Note: This post is not a book review, but a discussion of ethical questions raised by the story told in Holding Silvan: A Brief Life by Monica Wesolowska. It is full of spoilers.

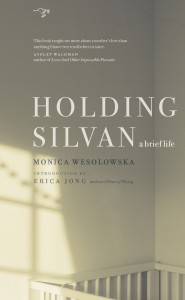

In her memoir Holding Silvan: A Brief Life, Monica Wesolowska conveys two primary facts—first, that she loved her son Silvan deeply, and all decisions about his living and dying were motivated by that love, and second, that the decision she and her husband made to withhold nourishment from Silvan was not euthanasia. I am absolutely convinced of the first, but not as much of the second. I admire Wesolowska’s skill, I’m grateful for her honesty, I’m sympathetic to her decisions. And I’m not entirely convinced by her justifications for those decisions.

I have avoided writing this post for weeks. What sort of person questions a parent who made agonizing decisions about her child in a nightmare situation? I do, I guess. But I do so with as much compassion and empathy as I can muster. I want to honor Wesolowska’s story as the precious gift that it is. I have devoted a good portion of my career to parsing difficult questions around what Erica Jong, who wrote the book’s introduction, calls “damaged children”—children with significant disabilities. I am devoted to conversations around the choices parents make about whether to bear and/or raise such children, and the judgments we make as individuals and a culture about the value of such children’s lives. Wesolowska deliberately joins these conversations in Holding Silvan, going beyond the facts of her family’s story to consider cultural and medical attitudes toward death and suffering. Wesolowska offers her story as a vehicle for asking larger questions about suffering, love, and the way we die. I am responding not solely to her story as she tells it, and the decisions she made, but to her framing of her story in relation to those questions—a framework that I found deeply flawed.

I have avoided writing this post for weeks. What sort of person questions a parent who made agonizing decisions about her child in a nightmare situation? I do, I guess. But I do so with as much compassion and empathy as I can muster. I want to honor Wesolowska’s story as the precious gift that it is. I have devoted a good portion of my career to parsing difficult questions around what Erica Jong, who wrote the book’s introduction, calls “damaged children”—children with significant disabilities. I am devoted to conversations around the choices parents make about whether to bear and/or raise such children, and the judgments we make as individuals and a culture about the value of such children’s lives. Wesolowska deliberately joins these conversations in Holding Silvan, going beyond the facts of her family’s story to consider cultural and medical attitudes toward death and suffering. Wesolowska offers her story as a vehicle for asking larger questions about suffering, love, and the way we die. I am responding not solely to her story as she tells it, and the decisions she made, but to her framing of her story in relation to those questions—a framework that I found deeply flawed.

Wesolowska and her husband’s first baby, Silvan, was without oxygen long enough, sometime during his birth, to cause catastrophic brain damage. With Silvan in a coma, his parents learn that he likely only has brain stem function, with no higher brain function. As she struggles to understand what has happened to her baby, Wesolowska also begins to understand that “already many choices have been made about his life without my knowledge.” Silvan was revived with oxygen after his birth. Their doctor reminds the parents that they couldn’t have just let the baby die at birth without knowing what was wrong. The doctor also tells them that some parents with such severely brain-damaged babies will allow them to die of pneumonia or seizures. Wesolowska asks if there is any other way to allow Silvan to die.

And so, he tells us. He tells us that in the case of a newborn with a prognosis as grim as Silvan’s, coupled with a coma and inability to take nourishment orally, it is legal to withdraw all food and liquid. I have no memory of this moment, the shock of learning the truth that, though euthanasia is illegal, you can starve a person to death….What I remember instead is that one moment I am in despair for Silvan, and the next I have hope.

Wesolowska goes on to beat a familiar (and important) drum about how Western medicine is so consumed with keeping people alive via technology that we don’t know how to help people die well. Given the situation as she has described it thus far—a comatose baby with catastrophic brain damage—the initial decision to withhold life support, including nourishment via technological means (IVs and feeding tubes), and allow Silvan to die does indeed seem like the compassionate thing to do.

Except that Silvan does eventually exhibit a desire to suck. His parents and nurses soothe him with their fingers, but no one suggests he try to nurse. In light of this fact and his parents’ continued adherence to their decision to withhold all nourishment, some of Wesolowska’s pondering about suffering, mercy, and death gets a little confused.

When Silvan’s grandmother asks whether they are absolutely certain of Silvan’s prognosis, Wesolowska replies that they don’t know, “but to gamble otherwise seems unfair to Silvan.” I wonder why they didn’t see withholding food from a child who could potentially eat as an equally unfair gamble. I wonder why they perceived a life of severe disability, but not certain death from starvation, as unfair.

Wesolowska writes,

I find the mother in me wants to believe that if Silvan can now suck, then he can eat, and if he can eat then perhaps he needs to be offered food. As in one of my childhood fantasies about sainthood, I want to believe if I only love him enough, he will learn to eat, go off to school, get Bs and Cs. I could write a book.

I wonder at the leap of logic in those sentences, at a mother who pulls back from her desire to feed her child because feeding him wouldn’t transform him from the child he is into the child she wants him to be. As I read this, she wants to feed him but won’t because it doesn’t change the prognosis enough. The writer in me is also sympathetic, but also bothered, by how often Wesolowska mentions the book she could write. That she, in fact, did write.

Wesolowska says several times that Silvan tried to die when he was born, and “has been trying to die” ever since. I wonder why she ascribes such an act of will to a newborn when it comes to his dying but not to his wanting to suck and eat.

Wesolowska reflects that, “So far [Silvan] hasn’t even known the discomfort of eating, gagging, gas, poopy diapers. All he’s known in life is love.” And yet, I wonder, isn’t this where love happens for human beings, in the midst of discomfort and pain and shit of all kinds?

The author and her husband continually say that their decision to withhold nourishment is meant to ease Silvan’s suffering, to ensure that all he knows in his brief life is love. I think of how feeding our children is a primary way that we love our children. When we feed our children, we believe they can feel our connection, our devotion, even if they cannot name it. Then I read a scene in which the young parents discover one day at home, where they have brought Silvan to die, that his mouth is caked with a stinking mass of saliva and the remnants of the morphine he gets for comfort. And I wonder, isn’t this—a mouth clogged with gunk tainted by the drugs he gets to ease his death by starvation—suffering? Why don’t they want to free him from this suffering too?

Wesolowska continually conflates the artificial prolonging of life through technology with their decision to withhold nourishment from a child who might, indeed, be able to eat. She writes, “in the twenty-first century, medicine has progressed to a point that most people in the United States no longer die of a disease. Instead, most people die of a choice top stop treating whatever disease they have.” This is true, but Wesolowska and her husband did not choose to stop treating Silvan’s medical problems. They chose not to feed him.

Although Wesolowska’s mother is initially uncomfortable with the couple’s decision to withhold nourishment, the only person in the story who states a clear objection is a friend, Brian, who asks, “Why don’t you let [Silvan] die of pneumonia or something else more natural?” It’s a clumsy way of asking a key question: Why not choose to withhold treatment if and when a life-threatening event (such as pneumonia or a seizure) comes, instead of ensuring Silvan’s death by withholding nourishment? But Wesolowska never seriously engages with the question, instead framing her decision as a bucking of “new technologies” that cause patients to be “pushed to the edge of what some would consider life”—even though withholding nourishment is not equivalent to refusing medical interventions to prolong life. Brian is one half of a married couple whom Wesolowska portrays as particularly tone deaf to their suffering. Brian’s wife, Claudia, goes on and on about her own uncomfortable pregnancy symptoms, for example. I wonder if her friends’ inability to offer the kind of love and support Wesolowska and her husband needed made it impossible for her to hear the relevant question Brian asked, or if, conversely, his asking this uncomfortable question contributed to the two couples’ estrangement.

In several courageously honest passages, Wesolowska explains that, while they were concerned that Silvan not suffer, they were also concerned with the “threat to our marriage” that a severely disabled child would be. Her husband David thought of a disabled cousin who required her parents’ lifelong care and attention. “You wouldn’t really want to do that,” David persists softly, earnestly. “You wouldn’t really want to devote your life to him, would you?” And Wesolowka admits, “We believe that Silvan should be allowed to die not only for his sake but for all of ours.” Our culture loves to portray the parents of disabled children as selfless saints, which exacerbates our failure to provide adequate respite care and support services to families caring for severely disabled children and adults. I admire the author’s and her husband’s honesty, both in having these conversations and relating them to readers.

But these conversations also complicate Wesolowska’s stated justifications for their decision. She tells the hospital ethics committee that their primary motivation is to ensure that Silvan know “nothing else but love” in his brief life. She emphasizes that no one knows what Silvan will or will not do—whether he will be able to eat or drink, whether he will succumb to pneumonia or seizures or stop breathing at random times. I wonder why the preferred response to not knowing how Silvan and his family will suffer is to ensure that he dies sooner rather than later. I wonder why no one pointed out that, just as they could not predict what trials would be ahead for Silvan and their family, they could also not predict moments of contentment or even joy, moments when they might know deep gratitude for Silvan’s being alive and part of their family, even with his profound disabilities.

In her book Knocking on Heaven’s Door (which more directly and fully engages with questions around prolonging of life and avoidance of death), Katy Butler writes that historically, “the hallmark of a good death was not an absence of suffering, but the ability to meet it with faith, courage, and acceptance.” Wesolowska and her husband seemed to believe that meeting death with faith, courage, and acceptance meant protecting their son, and themselves, from the potential suffering of a child living with a severely compromised brain and body. I wonder if meeting death with faith, courage, and acceptance might instead have meant giving Silvan a chance to live—and die—according to his body’s dictates. Instead, he lived and died according to his parents’ assumption that a life marked by love is one as free of suffering and uncertainty as we can possibly make it. The hospital ethics committee, along with many of Silvan’s caregivers who lauded his parents’ decision as brave, also appeared to make that assumption—which is not a surprise given how our medical and wider cultures frame disability, as well as death, as a tragedy to be avoided at all costs.

The irony in Wesolowska’s story is that she aptly names and observes our cultural fear of death, but fails (along with the medical professionals involved in Silvan’s care) to examine the assumptions at the core of our equally powerful fear of physical and cognitive dysfunction. Our tendency to push death away with ever more sophisticated technology arises from the same impulse as our sense that a severely compromised child is better off dead—our aversion to the extremes of pain, limitation, and uncertainty to which human bodies are subject, our assumption that the depths of pain and loss should be avoidable. This assumption leads us to believe that bodies subject to pain, disability, and limitation ought to be either heroically rescued from or hastened toward death, rather than abided as they are, in their living and their dying.

Author’s Note: (added post-publication): Monica Wesolowska informed me via tweet that Silvan could suck but not swallow—a fact that was not clear in her narrative. Does that change my perspective on her story? Yes and no. It does make the decision not to attempt to feed him via breast or bottle much more obvious. I continue to be troubled by the conflation of withholding nourishment with extreme technological interventions to postpone death. I think that providing palliative hospice-type care to a severely ill newborn is preferable in many situations to subjecting a child to invasive treatments in the hope of some kind of miracle recovery. But I didn’t read this family’s choice as being one between extreme intervention to foster vain hope and palliative care; nothing in the narrative indicated that anyone was suggesting that they subject Silvan to any kind of heroic treatments. Rather, the choice seemed to be between certain death by starvation and a far less certain outcome if Silvan lived. However, as I told Wesolowska, I also understand that true stories have layers that cannot always be conveyed in words. I maintain that our tendency to fight death with any and all interventions and our tendency to believe that life with disability is not worth living are two sides of the same coin. And while I was hesitant to publish this because of how much I don’t want to question another parent’s choice, I did so because I am convinced that we need to do a much better job of talking about these sorts of issues, starting with being clear on what questions we are actually asking. Monica Wesolowska may no longer need this kind of clarity, but the rest of us do, particularly the medical professionals who provide front-line care to families facing these agonizing choices.