From Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Stanley Hauerwas, Christian theologians reject violence as a dogma of Christian social engagement. Indeed, there are several denominations that have enshrined nonviolence (or Christian pacifism) in their distinctives, formally or informally. The Mennonites, the Amish, and other Anabaptist traditions are prime examples of this.

But those familiar with history will know that there have been many Christians (who apologists are likely to euphemize as “people who claimed to be Christian”) who enacted violence in the name of Christ. Those familiar with St. Thomas Aquinas will remember the doctrine of just war, in which violence at the level of the nation is justified given certain conditions. (This doctrine has been called into question at the dawn of the nuclear age; is any war justified when war could mean planetary annihilation?)

Nevertheless, contemporary American Christian theology is for the most part nonviolent. This does not mean that all American Christians are pacifists. In fact violence is justified for most Americans, regardless of religion, when it comes to self-defense. But there is a certain strand of theology which takes this further: Black liberation theology.

What is Black Liberation Theology?

For many, the term “liberation theology” brings to mind that tradition of theology developed in Latin America during the 1960s. Latin American liberation theology was developed by the likes of Gustavo Guttiérez, Hugo Assman, and Leonardo Boff. The task, broadly speaking, of these theologians was to critique the Church, which had become much too aloof from the everyday poverty and suffering of the poor and vulnerable.

Black liberation theology is not exactly derived from its Latin American counterpart. Every type of liberation theology, be it Black, Latin American, Minjung, or Palestinian, is contextual. To say that theology is contextual is to say that, as Duncan Forrester writes,

It addresses itself to a particular situation at a specific time. This is one reason for the diversity of political theologies: since each is rooted in a particular context, they have different agendas and emphases. And despite its concern with the context, political theology is theology i.e. it endeavours to relate the classical Christian theological tradition to a modern situation. Both the classical and contextual are necessary. [1]

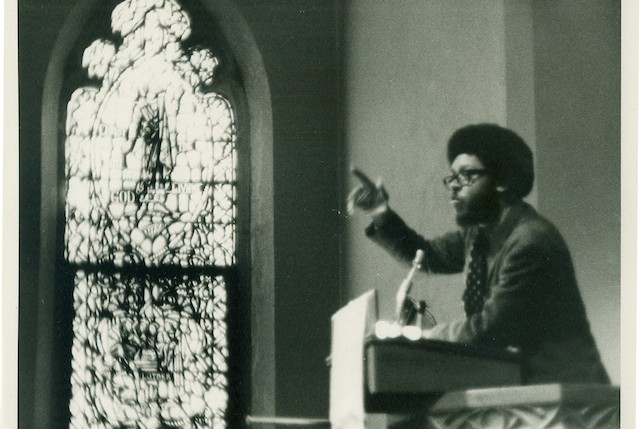

The tradition of Black liberation theology grows from and addresses the concerns of Black people. And James Cone, often regarded as the father of this tradition, articulates these concerns well.

Theology and Black Power

In Black Theology and Black Power, originally published in 1969, Cone connects the practice of Black theology to the Black Power movement. As Dwight N. Hopkins points out, there were two major streams from which Cone’s book sprung. The first was the Civil Rights Movement, which initiated when Rosa Parks refused to sit at the back of the bus for a white man on December 1, 1955. Prominent religious leaders like King directed their work towards protecting rights and the public recognition of the dignity of Black Americans.

The second stream was the Black Power Movement, which began in 1966. In a march with King, a prominent Black activist named Stokely Carmichael called for Black Power. What Carmichael was calling for went further than empowerment. As Cone writes, Black Power is about the “complete emancipation of black people from white oppression by whatever means black people deem necessary.” [2]

Most Americans, I assume, are familiar with the Civil Rights movement. And most are probably apt to see the Civil Rights movement as the end-all-be-all “racial reckoning” that the US needed to wake up from its segregational and racializing slumber.

While the Civil Rights movement made strides towards equality, the need for Black Power as a movement was still necessary. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation and terminated the practice of Jim Crow laws in the South. And the Voting Rights Act in 1965 prohibited numerous practices aimed at keeping Black Americans from voting in Southern states.

However, nations are not changed by legislation alone. For Cone and others in the Black Power movement, Black people were still not seen as “full citizens” due to forms of persecution and disadvantaging less visible from the legislative perspective.

Centering Being

These sub-legislative forces are dehumanizing ones. In the mind of the racist, a Black person is without agency, dignity, and reason. Thus, Black people are racialized as sub- or non-human in a society ran by white supremacy. In response to this, one’s very humanity must be affirmed in a way that “forces white society to look at him, to recognize him, to take his being into account, to admit that he is.” [3]

Another theologian, Paul Tillich, raises an important concept which Cone leverages: the “courage to be.” This courage empowers “man [to affirm] his being in spite of those elements of his existence which conflict with his essential self-affirmation.” [4] This is not a mode of being only for oneself. It is a being that insists that one has a place in society. Furthermore, it is a mode of being that insists upon being recognized.

Cone quotes Franz Fanon: “Man is human only to the extent to which he tries to impose his existence on another in order to be recognized by him.” [5] This act of imposing does not come from a desire to dominate or exclude. It comes from the desire to be recognized.

Is this Politics, Or Theology?

But whither theology? Is Black Power a mere humanism with which theology is “too pure” to deal? In fact, when I discuss forms of radical theology like this one with other Christians, they sometimes interpret these traditions as political rather than both theological and political. As the political theologians remind us, all theology is political.

Cone writes,

While the gospel itself does not change, every generation is confronted with new problems, and the gospel must be brought to bear on them. Thus, the task of theology is to show what the changeless gospel means in each new situation. [6]

Any Christian will recognize that their theology speaks to real and concrete social elements: sexuality, electoral politics, identity, human relations, and forms of rule. But when a strand of theology becomes normal in a community, it sometimes appears to be non-political, even though it still speaks to human life.

A theology only seems all politics and no theology if its concerns (and all theology has concerns) are prejudged to be illegitimate.

Violence in Cone’s Theology

We now turn finally to the role that violence plays in Cone’s theology. Recall that the fundamental concern of Black Power (and therefore Black theology, which speaks directly to the experience and needs of Black people) is the denial of one’s humanity by white power and racism.

When humans are deluded by sin (such as racism), their mind and eyes become clouded. A racist so accustomed to seeing a group of people as inferior, objectified, and in need of being either avoided or subjugated cannot easily see that these people are.

What is needed according to Cone is an affirmation of being. To demand recognition, in Fanon’s term. And this affirmation of being is framed deeply in terms of Christian love. We quote Cone more at length:

Love is the motive or the rationale for action. The attempt of some to measure love exclusively by specific actions, such as nonviolence, is theologically incorrect. Christian love comprises the being of a man whereby he behaves as if God is the essence of his existence. [8]

This conduct is exhibited primarily through loving oneself and loving one’s neighbor, because God is the Creator of all. But when one’s God-created being is ceaselessly denied by another person, Christian love demands that one’s being be re-affirmed, because God defines us all as dignified and human.

The violence in the cities, which appears to contradict Christian love, is nothing but the black man’s attempt to say Yes to his being as defined by God in a world that would make his being into nonbeing. If the riots are the black man’s courage to say Yes to himself as a creature of God, and if in affirming self he affirms Yes to the neighbor, then violence may be the black man’s expression, sometimes the only possible expression, of Christian love to the white oppressor. [9]

Cone’s major critique of nonviolence as an absolute is that so long as Black people remain nonviolent, white racists are free to ignore them. But violence is something that cannot be ignored. And violence is only committed by beings with desires, pursuits, hurts, and dreams. Therefore, for Cone, there are times when violence may be the only means to be recognized by one’s oppressor.

Conclusion

One must keep in mind that one should not initiate violence on Cone’s view. The structures at play which disadvantage and oppress are already violent. Violence as an act of Christian love (whatever the reader may think of that) is not supposed to aim towards domination or getting on top. Nor is violence a means to vengeance, for vengeance is the Lord’s.

Violence, rather, for Cone is a means to recognition. I think back to my years in elementary school. There were times when a bully would barrage and demean another child ceaselessly. No matter if that child attempted to have rational discourse to help the bully see the irrationality of his violence. The bully remained a bully. Not until the child learned how to fight back and defend himself did the bully come to see the child as more than a child-to-bully, but as another person.

Cone is certainly not mainstream in Christian theology. Perhaps this is indicative that most people do not want violence in their lives. However, many forms of violence go unseen or unaddressed in society. Often, those who benefit from this order of violence participate in it to maintain their benefits. The question is not whether violence is the answer in such a situation. The situation already has chosen violence to maintain itself. The question is, will the nonviolence of the oppressed be enough to keep them alive and recognized?

—

For a previous article on violence, see this article on the recent assassination of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione.

References

1. Duncan Forrester, Theology and Politics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988), 150.

2. James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, fiftieth anniversary ed. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2019), 21.

3. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 22.

4. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 22.

5. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 22.

6. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 35.

7. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 35.

8. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 46.

9. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 46.