Different sounds accompany great disasters. An earthquake begins with the rumble of heaving earth and the crack of fissured faults, followed by the cacophony of books falling off shelves, dishes clattering to the floor, roofs collapsing, and houses sliding off their foundations. A tsunami’s whoosh is quieter, but far more deadly: the ocean itself rises up to wash away automobiles, trains, forests, and entire towns. Radiation from a nuclear meltdown makes no sound at all, yet somehow the silence amplifies the fear.

Fukushima

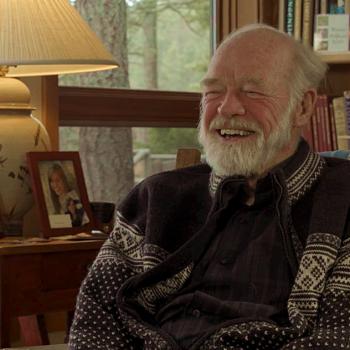

In 2012 I toured the devastated area of Japan on the one-year anniversary of the earthquake and tsunami that caused some 19,000 deaths and destroyed or damaged a million buildings. (I wrote about that visit in the book The Question That Never Goes Away.) Last month, seven years after the triple catastrophe, I visited the ghost towns surrounding the Fukushima nuclear power plant as the guest of Akira Sato, a pastor who was forced to abandon his home and church because of radiation. From him and other eyewitnesses I heard stories of fear and loss.

After spending two nights hunkered down in their earthquake-damaged homes, residents near the Fukushima power plant heard a piercing siren on March 13, 2011. Police cruised through the streets, announcing through bullhorns that everyone had 45 minutes to leave their homes. “Take nothing with you!” the warnings said. “Everything is contaminated!” In a matter of hours, a hastily assembled convoy of buses and other vehicles evacuated everyone who lived within a distance of 12 miles of the power plant, a total of 164,865 people.

Now, seven years later, I entered towns devoid of human habitation. The silence struck me first. I heard no cars, no children playing, no TVs or radios, none of the background static of modern civilization—only the rustling fabric of our hazmat suits as we walked along the empty streets. The scene reminded me of an apocalypse movie. Supermarkets were stocked with goods, though the earthquake had tumbled some products to the floor. New cars lined the lot of a car dealer, waiting for buyers who would never come. A brand-new hospital stood vacant behind a police barrier, with weeds growing up through its sidewalks.

“The first few years, cows and horses wandered through the streets,” Pastor Sato said as we stared at the eerie sight. “We thought the evacuation was temporary, and so neighbors left their dogs chained in their yards. They starved to death. After a while, wild goats, raccoons, and pigs broke into some of the shops and ate the food they found. For a long time we residents weren’t allowed back in. Now I have permission to visit my church, and my home, though I can’t touch or remove anything.”

Leading our little group through his kitchen, Sato pointed to a carton of orange juice on the counter, its contents desiccated, and to a shriveled black banana. Droppings on the floor showed that here, too, animals had roamed in search of food. His collection of books lay strewn on the living room floor where they had fallen after the quake, and he drew my attention to one of mine that had been translated into Japanese. The pastor paused at his daughter’s bedroom, and worked to control his voice. “I’ve visited here many times, but authorities won’t allow anyone in the town under the age of 15. My daughter was eight when we evacuated, and she returned for the first time two weeks ago. She stood in her room, looked at all her clothes, her belongings, the toys and stuffed animals of her childhood, and couldn’t stop crying. My wife could hardly breathe, her heart was so heavy.”

Each time we entered a building we had to slip on a new pair of plastic booties, only to discard them in a contamination bag as we exited. When we toured Pastor Sato’s church—“Our new, undamaged sanctuary, built to last a hundred years,” he said with a wry smile—he shook his head at the equipment left behind: a copy machine, computers, a sound system. In a separate building, an ossuary contained the bones and ashes of church members who had died, along with photos and mementoes of the departed. “We Japanese honor our ancestors, and it was excruciating for us to leave these behind.”

Meanwhile, one of Sato’s assistants had been monitoring a portable Geiger counter to measure the microsieverts of radiation. “Tokyo has an average of .05 mSv,” he said, pointing his probe at a carpet, then a wall, then a planter outside. With a rapid clicking sound the gauge spiked up to a high of 8.5. “Don’t worry. During the meltdown, it measured 125.” I tried to feel reassured.

After the evacuation, Pastor Sato’s congregation scattered across Japan. Like all Fukushima survivors, they faced discrimination and shunning from people afraid of contamination. Restaurants refused service, and even some hospitals declined to treat them. “Elderly patients were abandoned for three days in the hospital you saw over there, and some of them died while being evacuated,” Sato said. “We felt like pariahs. I was a shepherd with no sheep. Finally, a core group of 30 of us found shelter in a camp west of Tokyo owned by a German mission. We stayed there two years, welcome and safe at last.”

Setting aside their fears, Sato and his little flock ultimately decided to relocate to a small city just outside the forbidden zone and plant a new church. “As you know,” he said, “there aren’t many Christians in Japan. We make up only 1 percent of the population. We didn’t want to arouse suspicion, so first we built housing for senior citizens, and opened a clinic. We gained the city’s trust, and now we have a new church building. Our little group of 30 has grown to 100. I’m proud of the way the tiny churches in this area responded to the tragedies. They operated feeding stations, and offered refuge to those without homes. Soon crews from Samaritan’s Purse and other organizations came from the US and Europe to build new houses to replace those destroyed in the tsunami. God is at work in Japan!”

I spoke at Pastor Sato’s new church, as well as several others in the region devastated by the tsunami. “You’ve written books on pain and suffering,” my hosts said. “Teach us what you’ve learned.” As I listened to the stories from survivors who lost their homes and relatives, I felt utterly unqualified. They should be teaching me.

Japan is nothing if not resilient. Who can forget the long lines of survivors patiently waiting for a bowl of rice and cup of water after the tsunami? Even today, thousands still live in temporary housing, and the ones I interviewed spoke of their gratitude for the outside help, with no trace of anger at the disruption to their lives. I saw crews constructing a huge concrete barrier offshore to protect against another tsunami, and drove through entire towns and villages that have been rebuilt. The Japanese people show a remarkable fortitude learned through a history of catastrophes.

Nagasaki

In the past seventy-five years Japan has endured war, earthquakes, floods, fires, tsunamis, nuclear meltdowns—and the only two atomic bombs used in conflict. After visiting Fukushima I flew to Nagasaki, the target of one of those bombs. Here, nuclear power was intentionally released in a blast that killed 40,000 instantly and far more in the ensuing months due to radiation poisoning.

As I toured the museum that depicts the unimaginable horror of that day, I found myself wishing that world leaders who are ramping up their nuclear arsenals and trading threats about the size of nuclear buttons and “invincible weapons” would visit the museum in person and see with their own eyes the apocalyptic consequences of weapons they discuss so cavalierly.

Yet even here Japan’s resilience was on full display. Apart from a memorial park marking ground zero in the center of town, you would never know that this modern city was once a barren, toxic wasteland.

I spent the next several days in Nagasaki with a different agenda, however: to follow the ancient trail of the “Hidden Christians.” In 1597 the despotic Japanese warlord Toyotomi decided to purge Japan of all believers in what he considered a foreign religion. He selected 26 representative Christians and force-marched them in the winter some 500 miles to Nagasaki, the port city where the faith was flourishing. The group comprised three Jesuits, six Franciscans, a Mexican missionary, and 16 Japanese laymen, including three young boys. There, before a large crowd, he had all 26 crucified.

“The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church,” wrote the ancient theologian Tertullian. In Japan, it was almost the annihilation of the church. Shoguns proceeded to outlaw Christianity, requiring Japanese to renounce the faith at least once a year by stepping on the fumie, a bronze plaque depicting Jesus. Those who resisted, they killed by a variety of torturous means. Some they pushed off cliffs, others they beheaded, or crucified in the ocean to be drowned by rising tides, or burned alive in bamboo mats. The most recalcitrant, they hung upside down over a pit, their ears slit so that the slow drip of blood would lead to an agonizing death. In one mass execution, a shogun’s troops slaughtered 37,000 Christians huddled inside a fortress.

Initially, Japan had been a fertile mission field, with as many as 300,000 Christians worshiping in 250 churches. After nearly three centuries of brutal persecution, it appeared that the religion had vanished from the nation, a forgotten footnote of history. Eager to join the modern era, Japan agreed to allow freedom of religion—for foreign residents only—in 1865. That year, an astonishing scene played out in a newly built Catholic church. A ragtag group of villagers from a remote island showed up among the foreigners and whispered to the priest, “All of us have the same heart as you.” Taken aback, the local authorities exiled and punished these Japanese believers, prompting an international outcry that would eventually persuade the government to repeal the ban on Christianity.

Embarrassed by this legacy of cruelty, Japan officially ignored the existence of the Hidden Christians until 1966, when Shusaku Endo published his classic book Silence, a historical novel set in the shoguns’ era of intense persecution. More recently, in 2016 Martin Scorsese released a big-budget movie based on the novel, which drew further attention to the heroic saga of these beleaguered believers. Although the movie had a modest reception in the US, it attracted large crowds in some Asian countries. Soon groups of Korean Christians began making a pilgrimage to Japan to honor those who had suffered for their faith. And now Japan has applied for World Heritage status for the historical sites related to Hidden Christians.

Today, in addition to Korean pilgrims, tourists arrive on cruise ships from China and other countries, many of them encountering the potency of the Gospel for the first time. They stand before the Martyrs Memorial and gaze at life-size bronze replicas of the 26 who were publicly crucified. They see a prison where 200 Christians were squeezed into a room large enough for only 12 sleeping mats and kept for eight months, with 42 of them dying in the process. They visit churches on outlying islands built by missionaries after the Hidden Christians regained the freedom to worship openly.

I visited these sites and many others. I read the plaque on a “torture stone” where a 22-year-old woman was stripped to the waist and forced to squat on a rock in the middle of winter for seven days until she fell unconscious into the snow. (After being revived, she was exiled, but returned to found an orphanage, where she served the church for 68 years.) I spent an afternoon in the stunning Shusaku Endo museum, built on a cliff from which Christians had been tossed into the sea. I climbed trails to see the remains of stone walls that mark huts where Hidden Christians had lived deep in the forest, clinging to a faith that carried with it a death sentence. There, our guide pointed out a praying rock, the one place Christians could pray aloud without fear of being overheard. The era of silence has now ended, and faith itself has proved courageously resilient.

The central drama of Scorsese’s film, like Endo’s novel, hinges on the moral dilemma faced by Jesuit priests sent from Portugal to minister to the Japanese. In one museum, a guide—himself a descendant of Hidden Christians—translated for me an authentic 17th-century signboard promising 500 pieces of silver to anyone who turned in a priest. Once captured, the priest was tied up and forced to watch as groups of Christians were paraded before him. If he stepped on the fumie to apostatize, he was set free. If he refused, the Japanese believers were sacrificed before his eyes. In Endo’s words, “He had come to this country to lay down his life for other men, but instead of that the Japanese were laying down their lives one by one for him.”

I returned from Japan in the midst of the Lenten season, haunted by the scenes of suffering. And in the stack of mail waiting for me, I found the “World Watch List 2018” published by Open Doors, listing the 50 countries where it’s most dangerous to follow Jesus today. North Korea, Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Pakistan head the list of places where simply admitting to be a Jesus-follower risks death.

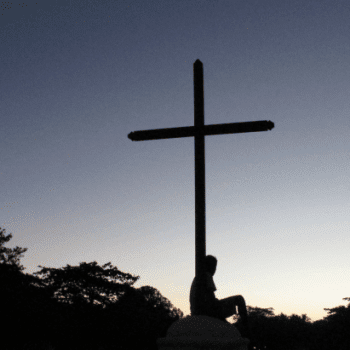

As Good Friday approached, I could not help wondering about a particular kind of suffering that Jesus must have borne, one seldom mentioned in reflections on that day. What must it have been like for him, knowing as he must that the faith he was setting loose on the world would result in the persecution and martyrdom of so many throughout history, including so many Japanese? “Brother will betray brother to death, and a father his child,” he had predicted; “Everyone will hate you because of me, but the one who stands firm to the end will be saved.”

Osaka

On my last stop in Japan, I spoke to a gathering of Christians in Osaka, Japan’s third largest city. Skyscrapers surround a large park dominated by the eight-story castle built by Hideyoshi Toyotomi, the warlord who first ordered the extermination of Christians. I arrived several weeks before the flowering of Japan’s famous cherry trees, which encircle the castle. Plum trees, though, were bursting into bloom.

I stood amidst an orchard of 1,270 plum trees, staring up at the gilded castle from which Toyotomi had issued his decree. Gnarled, blackened trunks that had stood bare through the winter, like dead sticks, were now erupting in bright colors, a harbinger of springtime’s fullness mere weeks away. Nature, like humanity, shows strong resilience, a clue to the deep pattern of the universe.

Easter Sunday is just around the corner. On this day, though, a day called Good Friday, I cannot stop thinking about the cost it takes to get there—for Jesus as well as for many of his followers.

“All these people were still living by faith when they died,” Hebrews 11 says about others who suffered for their faith. “They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth.… Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them.”

Philip Yancey is an award-winning Christian author, whose books include Disappointment with God, Where is God When it Hurts?, The Jesus I Never Knew, What’s So Amazing About Grace?, and Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference?