Yesterday, the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies at USC Dornsife ran a forum on nuclear disarmament and deterrence. The University of New Mexico hosted the event at the Student Union Building. And UNM’s religious studies program, of which I am proud to be a part, was one of the sponsors.

The venue made perfect sense. New Mexico is where the “Gadget” prototype of the atomic bomb was created and tested. The state is home to Los Alamos National Labs, which was founded with the sole purpose of creating the bomb. Testing wrecked havoc on New Mexican communities, and the two bombs dropped on Japan killed 150,000 to 246,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The forum involved an impressive array of religious leaders, community organizers, scientists, and politicians. A full list of the participants can be found here. The forum held a private event the day before on Friday, where the thirty-two participants took part in passionate, frank, and earnest discussions about the best way forward to abolishing nuclear weapons.

On Saturday, the participants brought the dialogue to the broader public, sharing their experience of the day before, and leading the conversation even further.

The Picket

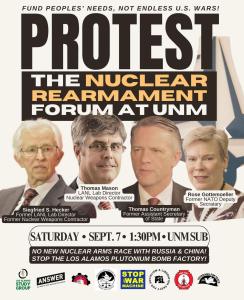

The forum was not without its vocal critics. The Albuquerque Party for Socialism and Liberation, a week before the event took place, called for a protest. The PSL picketed the entrance to the Student Union Building, though they did not block audience members from entering and exiting.

On their call for action, the PSL voiced their concerns with some of the participants. In particular, their post named Siegfried Hecker (former director of Los Alamos National Labs), Thomas Mason (the current director of LANL), Thomas Countryman (former Assistant Secretary of State), and Rose Gottemoeller (former NATO Deputy Secretary, former U.S. Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security).

Mason, according to the PSL, is “overseeing the construction and operation of a nuclear bomb factory . . . , meaning he is playing an active role in building the New Cold War.” As the PSL points out,

New Mexico is where the first atomic bomb was created and tested and to this day is the place where the majority of nuclear weapons components are designed. . . . The largest nuclear waste plant is also in our state.

They add,

As New Mexicans are being driven into poverty and homelessness, the Democrat and Republican parties always find funding for weapons & war in our state, but the [people’s] needs are not prioritized.

The Opening

After receiving literature from some PSL members, I went to check in to the forum. Dr. Kathleen Holscher, chair of Catholic Studies and a professor in Religious Studies and American Studies at UNM, gave the opening remarks. The Archbishop of Santa Fe, Most Reverend John C. Wester, also gave an opening statement, referring to Pope Francis’s condemnation of the very possession of nuclear weapons.

We heard from Most Reverend Joseph Mitsuaki Takami, Archbishop Emeritus of Nagasaki. He was born in Nagasaki, one of two Japanese cities struck by American atomic bombs. When his city was bombed, the future Archbishop was in his mother’s womb. The horrific effects on pregnant women and newborn babies that the bombs wrought is well documented. These effects continue to be suffered by survivors of Nagasaki, Hiroshima, the Marshall Islands, and New Mexico who were targeted by bombings and tests.

Dr. Masao Tomonaga, Vice President of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War also spoke. Like Rev. Takami, Dr. Tomonago is hibakusha, a survivor of the atomic bomb.

The Prayer

Regis Pecos, former governor of Cochiti Pueblo and Co-Founder/Co-Director of the Santa Fe Indian School Leadership Institute gave the benediction for the forum. He prayed to Mother Corn, calling back to those who have come before, honoring those gathered presently. In urgent times like these, Pecos told the crowd, we must honor the core values that Creator and our forebears have gifted us.

In turning from these core values, and in giving themselves to the ideology of supremacy, colonizers have not only created absurdly destructive weaponry to take human life but have also perverted and exploited the earth in order to create, test, and use these devices of death. As Pecos pointed out, the threat of nuclear war is dangerous, but it did not come from nowhere. It is the fruit of this historic transgression of the core values of humanity.

The tragedies suffered at Nagasaki, Pecos said, is the culmination of the “slow death” that we have all been dying because of white supremacy, racism, and coloniality.

Nuclearism and Catholic Social Teaching

As Archbishop Wester pointed out in his opening statement, Pope Francis expressly condemns not only the use, but the possession of nuclear weapons. Cardinal Robert McElroy, Ph.D., Bishop of San Diego and Member of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development developed this even further.

Cardinal McElroy, whose work centers on moral theology and public policy, highlighted the need for nuclear abolition that Catholic social teaching urges the world towards. This teaching is not without development.

Pope Pius XII, on Christmas Day in 1955, delivered an address strongly cautioning the usage and testing of nuclear arms. His successor, Pope John XXIII, called for nuclear abolition. That is, doing away completely with nuclear weapons. He also argued that, according to the Cardinal, the widespread sentiment that possession is justified in order to “deter” enemies from using nuclear weapons against one’s own country must be questioned.

With Pope John Paul II, papal teaching allowed for deterrence, but only as a means towards abolition. This so-called “interim ethic,” the Cardinal declared, no longer holds. Abolition must happen now.

Nuclear Deterrence or Disarmament?

The participants all shared the sense that disarming nuclear states should be humanity’s goal. At this point, and for some time, nations hold the power to end all human life, and perhaps all life on earth.

Dr. Rose Gottemoeller, who was mentioned on the PSL’s call for protest, argued that we have made progress towards disarmament—contrary to what some of the scientists like Dr. Ira Helfand from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons suggested about the government’s intentions.

Dr. Gottemoeller placed chief blame on the leaders of China and Russia. These countries, she said, refuse to negotiate with the US. Until negotiations can continue, disarmament is not prudent. Others, however, argued that there is no time to wait.

Indigenous Communities

But perhaps the most important consideration raised was the Indigenous communities who are most heavily affected by the nuclear age. The atomic bombs dropped in Japan were not invented perfectly the first time. These bombs were forged with the blood and welfare of New Mexicans.

Today, open pit uranium mines remain on Laguna, Acoma, and Navajo lands. Tina Cordova, co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, described vividly the working conditions of the miners. They wore hard hats, gloves, and dust masks. They had to eat their lunch in the mines.

Cordova, in her work with communities, testified to seeing widows and fatherless children on these lands. So many fathers lost their lives mining uranium for the government and its scientists. Her team found that at least 13,000 people lived within a 50-mile radius of the Trinity test site. Within 100 miles, nearly half a million.

The test was an ecological disaster as well. The tests ravaged the soil that New Mexicans used to grow their cops. The ash polluted the waters kept in wells.

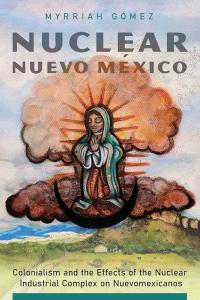

Dr. Myrriah Gómez, UNM Honors College professor and author of Nuclear Nuevo México brings up how over thirty New Mexican families were evicted from their homes and ranches on the Pajarito Plateau in order to make room for nuclear testing. Calling back to something that former governor Pecos had said in his speech, Dr. Gómez pointed to the importance of including Indigenous voices and experiences when talking about the morality of nuclear possession.

Nuclear New Mexico

Indeed, this inclusion is essential. The “Trinity downwinders” have yet to be compensated from the US government. As one Nuevomexicano recounts the aftermath of the Trinity test, “This filth landed all over our town, covered our village with radiation. It was on our roofs, our gardens, milk cows, rabbits, pigs, turkeys, and chickens.”

Had such filth covered the sidewalks of suburbia, or the cities of New York or Chicago, there would be hell to pay.

Cordova brought up a powerful point that stuck with me. New Mexico, per capita, led the US in enlistment, casualties, and bonds during World War II. It was from New Mexico that so many of the now famous Navajo code-talkers came to safeguard American military communications from imperial Japanese intelligence. Yet, despite this immense sacrifice, this land of “Indians and Mexicans” (pre-statehood New Mexico, as Gómez teaches us, suffered from this sort of rhetoric from outlets like The New York Times) bore the brunt of the nuclear age.

Disarmament and the Nuclear Age

The contradiction of the international nuclear age is this. We must, so the world’s governments say, maintain the power to kill everyone, so that someone else won’t do it first. This is the difference between disarmament and deterrence.

The communities who can offer the most in our democratic system today are the New Mexicans who have been affected by the dawn of the nuclear age. However, the effects of what Dr. Gómez calls “nuclear colonialism” continue to oppress and tread on these communities.

Disarmament first requires the alleviation of poverty and disempowerment wrought upon these communities. The nuclear economy has rendered so many peoples and countries financially and politically dependent upon the development of nuclear technology and maintenance of nuclear arsenals.

The broader Church does need to respond. We must take up Catholic Christianity’s insistence upon nuclear disarmament. Not even the Just War doctrine can be defended when humanity can commit what one member of Veterans for Peace calls “vitacide”—the killing of life itself.