There have been several excellent books in the genre “A year of” doing this or that: A. J. Jacobs’ The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possibleand Rachel Held Evans’ A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband Master

immediately come to mind.

If I were to write a book of this sort, I think it would be The Year of Living Justly, and it would focus on my attempt to disentangle myself from every form of injustice that my shopping habits help perpetuate.

This blog entry is not about how I am going to write such a book, but about why I almost certainly won’t – or can’t.

The problem, in a nutshell, is this: I can’t figure out how to disentangle myself from injustice.

I had the idea for a book of this sort as I pondered the contradiction inherent in what I was about to do on a recent trip to do some grocery shopping, namely purchase some fair trade coffee…at Wal-Mart.

Many might try to address the issue by saying, “Don’t shop at Wal-Mart” – at least not until its workers are paid a living wage that does not have to be subsidized by food stamps in order for them to be able to make ends meet.

But plenty of other stores have not done significantly better than Wal-Mart, and so it isn’t clear that simply choosing another retailer is going to help.

And even if I found a store that I could be certain pays its employees fairly in which to shop for groceries, I would still have to navigate the products. Some bear the fair trade label, but do I really know whether the people involved in producing the plant and processing it are paid and treated fairly?

And even if I found a store that I could be certain pays its employees fairly in which to shop for groceries, I would still have to navigate the products. Some bear the fair trade label, but do I really know whether the people involved in producing the plant and processing it are paid and treated fairly?

And what about all the other products? Shall I walk into ALDI with a notepad, write down all the company names, and contact each one to ask whether children who should be in school picked those vegetables? Do I have a way of determining whether the answer they gave me on the phone, if I were to call them up, would be honest?

I would love to live justly, in the sense of disentangling myself from injustice, and to do so not only for a year. But I scarcely know where to begin.

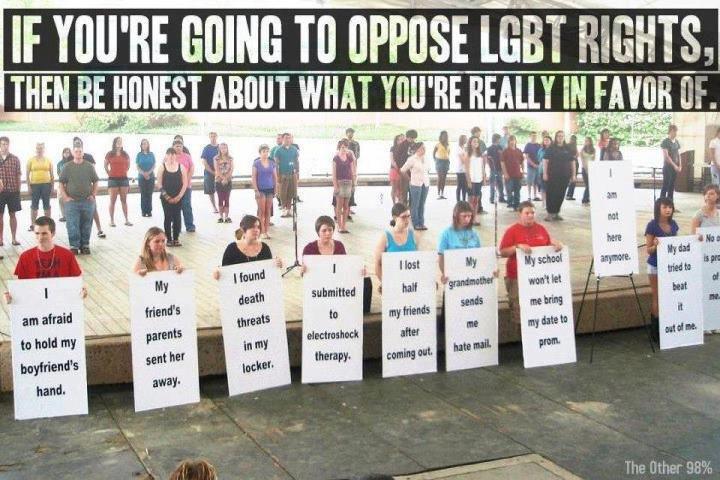

And what about Chick-fil-A? If I buy those delicious waffle fries, am I contributing to discrimination against gays and lesbians? If I choose not to, am I harming a local business owner who is just trying to make ends meet while doing nothing to change where 91-year-old Truett Cathy gives his money?

In other words, are both actions unjust to some extent, and if so, then how do I decide which is the greater injustice? But even if I manage to choose the smaller one, I have still not disentangled myself from injustice.

In other words, are both actions unjust to some extent, and if so, then how do I decide which is the greater injustice? But even if I manage to choose the smaller one, I have still not disentangled myself from injustice.

The other question that troubles me is one that troubles us all when we contemplate action on the individual level to try to make a positive difference in the world: Even if I were to carry out this enormous task, how much difference would it make, if I and no one else made this effort?

This is where the subject of this post intersects most directly with a topic I’ve been discussing a lot lately here on this blog and on Facebook, as have others around the country. If we want to hold businesses accountable and demand that their payment and treatment of workers is fair and just, it is only as a community that we can do this. This is why liberals like myself are persuaded that there has to be a communal – and in the United States, this naturally means governmental – component to solutions to problems of economic and social justice. Customers can write letters on their own, or we can take our business elsewhere. But in our democracy we can also band together through the government that represents us, and demand things be expressed through law and overseen by government organizations, such as that food be inspected for safety, that a living minimum wage be paid, and pretty much everything else that has to do with ensuring that the freedom of the wealthy and of businesses does not ride roughshod over the freedom of the less wealthy and less powerful – assuming that we can agree that the right to eat without fear of being poisoned, or the right to be paid enough to live on for one’s labor, are rights that everyone should have in a society which emphasizes “liberty and justice for all.” But it is agreeing on that which seems to be precisely what the population of the United States cannot do at the moment.

And so key questions remain, concerning how we go about consensus-building, and why so many Americans think that their own freedom from paying taxes to support such concerns is more important than addressing the profound injustices and inequalities in our society, as other democratic and prosperous nations have done to a much greater extent than we have. If neither concern for others nor national pride persuades them, then what will? And to the extent that a given issue is a matter of justice, it is legitimate to ask whether doing something about it should depend on popular opinion, or are there times in which government can rightly insist on implementing the nation’s foundational principles, as happened in the case of slavery, segregation, and many other examples?

In concluding, here’s a nice video about the Chick-fil-A controversy, which addresses the Biblical inconsistency of those who claim to support “Biblical marriage” as well as the most likely reason why Chick-fil-A doesn’t discriminate against employees and customers: because it would be illegal to do so. In other words, government and legislative solutions matter, and they help in at least some circumstances.

The video also has an interesting idea for a protest (planned for August 1) that will test the company’s alleged Biblical principles.

What do readers think? How do we address injustice, individually and corporately? Should someone write a book on living justly for a year, and perhaps give us all some useful pointers? Do you have any advice for those who are concerned to disentangle themselves from social and economic injustice to whatever extent they can?