel is now, this incident is an opportunity for her to extend grace to a writer who is understandably concerned by compelling, if inconclusive, evidence that her work might have been used inappropriately by a writer of greater stature.

Some of Orenstein’s edits to her original blog post, crediting Rachel’s work, are indeed gracious, and I appreciate that. Nevertheless, legitimate questions remain. And some of Orenstein’s other reactions to this incident are distinctly ungracious. In a Twitter exchange with Jana, she wondered whether this controversy is a self-promotion stunt on Rachel’s part. In addressing it on her own blog, Orenstein wrote:

I don’t think of blogging the way I do my articles and books in terms of journalistic standards, mostly because it seems bloggers themselves don’t.

This is a troubling admission. I’m not sure of which bloggers she is speaking. There are many bloggers out there, many of them not particularly original or consistent, and far from professional. But many professional bloggers, like me and Rachel and our colleagues—writers who don’t yet and may never have the opportunity to write best-selling books and New York Times magazine cover articles, who write, often for free, on our own blogs and others’ because we are compelled to pen words that other people will read and appreciate, who are driven to contribute to public discourse on issues of concern for our culture, our communities, and our children in spite of low or nonexistent pay and the continual fight to be heard in the online cacophony—hold very high standards for our work.

If the similarities between Orenstein’s posts and Rachel’s are truly due to remarkable coincidence, then Orenstein’s response on her own blog was adequate, if not entirely satisfying. I would like to see her post at The Atlantic likewise edited. I have written this largely to defend Rachel’s reputation as a writer of integrity. This controversy is not a publicity stunt. It is an understandable effort by an up-and-coming writer, and her fans and colleagues, to defend her expertise and show that reasonable questions remain as to whether a more accomplished writer inappropriately, perhaps unintentionally, borrowed from her work. I hope that my and Jana’s posts, as well as Orenstein’s edits pointing readers to Rachel’s blog, lead readers to more fully appreciate Rachel’s quality work on this and other topics.