The Dutch press is reporting a new study with an international perspective on what drives church attendance (the authors are Stijn Ruiter, senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, and Frank van Tubergen, a professor of sociology in Utrecht).

What they set out to do was to compare the major theories on what causes religion, using data from the World Values Survey and other sources. Broadly speaking, you can summarize these theories like this:

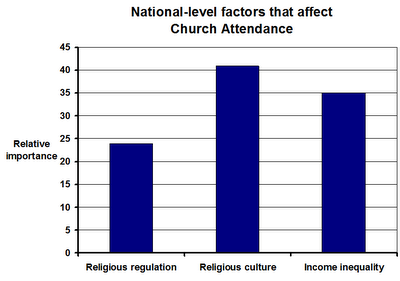

- Religious regulation: a close relationship between state and church tends to turn people off it.

- Education: better educated people abandon religion

- Economic security: if people don’t have to worry about their future, gods lose their appeal.

- Individualization: religion is a social phenomenon, and people are only religious because everyone around them is.

What Ruiter and van Tubergen did was a multi-level analysis. In other words, they looked at the characteristics of individuals and compared them with their churchgoing habits. And they also looked at the characteristics of nations, and looked to see what effect that had on individual churchgoing.

This multilevel analysis is a very powerful. But one downside is that it needs a lot of data, and the sort of data it needs aren’t available for a lot of countries. In fact, it’s mostly available only for rich, Christian countries. Still, they included 60 in their analysis, which is quite a pool.

By far and away the strongest predictor of how often a person goes to church is whether they had religious parents. That’s not too surprising. But what is surprising is that, even after controlling for that effect, one of the most powerful predictors is how religious everyone else’s parents are. In other words, one of the major deciding factors in whether or not you go to church is whether you grew up in a religious country.

Another important factor was religious regulation. In countries with a strong state interference in religion, attendance goes down. Other studies suggest that’s probably because when people feel pressured into going to Church, they don’t enjoy it.

One thing that didn’t have much effect was education. There was no clear effect of average education in a country. But there was a slight effect of individual education – more educated people are slightly less likely to be churchgoers. That’s probably because education is double-edged when it comes to religion. It decreases beliefs, but it also increases ‘community-mindedness’. In other words, educated people tend to get involved in community activities.

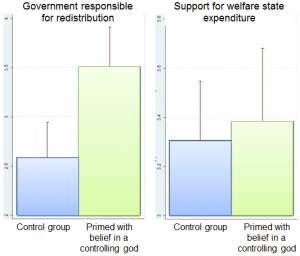

The final factor was income inequality. In line with other studies, they found that both income inequality and low state welfare spending are associated with more religion:

…we find that attendance rates are particularly high in countries with more socioeconomic inequalities and fewer social welfare expenditure. This effect equally applies to both poor and rich people, which is in line with the idea that because of economic mobility and the possibility of unemployment in the (nearby) future also the more affluent population feels more insecure in countries with more inequalities and without a well-developed social welfare system.

We also see that people with a lower income and who are unemployed attend religious meetings more often, and we find an enduring effect of growing up in times of war. In summary, the results of our study suggest that personal and societal insecurities play a crucial role in explaining cross-national variation in religious attendance.

Now this is particularly interesting because it backs up what I found in my own study, published earlier this year. In that study, I looked (in a rather simpler analysis) at the country-level factors that correlate with how often people pray. I found that income inequality was one of the strongest.

So the two studies complement each other. Religious attendance and religious belief are related, but they are not the same. At yet both these two key aspects of religion both decrease in countries with strong social systems where people have less to worry about.

But by now people have probably spotted the potential flaw, which is shared by all these kinds of correlational studies: correlation does not mean causation! So which is it? Does inequality really lead to more religion? Or could it be that religion causes inequality?

That’s a good question – and it’s a topic for the next post!

Hat tip: David Flint of Humanists4Science.

__________________________________________________________________________![]()

Stijn Ruiter, & Frank van Tubergen (2009). Religious Attendance in Cross-National Perspective: A Multilevel Analysis of 60 Countries American Journal of Sociology (November)

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.