Even though evolutionary biology is currently getting all the public attention about the relation of science to religion, an exploration of physics and astronomy seems appropriate given Stephen Hawking’s public reemergence with the series “Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking” currently airing on the Discovery Channel. The show is about physical cosmology, the scientific attempt to understand the origin, evolution, and basic structure of the universe. So let’s jump into the science starting with the figure who set cosmology on its modern course.

Even though evolutionary biology is currently getting all the public attention about the relation of science to religion, an exploration of physics and astronomy seems appropriate given Stephen Hawking’s public reemergence with the series “Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking” currently airing on the Discovery Channel. The show is about physical cosmology, the scientific attempt to understand the origin, evolution, and basic structure of the universe. So let’s jump into the science starting with the figure who set cosmology on its modern course.

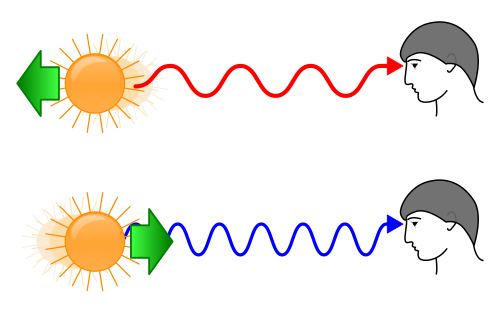

In 1924, Edwin Hubble discovered that nearby galaxies were moving away from the Milky Way Galaxy at a rate that increased the further away those galaxies were from our own. This might make more sense if you think about how raisins move away from each other while baking raisin bread or what would happen if you drew a bunch of dots on a balloon and then inflated it. More importantly, the “redshift” of other galaxies was increasing the further they were from earth. This shift is like the Doppler Effect.

You’ve probably noticed that trains have a different pitch to the sound they make as they approach you compared to once they have passed by. That is because the frequency of sound waves emitted while approaching and moving away is different. The redshift is the same thing, only for light sources, and Hubble was able to detect the redshift of other galaxies. It was becoming clear that space was expanding. This work was further supported by the discovery of uniform background radiation.

You’ve probably noticed that trains have a different pitch to the sound they make as they approach you compared to once they have passed by. That is because the frequency of sound waves emitted while approaching and moving away is different. The redshift is the same thing, only for light sources, and Hubble was able to detect the redshift of other galaxies. It was becoming clear that space was expanding. This work was further supported by the discovery of uniform background radiation.

The temperature of the radiation is remarkably consistent throughout the sky (the differences in color in this picture only amount to 0.1 degrees kelvin or less). Such strong consistency in temperature indicates that the universe was once in a rather homogeneous state in which a massive amount of energy capable of producing such radiation was released.  By extrapolating back in time from these observations, a singular point of infinite density has been posited as the standard scientific explanation. It then “exploded” in the Big Bang and that infinite density was released and developed into the expanding universe we live in today (more about the microphysics in the chart of the Big Bang another week). All of this happened 14 billion, yes with a b, years ago. However, there are problems with this picture.

By extrapolating back in time from these observations, a singular point of infinite density has been posited as the standard scientific explanation. It then “exploded” in the Big Bang and that infinite density was released and developed into the expanding universe we live in today (more about the microphysics in the chart of the Big Bang another week). All of this happened 14 billion, yes with a b, years ago. However, there are problems with this picture.

Planck Time must be used to explain the early moments of the Big Bang. A Planck unit is approximately 5×10-43 seconds in length, a time after the singularity before which scientists have no working model. In other words, the best scientific knowledge currently available cannot get at the actual existence of a singularity, but can only propose it as the best current theory for the start of the Big Bang. This dilemma has led Steven Hawking (his book A Brief History of Time is still a fun and easy to read introduction to cosmology) to pursue the application of quantum mechanics, relativity, and a tentative theory of quantum gravity to explore the possibility of a testable hypothesis for the early conditions of the Big Bang for scientists to work with.

Hawking’s uses a rather hypothetical approach to understanding the early conditions of the Big Bang in which he considers every possible path particles could have taken through space. By calculating the histories of waves passing through all points, he can eliminate those with equal amplitude and consider only the most probable paths. If you don’t follow that last sentence, all you need to know is that any distinction between space and time vanishes in this approach. The end result is a curved four-dimensional space-time that is finite with time contained within, but boundless like a sphere. This theory amounts to a rejection of the idea that the universe began at some point in the past.

The concept of time would have no meaning before it emerged from curved space-time. In other words, a boundless sphere can persist “forever” before expanding via the Big Bang because it persisted when time did not exist. So Hawking’s contribution to the cosmological landscape is a theory in which a temporally finite world can exist forever without a beginning. Odd indeed, but a real possibility with growing evidence in its favor (we will cover the possibility that we are living in a multiverse, but you can read The Cosmic Landscape by Leonard Susskind if you want a preview of that REALLY odd cosmos).

So that does it for our first adventure into science, setting up our discussions later this month about what scientists, philosophers, and theologians are making of this data. Leave comments and let me know if anything is unclear. I’ll do my best to clarify. Even worse, if you are following absolutely nothing, let me know if I need to write more, less, or change the tone of my writing about science in future posts. If the science we cover each month is not understood, then venturing into theological possibilities will be fruitless.