One of my favorite scriptures—I suspect it’s a favorite for many of you as well—is Matthew 25: 31–46:

When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family,[g] you did it to me.’ Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You that are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels; for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’ Then they also will answer, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not take care of you?’ Then he will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.

“The least of these”—such an evocative phrase, speaking directly to Jesus’s tendency to turn humankind’s most treasured notions on their head. Cultures throughout history, including Jesus’s and ours, have assumed that those with more—more power, more money, more prestige—are the ones who most deserve our attention. And here Jesus is saying nope, it’s those with less, those who occupy the least powerful, least noticeable rungs on culture’s ladder who deserve our attention. Those who are hungry, naked, imprisoned, vulnerable.

He goes a step farther to say that these vulnerable people aren’t merely co-citizens of the world who need our help, but that they are Jesus himself. Christians are fond of saying that we are Christ’s hands in the world. But in Matthew 25, Christ’s hands are not the ones offering a cup or a meal or a coat; Christ’s hands are the ones reaching out in desperate need to be filled.

Over and over, in both Old Testament and New, we are told that the most fundamental way we express our faith is through caring for those in need. The prophet Micah wrote, “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8). When asked to boil all of God’s laws into one central idea, Jesus said, “ ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22: 36–40). Of course, just what it looks like to “love your neighbor as yourself” is regularly and hotly debated; people have very different ideas of how we should love those who are poor or hungry or in prison. But that we must love and give to those in need—and not just people we know and love (Matthew 5:46-47) and not just those we identify as belonging to our “tribe” (Luke 10:30–37)—is a foundational tenet of Christian faith.

Over and over, in both Old Testament and New, we are told that the most fundamental way we express our faith is through caring for those in need. The prophet Micah wrote, “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8). When asked to boil all of God’s laws into one central idea, Jesus said, “ ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22: 36–40). Of course, just what it looks like to “love your neighbor as yourself” is regularly and hotly debated; people have very different ideas of how we should love those who are poor or hungry or in prison. But that we must love and give to those in need—and not just people we know and love (Matthew 5:46-47) and not just those we identify as belonging to our “tribe” (Luke 10:30–37)—is a foundational tenet of Christian faith.

Or at least, I thought it was.

When my friend Caryn wrote this post for Christianity Today on our responsibility to prisoners, she learned that the magazine has entertained an alternate interpretation of Matthew 25 in which “the least of these” refers not to any person in great need, but exclusively to Christians persecuted for their faith. A number of evangelical theologians have publicly embraced this interpretation, which they say is an ancient one that deserves to be resurrected. (You can read more about this interpretation here and here.)

All of us, even those who claim that the Bible is an inerrant document providing a crystal-clear road map for believers, engage in interpretation when we try to figure out what a Bible passage is telling us. Those who interpret “the least of these” as persecuted Christians rather than any people in desperate need provide thoughtful evidence for their take. Fair enough. But when confronted with such different interpretations of a key scripture, we must consider how each interpretation fits into the larger biblical narrative, and whether its implications mesh with what the overall narrative tells us about the nature of God.

Interpreting “the least of these”—those who embody Jesus and for whom we are called to care—as fellow Christians facing persecution, rather than any hungry, thirsty, or imprisoned person, is a dangerous claim that doesn’t fit with the rest of the biblical narrative.

This interpretation is dangerous because it implies exclusivity and tribalism—that Jesus only calls us to sacrificial care for people like us. In contrast, the New Testament repeatedly portrays the way of Jesus as one of boundary-breaking inclusivity. Jesus portrays a reviled Samaritan as a hero and invites marginalized people into full participation in his ministry, including women, children, lepers, and “tax collectors and sinners.” Paul argues that the good news of Jesus Christ is meant for Gentiles, not just Jews, and proclaims that in Christ, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” (Galatians 3:28).

Jesus’s great commandment to love God and love neighbor is not easy, but it is simple. Jesus made concrete acts of love for “the other” a defining mark of his life and ministry.

Furthermore, if we’re called to sacrificially serve only a particular subset of humanity, rather than any human being in great need, our inevitable next step is to figure out who occupies that subset. I recently read a blog post by a Christian who claims that the most important question of our lives is where we will spend eternity—in other words, whether we will be saved because we subscribe to a specific set of beliefs that this blogger believes are necessary if one wishes to abide happily with God in eternity instead of being subjected to the torment of hell.

But Jesus—unlike many faithful people of both his day and ours—wasn’t particularly concerned with figuring out who is “in” and who is “out,” who is saved and not saved, who does and doesn’t follow the law correctly. Jesus put care for people above law and labels, above tradition and taboos. Jesus didn’t go around asking people if they know the Four Spiritual Laws and accept him as their savior, or asking if they know where they will spend eternity.

Instead, Jesus asked questions like, “How hard will it be for those who are wealthy to enter the kingdom of God?” (Mark 10:23), “Which of these was a neighbor to the one who was robbed?” (Luke 10:36), “Who is my mother? Who are my brothers?” (Matthew 12:48—one of the most shocking verses indicating that Jesus meant to upend cultural notions about our primary allegiance being to those within our tribe, those with whom we have a natural affinity because they are like us), and most simply, “Do you love me?” (John 21:16). Note that when Peter said yes, I love you, Jesus didn’t say, “Then go preach the four spiritual laws to your friends and family to ensure that they are in heaven with you” but rather, “Feed my sheep.”

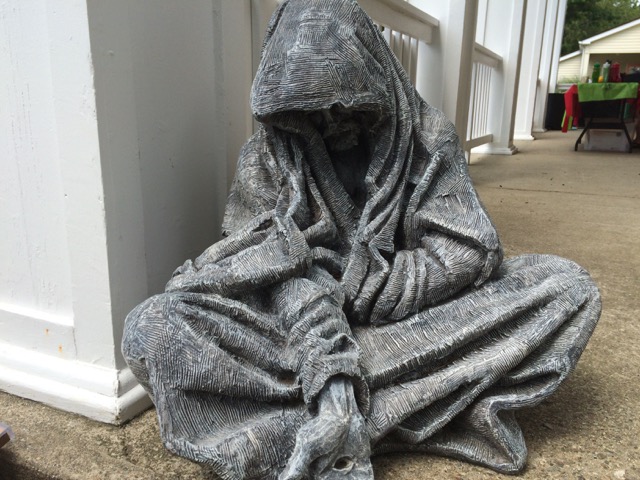

The sculpture pictured above is currently sitting on the porch at my kids’ Episcopal summer camp. If you look closely at the beggar’s outstretched hand, you can see a hole there; it is Christ’s hand, marked by the nails of his crucifixion. Titled “Whatsoever You Do,” this sculpture is, according to its creator Timothy P. Schmaltz, “a visual representation of charity. We should see Christ in the poor and the hungry. We should see our acts of kindness to them as kindness to Him. It is inspired by the Gospel of Matthew 25:40.”

Christians will always disagree on exactly how to interpret scripture; such questioning is inevitable for a faith guided by an ancient book with far more stories than edicts. But which interpretation is more likely to inspire us to love our neighbor, to do justice, to walk humbly (emphasis on “humbly”) with our God? The interpretation that draws a line between those who have the right answer to how to live a righteous life and those who don’t, and reassures us that we are only responsible for radically loving those who have the right answer, as we do? Or the interpretation that says that every time we turn our face away from someone in desperate need, we are turning away from God?