by Philip Yancey

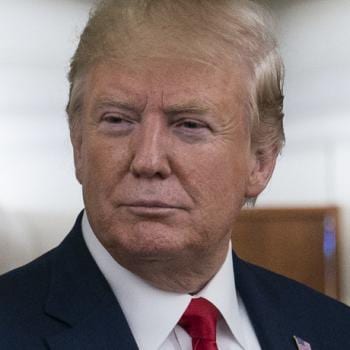

In its Person of the Year cover story, Time magazine gave Donald Trump the title “President of the Divided States of America.” With good reason. A glance at the electoral map shows solid blue on the west and northeast coasts and, in between, a huge swath of red extending across all but four states. Although Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by a healthy margin, Trump won 2,623 counties to Clinton’s 489. The modern United States pits the coasts against the middle, urban areas against all the rest.

The division cuts across religious lines as well. More people who claim no religious affiliation—the “nones”—voted this year than ever before, two-thirds of them opting for Clinton. In contrast, 81 percent of white evangelicals supported Trump, more than voted for Bush, McCain, or Romney. Yet almost the same percentage of African-American and Hispanic evangelicals voted against Trump. Our “one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all” is showing fault lines.

Society’s tainted perception of evangelicals especially grieves me. As a writer, for four decades I have lived within that world. They are my tribe, my community of faith. I wrote a column for Christianity Today magazine, a mainstream evangelical publication, for thirty-six years. Now the word has such a negative connotation that Fuller Seminary has publicly repented for whatever they’ve contributed to shame and abuse by using the word evangelical.

Prominent evangelicals such as James Dobson, Anne Graham Lotz, Jerry Falwell Jr., and Eric Metaxas heartily endorsed Trump, some of them calling his unforeseen victory “a direct intervention by God.” Others, including well-known author Max Lucado and the Southern Baptist executive Russell Moore, demurred. The man whom Moore replaced, Richard Land, quipped that Trump was his eighteenth choice of seventeen Republican candidates; like a lot of voters, he held his nose and supported him anyway.

I got a taste of the strong feelings about this election when I gave an interview to a journalist in Spain last September. We discussed the paradox of American evangelicals’ support for a billionaire who makes his money from casinos, offends women and minorities, and boasts about his extramarital conquests. I admitted that I, too, was baffled. I could understand why an evangelical Christian would vote for Trump on the basis of key issues, like abortion. But to make him a hero, a standard-bearer for Christians? I had no explanation.

Of all the words I’ve written and spoken over the years, only those have gone viral on the Internet. Responses on my FaceBook site increased by a thousand percent, which landed me on FaceBook’s Top Ten Trending list for four consecutive days, just under Brad and Angelina’s divorce. Over the next week I read through hundreds of comments, some of which labeled me a traitor, a pinko communist, a sodomy-loving, baby-killing Muslim who denies our Savior—all because I questioned Mr. Trump’s reputability.

And now, in a matter of days, he will take the oath of office. Trump supporters are jubilant that a brash outsider has arrived to “drain the swamp” in Washington. Meanwhile, his opposers actively fear his policies and world leaders are holding their collective breath. Donald Trump is our President, and those of us who follow Jesus have some repair work to do in helping to heal our nation.

Three Big Losers

I begin with a warning to fellow-evangelicals. We dare not gloss over the damage inflicted by last year’s presidential campaign. Donald Trump likes the word loser: a Twitter archivist has counted 170 times in which Trump called someone a loser in a Tweet. I see three big losers as a sour legacy of the 2016 election.

First, civility lost. I must fault Trump especially for debasing the presidential campaign. He had a pejorative nickname for almost everyone: Crooked Hillary, Crazy Bernie, Low-Energy Jeb, Lyin’ Ted, Little Marco. In the three presidential debates, Trump interrupted Clinton almost one hundred times. He bullied people offstage and on, mocking a disabled reporter, disparaging women for their looks or their weight, playing to racist fears and ethnic prejudice. Bullying, racism, sexism, and xenophobia have always been present in American society, but never before has a candidate for the presidency modeled them so blatantly. Trump let the bats out of the cave, in effect legitimizing the darkest side of a free society. When he won, a devout Christian friend sent out an email with a headline referring to Hillary Clinton, “Ding, dong, the witch is dead!”—I cannot imagine her saying that before the Trump campaign.

Second, religion lost. Robert Putnam’s book American Grace ties the rise of the non-religious, or “nones,” to a reaction against the entanglement of religion and politics. They view Christians as a Moral Majority trying to impose their values on everyone else, and in the process they miss the core gospel message of God’s extravagant love for sinners. The word evangelical means “good news,” and I think of the many disciplined, selfless people around the world who care for the needy and the suffering and who gather together to worship a God who wants us to thrive in this world. When the media use the word, however, they have in mind an uptight political lobbying group, mostly white, mostly male, and overwhelmingly Republican. The good-news tone gets lost in partisan acrimony. Shane Claiborne said it well: “Mixing Christianity with a political party is like mixing ice cream with horse manure. It might not harm the manure, but it sure messes up the ice cream.”

Perhaps most importantly, truth took a hit. As if in acknowledgment, the Oxford Dictionaries named post-truth as their Word of the Year 2016; facts took a back seat to appeals to emotion. When I ask friends why they support Donald Trump, I hear the common response, “He tells it like it is.” If only. I opposed the Iraq war from the beginning; I never mocked a disabled reporter; the NFL sent a letter asking me to reschedule the debate; thousands of Muslims celebrated in the streets of New York after 9/11; nobody has more respect for women than I do; millions fraudulently voted for Hillary—all these claims by Trump were provably false, yet not one hurt him in the polls. Truth didn’t matter.

At the same time, Clinton opponents pounced on her dissembling about email servers, her cover-up of speeches to Wall Street, and the shady dealings of the Clinton Foundation. Add in the fog caused by fake news stories—many of them concocted in Macedonia, it turns out—and truth emerges as the biggest loser of all.

Sebastian Mallaby, a British reporter from the Economist, described how post-truth distorts reality. Both the Clinton and Trump campaigns played on fears of the future. Where is the country’s infectious optimism that won me over as a young journalist? asked Mallaby. From campaign rhetoric, you’d never guess the facts: during the past decade, abortion, crime, immigration, and unemployment have all declined. Mallaby urged, “Do not talk the United States into a self-feeding depression.…If Americans can’t fix all their problems, can they at least rediscover their old talent for living cheerfully with them?”

President-elect Trump has backed away from many of his most controversial campaign promises. He has softened his pronouncements on such matters as jailing Hillary Clinton, mass deportations, military use of torture, climate change, nuclear proliferation, banning all Muslims, abortion, and Obamacare mandates. What message does this give future politicians? That truth doesn’t matter? That you can promise anything to get elected and then immediately pivot, even before you take office?

That kind of Newspeak makes me leery of trusting what Donald Trump says. After dismissing The New York Times as the scum of the earth during the campaign, President-elect Trump met with reporters and declared the paper “a great, great American jewel.” He once referred to Ronald Reagan as a “con man”; now he’s the president Trump most admires. After dismissing Bill Clinton’s sexual escapades as “totally unimportant,” he flipped, labeling him as “the worst abuser of women in the history of politics.”

Many evangelicals and Catholics named abortion as the deciding issue in their vote. But what is Trump’s position on abortion? The one in which he said women should be punished for having an abortion, or the one in which he supported Planned Parenthood and said his liberal sister, a pro-choice judge who ruled against restrictions on partial-birth abortions, would make a “phenomenal” Supreme Court justice?

According to exit polls, voters mistrusted Hillary Clinton as well, and she too flipped positions during the campaign. Making political decisions in a post-truth world gets tricky.

Resident Aliens

In the London subway system, as a train pulls up you hear the recorded announcement, “Mind the gap!” In other words, pay attention to the gap between the platform and the train lest you fall. I glance again at the electoral map, blue on the margins, predominantly red in the middle. A nation so divided is not a healthy nation. We need to mind the huge gap that risks making our nation divisible.

After their loss, Democrats are doing some soul-searching. Caught completely off guard, they are studying books like J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy in an attempt to fathom where all those angry voters came from on election day, whereas their polls showed candidate Clinton with a comfortable lead. Those who live on the coasts assumed that their “enlightened” ideas about tolerance, gender, political correctness, immigration, recreational drugs, abortion, and assisted suicide would gain acceptance in Middle America. They were wrong. Vance’s book shows how government policies in Appalachia did nothing to stop—and may even have abetted—poverty, unemployment, family breakdown, drug abuse, and a culture of violence.

Ross Douthat, a Catholic and a conservative voice on the New York Times op-ed page, has this advice, which he doubts will be taken:

Democrats could attempt to declare a culture-war truce, consolidating the gains of the Obama era while disavowing attempts to regulate institutions and communities that don’t follow the current social-liberal line. That would mean no more fines for Catholic charities and hospitals, no more transgender-bathroom directives handed down from the White House to local schools, and restraint rather than ruthlessness in future debates over funding and accreditation for conservative religious schools. Without backing away from their support for same-sex marriage and legal abortion, leading Democratic politicians could talk more favorably about moral and religious pluralism, and offer reassurances to people who feel themselves to be dissenters from a very novel cultural regime.

I am old enough to remember when both political parties tolerated divergent views. In 1972 Senator George McGovern selected a prominent anti-abortion spokesman, Senator Thomas Eagleton, as his running mate. (Eagleton later resigned in the wake of revelations about his treatment for depression, and was replaced by Sargent Shriver.) On the other side of the aisle, the Republican Mark Hatfield was one of few who consistently opposed the Vietnam War; he joined McGovern in sponsoring a bill calling for a complete withdrawal of troops.

Today, both parties push toward the extremes, in opposite directions. And here is where Christians come in. Oddly enough, we can mind the gap by withholding complete loyalty from either party. “Politics is the church’s worst problem,” warned the French sociologist Jacques Ellul. “It is her constant temptation, the occasion of her greatest disasters, the trap continually set for her by the prince of this world.” Christians have a divided loyalty, committed to helping our society thrive while giving ultimate loyalty to the kingdom of God.

We are resident aliens, taking guidance not from a party platform but from the life Jesus modeled for us. Sometimes that means crossing the gap, rather than widening it.

In a sermon to New York’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church, Tim Keller set forth eight characteristics of early Christians, who lived under a Roman government far less congenial to Christianity than is the modern United States. They followed the following principles:

- Opposed bloodthirsty sports and violent entertainment, such as gladiator games

- Opposed serving in the military

- Opposed abortion and infanticide

- Empowered women

- Opposed sex outside of marriage and homosexual activity (pederasty was common in the empire)

- Encouraged radical support for the poor

- Encouraged the mixing of races and classes

- Insisted that Jesus is the only way to salvation

Go back over that list and apply the label liberal or conservative. Half of the principles reflect traditionally conservative values, and half traditionally liberal—precisely Keller’s point. Though some of the cultural issues may change over time, always Christians have a dual allegiance, to an earthly society and also to what Hebrews 11 calls “a city with foundations, whose architect and builder is God.” That chapter in Hebrews honors heroes and heroines who stepped out in faith against societal norms, and paid a severe price for doing so. “And they admitted that they were aliens and strangers on earth,” Hebrews adds. “They were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them.”

The early church formed pioneer settlements that showed their society a different way to live. When Roman citizens abandoned their unwanted babies to wild animals or the ravages of weather, Christians organized platoons of wet nurses and adoptive families. When plague broke out and villagers fled, the Christians stayed behind to care not only for their relatives but also for their pagan neighbors. They quietly demonstrated a better way to live, the way they believed Jesus had taught. Today, a cross tops the very Roman Colosseum that once showcased violent games and saw the deaths of many Christians. Against all odds, the Jesus way triumphed.

Many Americans shake their heads over the choice that confronted us in the election of 2016. Remember, the earliest Christians had no choice, and lived out their faith under the likes of Nero and Caligula. The trend continues: the greatest numerical revival in history has taken place in recent times under a regime harshly opposed to the Christian faith, Communist China. Christians should take heart that no hostile government can squelch the faith, while also heeding Jacques Ellul’s warning that our hopes do not depend on our access to secular power. Ellul wrote those words from Europe, a region that largely abandoned the faith because church and state had grown too cozy, too entangled.

Bridging the Gap

Because of our dual loyalty, Christians have an important role to play in bringing reconciliation and healing. After the election I received an email from a pastor in Chicago who, like many urban pastors, was shocked by the results.

“Being a Christian is hard,” she began:

Throughout the last few days I have thought about how much easier it is for me to be a “left of center leaning progressive” than it is for me to be a Christian. As a political party member I can vent and debate, mock and obfuscate other’s policies. As a Christian I must lean in and listen; I must embrace and include.

While the political part of me seeks revenge, (“Let the markets crash! Watch Putin’s advances with a weakened NATO! See the dismantling of America’s leadership!”) the Christian in me must pray for the welfare of the city, our country and the world. The claims of Christ demand that I seek the things that make for peace.

I can’t mock those who voted for Trump or suggest that the rise of the “know nothing” party is complete. I don’t get to paint them with a wide brush of ugly words. And perhaps most temptingly, I can’t try and write off the “other” Christians who supported President-elect Trump. That’s not allowed. Like me, they are beggars of grace. And the One from whose hand we have equally received will not allow me to stand close while my heart is far away.

She concluded, “God is still redeeming the world and asking us to participate. Please join us in praying for our country. Pray for people of color first, along with undocumented workers and those particularly dependent on governmental services and assistance. Pray for the losers and the winners. Pray for people of good will to reach out to their neighbors and friends. Pray that we may find a way forward for all of us together. Pray that the character of Christ will also be the character of his people.”

If Hillary Clinton had won, I would hope that conservative Christians would have responded in like spirit. We follow, after all, a leader who commanded us to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. Politics is an adversary sport: it divides and labels, and demeans its opponents. Bottom line, politics is about winning. The Christian has a different bottom line: love. For this reason, I hope that evangelicals will lead the way in standing up for marginalized groups and minorities who feel genuine fear, even as we pray for the new administration taking office.

At times, Christians must enter the political fray, especially in a democracy that guarantees our right to do so. Some of the issues facing our nation are moral issues that require our activism. In a post-truth era, we still believe Truth matters. Yet, as Martin Luther King Jr. used to say, the Christian wields different weapons in political conflict, the weapons of grace.

King provides a sterling example. David Chappell’s book, A Stone of Hope, shows that for decades liberal humanists made no progress in overturning segregation laws. They assumed that education and their “enlightened” views would gradually change the minds and hearts of racist Southerners. I grew up as a racist Southerner under segregation, and I know well that it took more than contagious enlightenment to change me and those around me. It took direct action, led mostly by prophetic clergy like King, who fought with different weapons.

King understood his ultimate loyalty. His real goal, he said, was not to defeat the whites but “to awaken a sense of shame within the oppressor and challenge his false sense of superiority.…The end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the beloved community.” That is what Martin Luther King Jr. set into motion, even in diehard racists like me. The power of grace disarmed my own stubborn evil.

As I wrote in my book Soul Survivor, “In the end, it was not King’s humanitarianism that got through to me, nor his Gandhian example of nonviolent resistance, nor his personal sacrifices, inspiring as those may be. It was his grounding in the Christian gospel that finally made me conscious of the beam in my eye and forced me to attend to the message he was proclaiming. Because he kept quoting Jesus, eventually I had to listen. The church may not always get it right—and it may take centuries or even millennia for its eyes to open—but when it does, God’s own love and forgiveness flow down like a stream of living water.”

Other scenes come to mind. Devout Filipinos kneeling before fifty-ton tanks, which lurched to a halt as if they had collided with an invisible shield of prayer. Nelson Mandela emerging from twenty-seven years in prison to plead against revenge, and entrusting the reconciliation process to Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The prayer meetings in Leipzig, Germany, growing into candlelight processions by a few hundred, then a thousand, and finally 500,000 hymn-singing marchers; the marches spreading to East Berlin, where a million walked through the streets until the ugly Berlin Wall came tumbling down without a shot being fired.

Closer to home, I think of Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, an evangelical who spoke out against sexual promiscuity—consistently he used the word “sodomy” when referring to homosexual acts—and yet became a hero to the gay community by forcing Republican administrations to devote massive resources to address the AIDS crisis. Why? As a physician, he spent time among the early AIDS sufferers. “How can you not put your arm around that kind of person and offer support?” he said. His Christian compassion trumped all else.

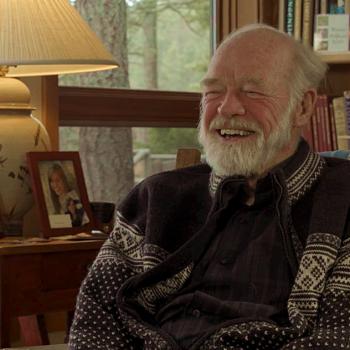

Some historians trace evangelicals’ involvement in politics back to Koop and his mentor Francis Schaeffer, who together toured the nation urging evangelicals to become active in abortion and end-of-life issues. I once asked Schaeffer which of his dozens of books gave him most satisfaction. He thought for a moment, no doubt mentally scanning the major works of theology and culture, and settled on a 35-page booklet often overlooked, The Mark of the Christian. Schaeffer considered it so important that he added the essay as an appendix to the last book he wrote, The Great Evangelical Disaster.

Toward the end of his life, as he saw the word evangelical become synonymous with political lobbying, Schaeffer sometimes wondered what he had helped set loose. He based The Mark of the Christian on some of Jesus’ last words to his disciples: “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.”

Schaeffer added, “Love—and the unity it attests to—is the mark Christ gave Christians to wear before the world. Only with this mark may the world know that Christians are indeed Christians and that Jesus was sent by the Father.…It is possible to be a Christian without showing the mark, but if we expect non-Christians to know that we are Christians, we must show the mark.” I that see as the biggest challenge facing committed Christians in the new year.

As the dust settles from the storm of 2016, I pray that those of us who follow Jesus remember that mark above all. The apostle Paul used these words to describe the characteristics of a true Christian: humility, charity, joy, peace, gentleness, forbearance, patience, goodness, self-control—words in short supply last election year. Republicans will busy themselves with the difficult task of governing a factious nation in a perilous world. Democrats will huddle to devise a new playbook. May Christians of all persuasions remember that our ultimate allegiance and our ultimate hope belong to neither party. As resident aliens in a divided nation, may we too form pioneer settlements to show the world the Jesus way.

Philip Yancey is an award-winning Christian author, whose books include Disappointment with God, Where is God When it Hurts?, The Jesus I Never Knew, What’s So Amazing About Grace?, and Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference?